A migrant family felt ‘blessed’ to be picked for a state rental program. They were given units that seemed unlivable — with a difficult choice.

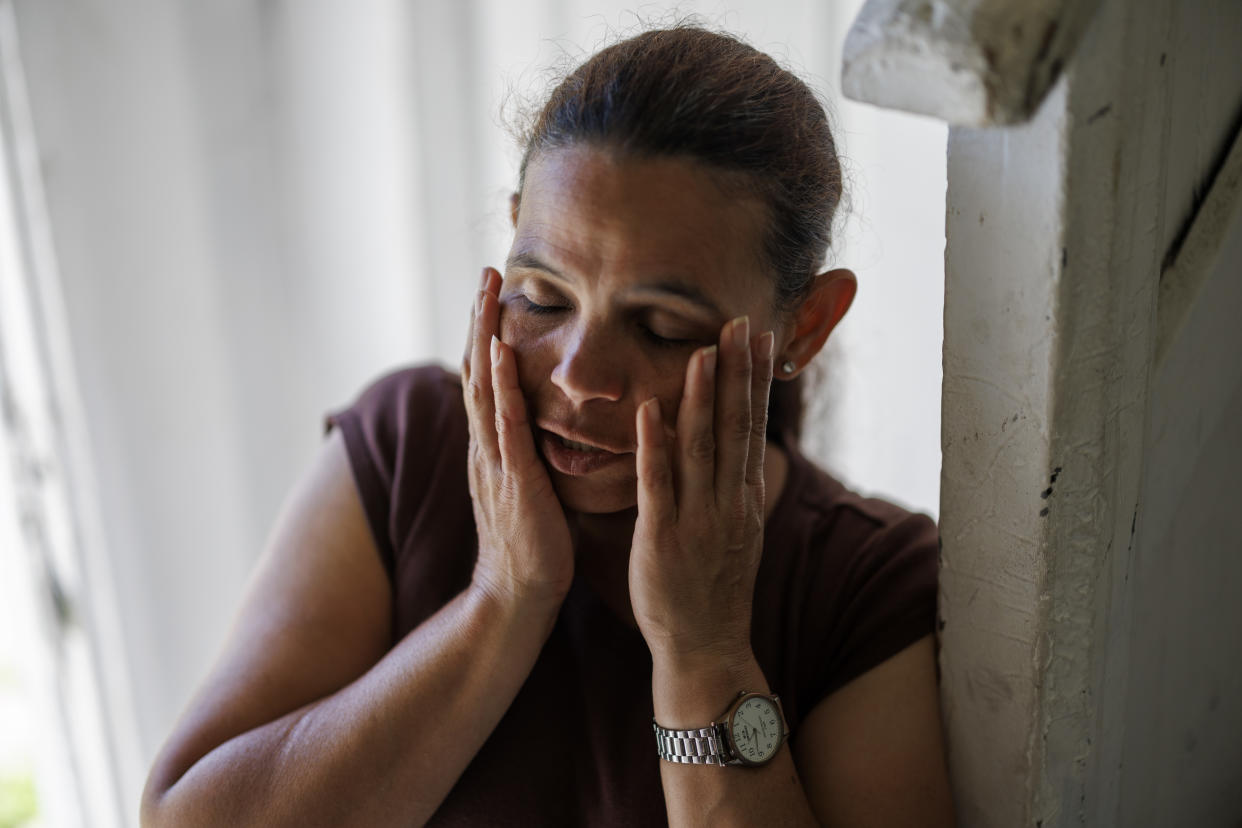

The news last fall couldn’t have come at a better time for Karina Fuentes.

For nearly three months, the 42-year-old Venezuelan migrant had been living in a cramped and musty Streeterville hotel room with her husband and two kids. Space was tight even outside her Inn of Chicago room, with hotel common areas often jammed with hundreds of other migrants from Venezuela, who — like them — had walked roughly 5,000 miles in search of a better life.

Shortly before Thanksgiving, Fuentes got the email she had been hoping for. Her family had been approved for a relatively new state program that promised to help migrants find apartments. The state would cover up to six months of rent — a key move to help the city empty its shelters, which had been swelling with migrants.

The family of four could say goodbye to the Inn of Chicago shelter and take one more step toward the American dream.

“It was a blessing — the property,” Fuentes recalled in Spanish. “My kids, especially, were so happy.”

The family would soon learn, however, of the program’s sluggish bureaucracy and harsh on-the-ground realities. Fuentes, who has both a daughter and husband with serious medical needs, would be offered a series of apartments they considered unlivable. They were among hundreds of migrants whose leases drew scrutiny from the state, with dozens of cases so troubling the state kicked landlords out of the program.

Caseworkers contracted by the state would find themselves at times rushing through paperwork to meet demand from migrants who were desperate to get out of overcrowded shelters in a program that didn’t thoroughly vet properties and landlords.

The state would end up paying rent for months for places where people weren’t living. And, even for places migrants did live, it would often be charged $140 or more above market rate for apartments migrants often found uninhabitable in neighborhoods considered among Chicago’s most violent.

At the same time, landlords would say they had little incentive to participate in a program that seemed loaded with risk: The state’s rental assistance was short-term, and the tenants were mostly unemployed.

Over an 18-month span through June, the state would pay more than $50 million to cover the rent of more than 6,000 families and, in the end, ask dozens of landlords to pay back more than $620,000 amid complaints that the properties were unlivable.

Fuentes would get a front-row seat to it all.

Hope

In the earliest months that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began busing migrants to Chicago, the city scrambled to set up temporary shelters while state officials devised a bigger plan.

Flush with federal grant money, in December 2022 the Illinois Department of Human Services teamed up with the Illinois Housing Development Authority for a program that would eventually provide millions of dollars to help resettle migrants from city-run shelters to rental housing.

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s then-deputy chief of staff Cristina Pacione-Zayas told the Tribune that the Asylum Seeker Emergency Rental Assistance Program was the city and state’s ultimate solution to responding to the crisis. At the time, the city’s shelters had already received reports of overcrowding and bad food.

“You can characterize our strategy as ultimately resettlement,” Pacione-Zayas said in June 2023.

Fuentes’ family, who got to Chicago in mid-August, could particularly benefit from being resettled.

Her husband, Johan Pedroza, had already been hospitalized in Chicago for complications from an open-heart surgery several years ago. He couldn’t handle strenuous activity and had to go to weekly physical therapy at the hospital, paid for with state-funded insurance.

Their 15-year-old daughter has lupus and epilepsy, and by the time the family arrived in Chicago, the teen had developed a wound in her spinal cord. She was transferred immediately to the hospital and had two surgeries.

Then, she had a bad seizure. For weeks afterward, she struggled with short-term memory loss.

At the shelter, with her husband’s and daughter’s frail conditions, Fuentes said her family was told by shelter staff it was best to avoid any risk of infection by staying in their room. Shelter workers said they provided food and extra support for the family, but much of the caregiving duties fell on Fuentes’ shoulders since her husband couldn’t help.

She changed her daughter’s linens multiple times a day so the wound wouldn’t get infected. She got up early to work at a flea market so she could afford the higher-calorie food that doctors said the teen needed and wasn’t provided at the shelter. And she had to juggle all of that while taking her husband and daughter to their many health appointments.

At least an apartment could provide more space than a hotel room, she thought. And Fuentes was set to get help landing an apartment.

Under the program, migrants were paired with state-contracted case managers from Catholic Charities and other nonprofits to help them navigate the housing market.

However, unlike traditional public housing, where landlords and units undergo a formal vetting process, because of the sense of urgency and overwhelming demand from migrants, the state fast-tracked the process. Caseworkers performed only more surface inspections of code violations. The state would rely on community organizations to distinguish good landlords from bad.

The program would — an IDHS spokesperson later explained — also give asylum-seekers “coaching” on how to spot landlords acting suspiciously.

Tough market

Migrants would enter a tight market for low-income renters — with one advocacy group estimating that for every 100 extremely low-income households looking to rent this year, just 32 affordable places would be available.

And in those early months of the program, landlords had expressed trepidation to participate. After all, the bare minimum for accepting a tenant, according to landlords, is typically proof of employment — which many migrants don’t have. How could landlords be sure migrants could make rent once the state stopped paying?

One real estate professional willing to help: Lori Wyatt. She owns a property management company, Good Karma Estates, which is basically a go-between for renters and property owners who oversee leases and maintenance.

She told the Tribune that she first got involved in the housing program last summer after she’d volunteered to help dozens of migrants who were camped out at police stations. She saw an opportunity to make money and do good.

In November, Wyatt and her California-based business partner had found themselves with dozens of vacant houses that they meant to flip — or buy and then sell quickly for a profit — but couldn’t because of rising interest rates. So, they began renting them to migrants through the program.

That same month, twin trends had pushed the program into overdrive: Colder temperatures had forced city officials to cram migrants into overflowing, abandoned warehouses and buildings and the state had announced the program would be cutting back rental assistance from six free months to three after Nov. 17.

In the week before the Nov. 17 deadline, there was a mad dash by migrants to secure housing.

“Everybody went crazy. It was like a feeding frenzy,” Wyatt said.

Wyatt and her husband, Derek Light — who helps manage the properties — worked on the interiors of their houses to prepare them for migrants eager to leave crowded shelters.

“(Our properties) were in very bad disrepair,” Wyatt said. “But everyone was desperate to get out of the shelters.”

According to caseworkers who spoke with the Tribune, migrants were in such a hurry to secure the six-month rental assistance before the deadline — and the caseworkers were trying to meet that demand — that they did not have time to take everyone on walk-throughs of potential properties. Migrants signed leases for apartments that hadn’t been properly vetted.

“Our clients didn’t know what they were getting into,” said Maria Campos, one of the state-contracted caseworkers who assisted migrants at the Inn of Chicago.

Fuentes was one of those people.

`Destroyed`

Fuentes signed a lease for one of Wyatt’s apartments on Nov. 17, records show, the last day to lock in the program’s more generous six-month payments.

It was for a nondescript Morgan Park bungalow on 112th Street, in the southern band of a cluster of South and West Side ZIP codes where most migrants were sent by the program.

Recollections vary about just how much Fuentes was able to vet it before signing the lease. Fuentes told the Tribune she never took a tour and only saw pictures. Wyatt and a state spokeswoman said Fuentes did tour the home before signing. But regardless, there was little dispute that the home was not livable when Fuentes prepared to move in.

About a week after signing the lease, Fuentes, her husband, her caseworker and Light walked inside and immediately noticed the floor was wet. Dust particles floated through the air. The ceiling, she said, was falling in.

“We opened the door, and everything was destroyed. Everything. The water pipes had collapsed, the roof was destroyed,” Fuentes said.

Fuentes snapped pictures on her cellphone, which she provided to the Tribune, showing gaping holes in the ceiling and destroyed drywall.

Wyatt said they were just as surprised. She acknowledged the home was in disarray but said it had been “pristine” just a few days before the pipe broke.

“It gets cold here — like that happens,” she said. “It wasn’t like we were trying to do someone dirty by having a pipe break.”

Fuentes said she never moved into the home on 112th Street. But that didn’t stop the state from cutting a check to Wyatt’s firm, records show, for $10,322 — the equivalent of four months’ rent.

When asked why she accepted the money for a property that no one was living in, Wyatt said it was because she was planning to move Fuentes into another one of their properties instead.

“We had to try to find her something,” Wyatt said.

Fuentes said that her caseworker with Catholic Charities told her not to contact the organization or anyone at the shelter about the 112th Street home’s condition — that everything would be resolved between the caseworker and Wyatt.

Catholic Charities did not answer questions about why the state paid for a place a migrant had never moved into. The state didn’t immediately demand the money back. Records do not say why.

“All checks are sent to landlords prior to move in. The property was previously viewed by the tenant who then agreed to move in,” IDHS spokeswoman Daisy Contreras said in a statement.

Fuentes and her family remained at the shelter, which was paid for by city taxpayers, while the state paid for an unused home on 112th Street.

Squatters and crime

After Fuentes found the first property unlivable, she said her caseworker continued trying to help her find an apartment; she shared the texts she and the caseworker sent back and forth with the Tribune.

On Dec. 5, Fuentes was offered a second house in West Pullman, on the 11500 block of South LaSalle Street, also with Good Karma.

A new lease was not submitted for the second property, according to state records. Instead, Wyatt told the Tribune that she used the money from the first property to prepare the second property for Fuentes.

But when Fuentes met Light at the LaSalle property in December, there were other migrants living inside.

That didn’t surprise Wyatt and Light. They said they often allow migrants — even to this day — to stay at their vacant houses on the South Side so the properties won’t get broken into. In this case, they said, these migrants didn’t want to leave. So Light said he paid those migrants $3,000 to move out, a tactic not unheard of by landlords looking to avoid a messy court fight.

A few days later, Fuentes visited the property again on her own. The squatters were gone, but she found it in disrepair, according to emails to the state from her caseworkers. The electricity only worked in the kitchen. The heater was not operating efficiently, and several of the doors were broken.

The broken doors especially scared Fuentes. She was worried about squatters getting back into the apartment.

“Is there any way (Fuentes) can be moved to another apartment as this apartment isn’t safe for her and her family?” wrote Melanie Jaramillo, a caseworker helping Fuentes, in an email to Wyatt dated Jan. 8.

State emails show it took several weeks to repair the inside of the apartment.

And it is unclear if Fuentes moved into the second unit or not; she says she didn’t, but Wyatt said she did, for at least a week anyway.

Regardless, by late February, and still in the shelter, Fuentes told her caseworkers she wouldn’t move into the South LaSalle apartment because she wasn’t comfortable there.

She said it felt dangerous and there wasn’t a school or hospital nearby for her family.

A Tribune analysis found that migrants were more likely to be sent into neighborhoods with higher rates of shootings — perhaps not a surprise in a housing market that struggles to provide safe, affordable apartments across the city.

Of 58 ZIP codes in the city that could be studied, the second apartment — which Fuentes turned down — had the 11th highest rate of shootings, per resident, in 2023, according to the Tribune’s analysis of city data.

Chicago police data show that last year, officers had taken five crime reports on that block — ranging from somebody shooting a gun off in the alley to vandalism, two thefts and an aggravated assault.

Fuentes’ fears were also felt by other migrants who later moved into the home. When a Tribune reporter and photographer visited them in late March, they said they’d been living at the state-funded, $2,185-a-month apartment for about a week, connected by the same Catholic Charities caseworker who’d sent Fuentes there months earlier.

The new tenants said they were scared of the neighborhood and were thinking of moving their family of six somewhere else. In fact, three months later, they did just that when their three months of rental assistance ran out.

But Wyatt had a different take on the migrants’ fears. She told the state that Fuentes had described her feelings about the neighborhood in racist terms.

Fuentes denies those allegations, saying she never said anything racist and that she didn’t accept the house because it was in such bad condition, not because she had any animosity toward her neighbors.

Tension between migrants and the existing communities is not unusual, said Andre Barnes, HBCU engagement director for NumbersUSA, who studies how immigration is affecting Black Americans. He said migrants are being concentrated in neighborhoods without connection or resources, which can lead to discomfort for both newcomers and residents.

“How could (Fuentes) be comfortable? She’s in a different country. She’s not in a neighborhood where there are a lot of people that look like her,” he said.

Anthony Beale, alderman for the 9th Ward where the La Salle property is located, said the state should not be putting migrants with high needs into his ward.

“The African American community is being stepped on by people who are just coming across the border illegally. Our communities need resources as it is,” he said.

One more try

In early April, still living in the same hotel room four months after getting that email welcoming her to the program, Fuentes was offered a third apartment by Good Karma, this time in New City.

The state issued a second check to Wyatt, this time for the third apartment, at a rate of $2,182 a month, for six months of rental assistance. She had now received two separate payments for Fuentes’ housing.

The third apartment was on a block with even more reported crime last year than the second house, in a ZIP code with an even higher rate of shootings than the others.

When Fuentes toured it with her new caseworker, there was no heat or hot water, emails show. A valve in the basement was leaking and the shower faucet wasn’t installed. She had to wait several more weeks in the shelter hotel room.

Wyatt said she offered Fuentes several properties in the south suburbs, but Fuentes declined them because they weren’t close to a hospital. Wyatt had no other open apartments available, she said.

“There is nothing. There are no homes available on the South Side for these people,” said Wyatt.

Fuentes said she didn’t feel safe at the third apartment either, plus she believed the monthly rent was too steep for the home’s size and location. After all, she’d soon need to make rental payments herself.

As the sole breadwinner, she said she earned roughly $200 a week selling handmade crafts and nonperishable food at the Swap-O-Rama flea market in the Back of the Yards neighborhood.

She got her work permit with the help of government officials about two months ago after applying for it in December and has been looking for a better job since.

In the case of the third apartment, a Tribune analysis of Zillow data shows that Fuentes’ monthly rent of $2,182 was set at $623 above the median for that ZIP code, part of a trend in which the state often paid landlords more than average for a place.

That’s not unusual for the program. Of properties in ZIP codes with enough rent data to study, the analysis found the state routinely paid more than the median rent charged in that ZIP code at the time the lease was inked. The state typically paid $147 extra a month.

Under the state program, landlords were allowed to charge only “fair market rent,” but that’s defined by federal rules, and sets maximum prices based on the number of bedrooms. In the ZIP code of the third home, in New City, the federal government allowed a maximum monthly charge of $2,182 for a three-bedroom home, and that’s what Good Karma ended up charging.

However, landlords point out that housing migrants comes with hidden costs and extra risk — as most migrants don’t speak English and often are unemployed. Some landlords said they also took the highest market rates because it was the only way they could make an income with such a high tenant turnover rate.

Landlords involved in the program told the Tribune that, of migrant leases, about half their tenants have already left, far more than other types of renters.

Corey Oliver, CEO of Strength In Management, rented about 50 units to migrants and said he thought the state’s effort would have been more successful if the rental assistance had been longer than six months — enough time for migrants to get stable work and become independent.

“Why would you change a yearlong lease for a six-month lease to go to a migrant?” he asked. “There’s not enough upside for us to deal with the consequences.”

In all, firms tied to Wyatt were paid $560,504 in 59 separate payments under the migrant rental assistance program, according to state data.

Wyatt defended the rent, saying even the maximum amount she could charge wouldn’t be enough money for a population that is so difficult to house. She views high rents as merely “upfront costs” to help cover translation services for migrants and the “arduous” required paperwork.

“We’re clear on the fact that there’s no way these people are going to pay $2,100 a month for a three-bedroom in that area when the program is over,” she said.

In a program that began with high aspirations to address an unprecedented crisis, there have been success stories. Thousands of migrants have moved into homes; some are able to take over the rent. Shelters have gotten emptier; some have even closed.

Norman Shanker, a property manager who rented over 20 units to migrants under the program, said he’s been able to keep about 80% by decreasing rents after the program assistance runs out.

Tension

But migrant advocates argue that the rents were overpriced, driven by landlords gouging the state program, and they fear a wave of evictions of migrants in the late summer and fall.

South Side volunteer Erika Villegas said rental scams were common.

“We do see and hear of instances where tenants are being taken advantage of — where there are units that have mold and no hot water, heat that is kept at 50 degrees (in the winter),” said Villegas, a real estate agent who has helped migrants with their housing needs. “A lot of families are afraid to report a bad housing provider.”

The state did document some problems with landlords. Records show migrants turned apartments down several times because of “unsafe living conditions.” A few caught fire.

One tenant and landlord got into a verbal altercation and then the landlord refused to turn over the keys. Another tenant was shown a second-floor apartment but given keys to the basement and told that the “upstairs unit is for Americans.”

The state eventually demanded dozens of landlords pay back more than $620,000 — about $175,000 of which was repaid as of late June, according to the most recently available state data.

Wyatt and Light stressed that the rental assistance program provided no continuing support for migrants struggling to pay rent. They said they weren’t prepared for the auxiliary costs that came in the form of management and time educating their migrant tenants.

The couple’s experience housing migrants ran the gamut: They said they had dozens of people doubled up in one or two bedrooms; they had one group of tenants destroy their properties; they dealt with loitering complaints from neighbors; they helped people from tropical climates understand what it meant to pay a gas bill in the winter.

Fuentes’ case, they said, was particularly challenging — because of her family’s high needs and her series of back-to-back misfortunes.

It was a challenge that, state notes suggest, the state was slow to understand.

The notes, obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, show a haphazard state effort to keep tabs on Fuentes and Wyatt. Workers phoned and sent emails in January to both Wyatt and Fuentes — who was still in the shelter — looking to finalize the paperwork for the fifth and sixth months of rental payments for the first unit. They got no response.

Records show that by February, the state learned Fuentes never moved into the first apartment in December because of the damage and that, if Fuentes had moved into the second unit offered by Wyatt, it was for only a brief time. Wyatt had told the state she’d used the cash paid for the first unit to fix up the second unit for Fuentes.

By late February, a state worker noted the case was “under escalation.”

In late March, after the state said it repeatedly struggled to reach Fuentes by phone and email, it officially “recertified” her for the program, only to decide in early April to stop any payment on it.

“It appears the tenant is still in the shelter. Even though the tenant was having issues with the landlord originally, the original application … was approved,” according to the April 4 note, ending with the admonition: “DO NOT PROCESS RECERTIFICATION until Okay is provided by Management.”

A week later, Wyatt’s property manager Karyl Reed wrote an email to Fuentes’ caseworkers on April 11: “We have all spent a lot of time on this when there are so many other families that need our help … I am of the opinion that we should all cut our losses and move on.”

The choice

For Fuentes, the heavy optimism she felt around Thanksgiving had given way to despair by April.

“It feels like the walls are closing in on me,” she said at the time. “I don’t know what to do. I haven’t been able to get answers.”

She’d been to three places. None felt safe for her family. They were still in the city-funded shelter, in the small hotel room they’d called home for eight months — four of those at a time the state was also paying for them to live elsewhere.

But she knew she couldn’t stay in the hotel forever.

Feeling pressure to leave, Fuentes on June 7 moved out of the shelter and into the third apartment with her family, after the unit’s hot water was restored and the faucet fixed.

It had taken her three months to get to the United States from South America and nearly 10 months to move out of the Inn of Chicago.

Although her block is quiet, she’s heard of gang violence in the area and fears for her family’s safety. Fuentes said her husband and kids can’t sleep because they’re scared.

“(My 10-year-old) cries at night because he’s so hot,” she said.

In her New City unit, painted screws and patches cover up holes in the wooden floor. On a warm day in June, even open windows and Febreze did little to stifle the overpowering smell of mildew that seeped up from the basement into every room.

Fuentes said she appreciates having a home, and getting extra state help for it, but knows this is not the kind of life she’d hoped to be able to provide for her family in the United States.

She’s not sure what the future holds. Hopefully, she’ll find a new place, one that she can afford on her own.

Or, she fears, come next Thanksgiving, she’ll be back at the shelter.