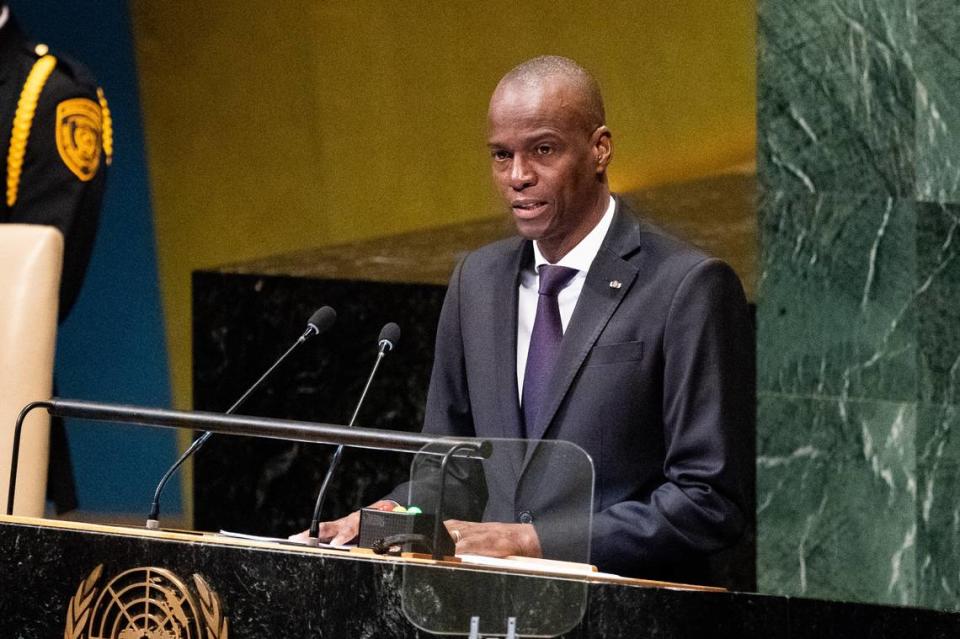

Moïse’s rivals recruited Haiti’s gangs in deadly plot 3 years ago. Did they play a role?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the international plot to kill Haiti’s president, his political rivals enlisted a Miami-area security firm to hire a squad of ex-Colombian soldiers to carry out the assassination and replace him with a hand-picked successor, according to federal authorities.

But in the days leading up to President Jovenel Moïse’s July 7, 2021 assassination, his plotters realized they were missing the support of a critical constituency: Haitian gangs, court records show.

The political rivals met with several gang leaders and asked for their support in the run-up to the assassination of the president at his suburban home in the hills above Port-au-Prince, according to a document filed in an unrelated federal weapons-smuggling case.

One of the rivals suspected of being present was an ex-senator who aspired to be the country’s next prime minister but who would later admit to making contact with gang members as part of his guilty plea in Miami federal court to conspiring to kill Moïse. One of the gang leaders present would later become one of the FBI’s most wanted fugitives with a $2 million award for information leading to his arrest in connection with the kidnapping of 17 missionaries, all but one of them U.S. citizens, court records show.

The records reveal for the first time that Moïse’s political rivals met with a handful of gang leaders to solicit their help in the deadly assault plan on Haiti’s president three years ago. But in the end, the support of key members of Haiti’s ruthless armed gangs didn’t really materialize in the shocking slaying of Haiti’s leader. Moïse’s death did create a power vacuum that allowed hundreds of gangs to terrorize Haitians in one of the nation’s most violent and destabilizing periods.

Three years after the brazen assault, Haitians are no closer to learning the full extent of the complicated web of plots driving the killing of Haiti’s president and all who may have played a role. Two parallel investigations have provided substantial details, but a recent gang raid on Haiti’s National Penitentiary has led to the escape of a number of suspects, including the head of the security unit charged with protecting Moïse’s life.

Still, as U.S. prosecutors prepare to try five of the 11 defendants in U.S. custody who have not been condemned after pleading guilty, additional details have emerged in federal court records. The latest is about the armed criminal gangs, and the efforts to include them in the deadly overthrow.

Gang leaders’ connection to assassination plot

The gang members’ knowledge of the coup plan was mentioned by a confidential witness in a 47-page sentencing memo by prosecutors in the federal weapons-smuggling case against Germine “Yonyon” Joly, the self-described “king” of Haiti’s notorious 400 Mawozo gang.

Prosecutors do not say who the witness was, noting only that he was someone familiar with Joly, 31, and identified him and other gang members as participating in the pre-assassination meeting from photos. Nor do prosecutors identify Moïse’s rivals by name. They also don’t specify the date of the meeting, though it took place close to the assassination.

“The political rivals told the gang members about the planned assassination of President Moïse and asked for their support and silence,” according to the confidential witness, who provided his recollection of the meeting to the FBI. “The gangs were made promises in order to obtain their support. These promises were not kept.”

Joly, according to the memo, was chosen as the gang’s representative at the meeting and participated by phone from a Haitian prison, where he not only controlled the gang’s hostage-taking operations but directed arms purchases and deadly attacks.

Extradited in May 2022 to the United States in connection with the kidnapping of 16 U.S. citizen missionaries on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince, Joly was sentenced last month to 35 years in prison for his role in the purchasing and trafficking of firearms from Florida to Haiti to benefit his gang’s criminal activities. The guns, prosecutors said, were bought using the ransom payments extorted from kidnapped Americans.

READ MORE: Plots, subplots and betrayal engulfed Haiti’s president before his assassination

In seeking life in a U.S. federal prison for Joly, prosecutors sought to show his control of the high-profile gang, 400 Mawozo, since before July 2021. Prosecutors also mentioned the meeting as proof of his control of the gang and its involvement in the abduction of the missionaries as they passed through the gang’s territory after visiting an orphanage. The majority of the hostages, whom Joly also saw as “the ticket for him to be released from jail,” were kept in captivity for two months and freed only after an unspecified ransom was paid.

The FBI’s witness said he heard statements by Joly that he intended to keep the missionaries captive “as a consequence to the politicians not keeping their promise to gang leaders.”

Prosecutors say Joly agreed with Vitel’homme Innocent, another gang leader, to commit kidnappings, including that of the missionaries and split the profits. Innocent is the leader of the powerful Kraze Baryé gang, which is among the armed groups currently plunging Haiti into lawlessness.

According to the FBI’s witness in Joly’s weapons-smuggling case, Innocent attended the pre-assassination meeting with the president’s political rivals. Last year, he was added to the FBI’s most wanted fugitives list.

Three years after killing, Haitians no closer to answers

Three years after Moïse, 53, was shot 12 times and violently beaten in the middle of the middle-of-the night while his wife was injured, questions remain about who may have known about the plot to kill him—and may have been in on it.

The investigation in Miami and the other in Haiti, have so far failed to yield a motive or definitively say who fired the fatal shots.

In Miami, a half-dozen men have pleaded guilty in the assassination case in federal court, which is built upon a violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act and a conspiracy to kill a foreign leader.

Prosecutors say the plot pivoted on planning in South Florida and Haiti, with the initial goal of replacing Moïse with a Haitian physician and South Florida pastor, Christian Emmanuel Sanon, and deploying the former Colombian soldiers to carry out the president’s murder.

READ MORE: Who was involved in killing of Haiti president Jovenel Moise?

Among the six defendants convicted is Joseph Joël John, a former Haitian senator. John admitted in his factual statement as part of his guilty plea that between April 2021 and July 7, 2021, he conspired with nearly a dozen other Haitians, Haitian Americans, Colombians and South Florida business associates “to prepare for and carry out the forcible removal of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse by kidnapping and/or assassination.”

The former lawmaker, who is known in Haiti as John Joël Joseph, admitted that he helped secure rental vehicles and procure weapons for the coup operation. He also admitted providing advice to his fellow plotters, with whom he met with in both Haiti and in South Florida, and making introductions to gang members because he and his co-conspirators wanted their “support.”

An opponent of Moïse, John’s role first emerged in the Haitian police investigation of the killing. Police say he went to rent five vehicles on June 21, 2021 for three days, according to a report first obtained by the Miami Herald. Among the four people who had accompanied him was Innocent, the gang leader and ally of Jolly’s who would later rise to prominence and power in his absence.

Wanted by Haitian authorities for his alleged role in the plot, Innocent has never presented himself for questioning. In a May 2022 interview with journalists, he spoke of having ties with several political rivals, some of whom were part of the new government put in place after Moïse’s death. Without offering details, Innocent spoke of having taken “certain engagements” with the president’s rivals, some of whom would later sign a political agreement to consolidate the power of Ariel Henry, a neurologist who was chosen by Moïse to run the government but would later face a power struggle after the president died before he could be sworn-in.

“I speak to several political parties, several political leaders. But that doesn’t mean I have a link or a relationship with John Joël Joseph and what he was doing,” Innocent said in the interview published online. He admitted to having a relationship with John but went on to say that he can have a relationship with someone without knowing what’s going on outside of their relationship, and the same goes for the political parties.

The remaining defendants in the U.S. case who have admitted to involvement in Moise’s assassination, which began as a coup to remove the president, are: Joseph Vincent, a Haitian American who worked as an informant for the Drug Enforcement Administration; Germán Alejandro Rivera Garcia, aka “Colonel Mike,” a former Colombian military officer who ran the commando squad; and Mario Antonio Palacios Palacios, a former Colombian soldier recruited by Rivera. Along with John, they were sentenced to life in prison, but they are cooperating with federal prosecutors and the FBI in the hope of receiving lesser time.

In May, a sixth defendant, Frederick Bergmann, was sentenced to nine years in prison for breaking federal laws meant to keep the U.S. out of overseas conflicts. A resident of Tampa, he was sentenced to a year less than the maximum for shipping ballistic vests to Haiti that were used by the Colombian commandos who carried out the deadly attack on the president.

READ MORE: How a Miami plot to oust a president led to a murder in Haiti

Bergmann had no idea the vests were going to be used in the conspiracy to kill Haiti’s president, according to federal prosecutors and his defense attorney. That’s why he wasn’t charged with the conspiracy targeting Moïse .

The remaining five defendants who will stand trial, including Sanon, are charged with conspiring in South Florida to kill Haiti’s leader. The conspiracy charge carries up to life in prison.

The defendants facing trial are: Antonio “Tony” Intriago, the head of a Miami-area security firm, Counter Terrorist Unit Security or CTU; Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, who was a former FBI informant when he joined Intriago at CTU; Walter Veintemilla, a Broward County financier; James Solages, a Haitian American; and Sanon, who was initially seen by the group as a successor to Moïse as Haiti’s president.

Dozens indicted in Haiti inquiry

In Haiti, dozens of people including the president’s widow, Martine Moïse, former Prime Minister Claude Joseph and ex-Haiti National Police Chief, Léon Charles, have been indicted by an investigative judge, Walther Wesser Voltaire. All have denied the charges while Joseph, defending himself and Martine, accused Henry of weaponizing the Haitian justice system. Henry, who had come under scrutiny due to a phone call he had received from one of the indicted suspects, Joseph Félix Badio, after the killing, was cleared of any wrongdoing in the 122-page indictment report. Badio had claimed to be a plant, sent by those close to Moïse to gather intel on those seeking to rid the country of him.

A source familiar with the investigation said the issue of gangs came up during Voltaire’s inquiry. The conclusion reached by the limited inquiry was that Haiti’s gangs, despite the outreach by Moïse’s rivals, were divided over what his fate should be.

“Some were for assassination and others were for arrest,” the source said.

During his inquiry, Voltaire also tried to explore the accusations made by Innocent and his possible ties to those in power during Henry’s unpopular tenure as prime minister. He resigned in April as gang violence threw the country into chaos.

Asked about claims Badio and Innocent somehow had a hand in his accession to power and he had not honored commitments to them, Henry, according to a brief transcript the judge providing in his ruling, replied: “Anyone can spread any information, true or false, virally and anonymously.”

“I had a hard time imagining that the President, in proposing me to be his prime minister, made his decision on the advice of a wanted criminal and a person suspected of having plotted at the same time to assassinate him,” Henry said. “These are nonsense and fabrications.”

Henry, who had denied any involvement in the plot, was cleared by Voltaire’s inquiry.

At the time of the planning, Moïse was growing in unpopularity and questions about when his presidential term ended dominated the political landscape. While most Haitian constitutional experts said the president’s term ended on Feb. 7, 2021, due to when his predecessor Michel Martelly had left power, the United States and others said he still had a year, citing his delay in taking office due to fraud allegations that led to the race’s rerun.

The disagreement, along Moïse’s one-man rule following his dismissal of parliament the year prior, would fuel the growing opposition and street protests against him.

In seeking Moïse’s overthrow, the plotters sought several avenues. They ranged from encouraging protests as a pretext, to grabbing him and putting him on a plane after he returned from an overseas visit to Turkey in June to utilizing the gangs, who weren’t as powerful as they were today but nevertheless menacing.

In the end, the group settled for having the Colombian commandos storm the president’s compound accompanied by Haitian police and two Haitian Americans pretending to be carrying out a raid by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The fallout of that act continues until today.

Haiti’s crisis of lawlessness continues

Innocent and other gang bosses control more than 80% of the capital and have spread their tyranny to the rice-growing Artibonite Valley. Their violence, which has included armed attacks in the well-to-do suburbs of Port-au-Prince and massacres in working class neighborhoods, led to the State Department ordering the departure of non-emergency U.S. embassy staff and U.S. citizens, and a suspension in its visa operations.

Presently, nearly 5 million Haitians are going hungry due to the violence and nearly 580,000 are homeless after being forced out of their home. The latest upsurge in violence, which began on Feb. 29, helped fueled the forced resignation of Henry and the installation of a new political transition in Haiti where the power is now being shared by one-time supporters of Moïse and those who opposed his rule.

Last month, the first contingent of an armed international force, led by Kenya, arrived in the country after the new transitional presidential council selected a former United Nations civil servant, Garry Conille, to replace Henry and form a new cabinet. During a visit to Washington last week, Conille was asked by the Biden administration to prioritize the staging of elections so that a new president and parliament can take office by February 2026.

Fate of Haiti’s Investigation remains murky

The fate of Haiti’s investigation remains murky. Several of those charged have vowed to fight and are appealing the charges, leaving no room for further investigation. Law enforcement sources who were involved in the investigation said they cannot shed light on the role gangs may or may not have played in the run-up-to the killing because U.S. officials have not given them to either John or two other suspects, Palacios and Jaar, who like John were brought to the U.S. after being picked up in Jamaica and the Dominican Republic, respectively.

Earlier this month, the government prosecutor Edler Guillaume who had overseen the investigation and recommended that Voltaire indict 70 people including Innocent, was removed from his role. Meanwhile, dozens of suspects are among the thousands of prisoners who escaped from Haitian prisons during the gang raid.

With the exception of 17 currently jailed Colombians, who have insisted on their innocence, and Badio, most of the high-profile suspects jailed in the killing in Haiti escaped in the March 2 and 3 raid on Haiti’s two largest prisons. Among those whose whereabouts remain unknown: Dimitri Hérard, the head of Moïse’s presidential security, who is also under investigation in a separate U.S. arms trafficking case.

Pierre Esperance, a human rights defender who has closely followed the Haiti case, says he doubts Haitians will ever get the answers they seek, including who among them today is walking freely and had some hand in the president’s killing.

The reasons, he said, isn’t just due to the lack of access to suspects by U.S. authorities but because of Haiti itself.

“The investigation on the assassination both by [the judicial police] and the investigative judge doesn’t permit for us to know the motive or the intellectual authors of the crime,” Esperance said. “They never identified the person who paid for the assassination of Jovenel Moïse.”

Esperance said if the investigation had identified where the money came from, “it would help to know the motive behind the crime and the intellectual author of the crime.”

In order to achieve this, Esperance said, one would need to know who paid for the assassination. None of the investigative reports by the judicial police and provided to the Haitian judge offer up this information. When the police went in search of it, on the judge’s order, Esperance said “the Haitian banks never collaborated and the Haitian government did not force them to collaborate.”

FBI agents in the U.S. investigation have scoured the banking transactions and wire transfers of the 11 suspects in custody in U.S. prisons. But while the transactions show payments to some of the ex-Colombian soldiers in custody and the purchase of certain gear the Miami security firm used in order to try and make the attack look like an U.S. government raid on Moïse, they do not show large payments suggesting an individual or individuals in Haiti financed the murder.