National Parks Service approves Maryland Rosenwald school as 'candidate' for historic site

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

And then there was one. Around 5,000 schools financially backed by one man and built across the Southern United States over two decades during the early 20th century received increased attention from some members of the U.S. Congress in recent years.

The late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., an alumnus of one of the schools, co-sponsored legislation to potentially preserve some of the sites as part of the National Parks Service.

Months after Lewis’ death and one week after the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, former President Donald Trump signed into law the bipartisan bill, which required a study of over a dozen related sites across the country to see if they’d be fit to become a part of the National Parks Service.

Law required the sites to meet four criteria to be recommended as a National Parks Service unit. A site must have: 1) national significance, 2) suitability, 3) feasibility and 4) need for NPS management. And last month, more than three years after the law was signed, the results of the National Parks Service study came back about the schools built for Black children around a century ago through the philanthropy of Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Only one of the 16 sites was found as a “candidate” to be a national historic site.

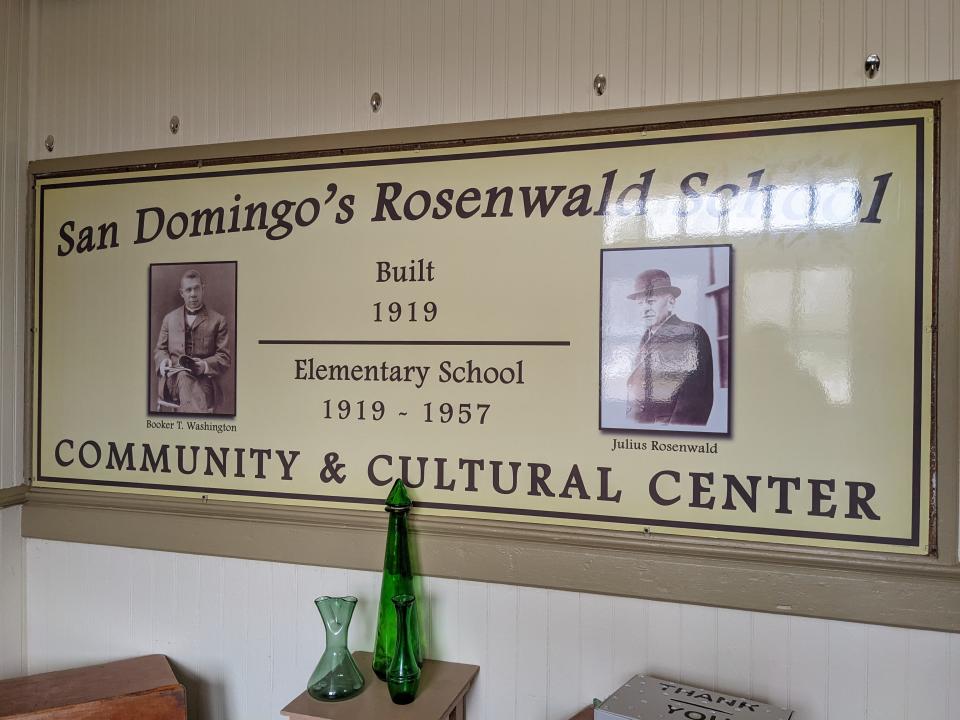

And that one — the San Domingo School — happens to be in Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, specifically in Sharptown in Wicomico County.

More: Maryland Superintendent of Schools embraces 'once-in-a-generation' opportunity

‘This is where we got our educational foundation,’ Rosenwald alumna says.

Barbara Purnell does not have to talk about the impact the Rosenwald schools had on the nation. She can talk about the impact one of the schools built on Maryland’s Eastern Shore had on her.

“This is where we got our educational foundation,” said Purnell, an alumna of the Germantown School, a Rosenwald school in adjacent Worcester County, during a June 27 phone interview.

Speaking from the school site in Berlin, restored as the Germantown School Community Heritage Center in 2013, Purnell laid out the contours of her life’s path after attending the Rosenwald school prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that ruled “separate, but equal” schools for Black and white students unconstitutional.

She is now the president of the Germantown School Community Heritage Center. She taught at Head Start, the early childhood education program. And she worked for nearly 30 years at the Assateague Island National Seashore before retiring in 2006 from the National Parks Service.

Purnell’s former employer, the National Parks Service, sent the study and San Domingo recommendation to Congress on June 13, 2024, for the federal legislators' consideration. As the National Parks Service news release from that same day indicates: “Additions to the National Park System are designated by acts of Congress or through presidential proclamation.”

With congressional action pending, a Daily Times reporter asked the Rosenwald school alumna Purnell: “Why it is important for the National Parks Service to tell the story of the Rosenwald schools?”

“Because everyone is not acquainted with it,” she said, “and it’s good for people to know.”

More: Find out where Maryland ranks in national report with four key education areas

The origin story of the Rosenwald schools

The story of the Rosenwald schools starts with two men whose lives started in different places, but whose paths crossed as they worked to build a better and more just United States of America.

Booker T. Washington’s story started on a Virginia plantation nine years before the end of the Civil War. His 1901 autobiography “Up From Slavery” documents his rise from the plantation to the coal mine to working for an education in Hampton, Va., before becoming the founding principal and first president of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, and a national figure.

Julius Rosenwald’s story started during the Civil War in Springfield, Illinois, one block from the family home of Abraham Lincoln, then directing the war effort for the United States as president.

In 1895, as an adult, Rosenwald got involved with Sears, Roebuck and Company, which sold products across the nation, ranging from furniture to farm equipment, while pioneering catalog marketing. By 1907, one year before Rosenwald (then a company vice-president) would become the company’s president, the annual revenue of Sears was $5 million, according to the National Parks Service website.

Rosenwald, whose parents were German immigrants who met in Baltimore, learned of the situation of Black Americans by reading Washington’s autobiography “Up From Slavery,” according to a document on the Maryland Historical Trust website. The two men met when Washington visited Chicago in May of 1911. Rosenwald then visited Tuskegee, Alabama, soon after, eventually agreeing to become a member of Tuskegee’s Board of Trustees.

In 1912, Rosenwald donated $25,000 to the Tuskegee Institute, and Washington convinced him to use a portion of that amount ($2,800) to build six small rural schools in Alabama, with half of the money for each school coming from the Rosenwald money, the document said. Those schools would be the start of hundreds, then thousands, of rural schools designed by a Tuskegee architect and built through the South through the Rosenwald partnership.

More: Edmunds: Lessons from Booker T. Washington

Rosenwald schools in Maryland

“In the state of Maryland, between 1918 and 1932, 156 schoolhouses were constructed in 20 counties,” according to a document about the schools on the Maryland Historical Trust website.

The document includes information from a 1919 Annual Report of the Maryland Board of Education, which shows the state of Black schools during that period of legal segregation.

“The need for better buildings is really pressing,” reported Maryland State Agent for Negro Schools J. Walter Buffington, in the annual report for the year ending July 31, 1919, “The present condition is a result of a partial failure for many years to construct suitable schoolrooms for the colored people. From a survey made of the State, I find that 27 schools are being conducted in churches; 54 in lodge halls; 79 in so-called schoolhouses which are totally unfit for school purposes.”

Purnell’s Germantown School became a reality for $3,200 just a few years later after that report, in 1922-1923, with $700 coming from Rosenwald. It was one of about 50 surviving Rosenwald school buildings in Maryland, documented in 2014 correspondence between a Prince George's County historian and the National Parks Service.

A Washington Post article from that year, 2014, about the San Domingo School on Maryland’s Eastern Shore (citing a currently closed archival database at Fisk University) said the original school received $500 from Rosenwald, $800 from the community and $5,000 from the government. The document on the Maryland Historical Trust website confirms the total cost of $6,300 for the three-teacher school originally built in 1918-1919 with $500 from Rosenwald.

Maryland’s first Black governor, Wes Moore, inaugurated over 100 years after the San Domingo School was built, thanked the National Parks Service for their “recommendation” of the site in a June 25, 2024, social media post.

“Rosenwald Schools like the San Domingo School played a critical role for African Americans during the Jim Crow era, and it’s important that this history is preserved for future generations,” he said. For that to happen via the National Parks Service, Congress and/or the president must act.

The Rosenwald school alumna and National Parks Service retiree Purnell said such a designation would be a “great honor.”

“It would be a great experience for people to learn,” she said, “and (with) the National Parks Service, (there) would be no better place to learn it.”

More: Maryland Conservation Corps paves the way on state park trails and way more

Dwight A. Weingarten is an investigative reporter, covering the Maryland State House and state issues. He can be reached at dweingarten@gannett.com or on Twitter at @DwightWeingart2.

This article originally appeared on Salisbury Daily Times: Maryland Rosenwald school could be future National Parks Service site