Navy To Explore Arming Other Ships With Missiles Amid Constellation Frigate Woes

Congress has demanded the U.S. Navy look into buying a new class of small warships loaded with missiles or adding bolt-on launchers to existing vessels, including amphibious warfare and auxiliary support types, to help increase its combat capacity. Lawmakers ordered the study in response to major delays in work on the Navy’s future Constellation class frigates in large part due to extensive changes in the core design. There is already a long-standing debate about whether the 32 vertical launch system (VLS) cells on those ships are adequate to support their expected mission sets, something The War Zone has previously explored in detail.

The Senate Armed Services Committee included a call for what it termed a “highly producible small surface combatant study” in a report accompanying a new draft of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDDA), for the 2025 Fiscal Year, which was published earlier this week. This follows a series of damning reports on the status of the Navy’s Constellation class frigate program. The future USS Constellation is currently under construction and is set to be delivered in 2029, three years behind schedule. The second ship in the class, which will be dubbed USS Congress, is also facing years-long delays. The Navy has four more of the frigates on order.

“The committee is concerned with the projected decline in the number of Navy battle force ships and fleet-wide vertical launch system (VLS) capacity between now and 2027,” the section of the report on the small surface combatant study says by way of introduction. “The President’s budget request for fiscal year 2025 would procure 6 battle force ships while retiring 19, contributing to these projected near-term declines. Given the ongoing naval buildup by the People’s Republic of China, the committee believes these projected declines increase risk to U.S. forces in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command area of responsibility.”

A key factor in this is the ongoing retirement of all of its remaining Ticonderoga class cruisers, each of which has 122 VLS cells. The service just held a decommissioning ceremony for one of these ships, the USS Vicksburg, on June 28. The Navy is also looking to decommission its four Ohio class guided missile submarines, each of which can carry up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles, by the end of the decade.

When it comes to the Navy’s surface fleets, the stated plan is for Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyers, which have 96 VLS cells, and a new future destroyer design, currently referred to as DDG(X), to steadily fill the resulting gap. The Constellation class frigates, as well as future uncrewed surface vessels, will also help bolster the Navy’s overall VLS capacity.

However, “the committee does not believe the Department of the Navy is adequately emphasizing near- and medium-term capacity requirements,” the recently released Senate Armed Services Committee report continues. “With the delivery of the first Constellation class frigate delayed 3 years and procurement of the large, unmanned surface vessel (LUSV) not scheduled to begin until fiscal year 2027, the committee believes the U.S. Navy needs to focus more on supplementary options for increasing ship numbers and missile-launching capacity in the nearer term.”

The Secretary of the Navy now has until April 1, 2025, to produce a study that addresses the following five points:

“Examine a crewed variant of the LUSV that can serve as a pathfinder for the unmanned version while adding near-term missile-launching capacity, including a discussion of any need for waivers of survivability or other requirements, given the non-crewed original design of the LUSV.”

“Examine other foreign, commercial, or U.S. Government ship designs that are mature and could be adapted with minimal modifications to produce a crewed small surface combatant.”

“Examine existing Navy ships (including amphibious and support ships) or commercial-type hulls that could be quickly modified into missile-firing ships through the addition of VLS, bolt-on, or containerized missile launchers.”

“Evaluate the time to field each platform, as well as the platform’s producibility within current supply chain and industrial base constraints.”

“Provide cost estimates and manpower impacts for each platform.”

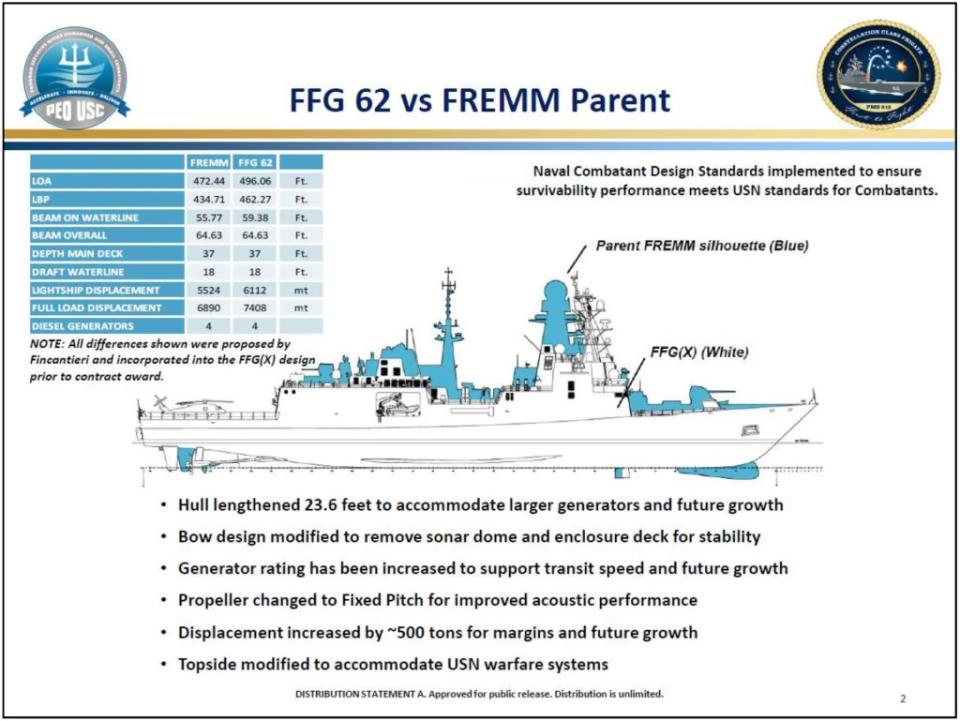

The second stipulation here is immediately notable given that this was the exact plan for the Constellation class, a design ostensibly based on that of the Franco-Italian Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM), or European Multi-Mission Frigate. As it stands now, the Constellations will have around 15 percent commonality with their parent design and the changes could negatively impact the top speed and other operational capabilities of the ships, as well as schedule and cost, as you can read more about here. The Senate Armed Services Committee criticized the management of the Navy’s new frigate program elsewhere in its recent report, which also recommended blocking funding for the ships until the service can provide more assurances that the design is stable.

“The scale and scope of these changes [to the Constellation class design] call into question the basis of the U.S. Navy’s original program justification to Congress and the fixed price contract awarded to the shipbuilder,” the Senate report notes. “If the proposed design was insufficient to meet U.S. Navy standards to the degree suggested by the reported 15 percent commonality figure, then the contract award suggests that there was a severe breakdown between the assumptions of the source selection evaluation board and the senior technical authority.”

Furthermore, “the Secretary of the Navy certified to Congress that basic and functional design were complete prior to the start of construction in August 2022, but U.S. Navy officials now estimate that such maturity will not be reached until more than 2 years later. The committee believes this constitutes a misrepresentation of the facts certified by the Secretary of the Navy.”

The report also stressed that the members of the Senate Armed Services Committee remain supportive, in broad strokes, of the Constellation class frigate effort as an important future addition to the Navy’s fleets.

When it comes to the Navy’s LUSV program plans, the current focus is on acquiring a fleet of uncrewed vessels with displacements between 1,000 and 2,000 tons and between 16 and 32 VLS cells. The service had previously hoped to begin fielding the first of these drone ships in the 2025 Fiscal Year.

The Navy has already been experimenting with various tiers of USVs for use in number of roles, which has included live-fire missile launches, for years now. Many of these existing USV designs are really crew-optional. The expectation has been that any operational LUSVs are likely to have baseline uncrewed capabilities that will be incrementally expanded upon, as well.

See the game-changing, cross-domain, cross-service concepts the Strategic Capabilities Office and @USNavy are rapidly developing: an SM-6 launched from a modular launcher off of USV Ranger. Such innovation drives the future of joint capabilities. #DoDInnovates pic.twitter.com/yCG57lFcNW

— Department of Defense

(@DeptofDefense) September 3, 2021

The idea of expanding Navy missile launch capacity by adding bolt-on systems to other existing ships in its inventory, especially cargo vessels and other auxiliary types, including commercial-owned ones, is also not new. In fact, Congress demanded a previous study into doing just this back in 2021 before it would approve any funding for the LUSV program.

The San Antonio class amphibious warships the Navy has now were also originally supposed to have two Mk 41 VLS arrays, though these were not installed in the end. There have long been discussions about refitting those vessels to finally give them this capability.

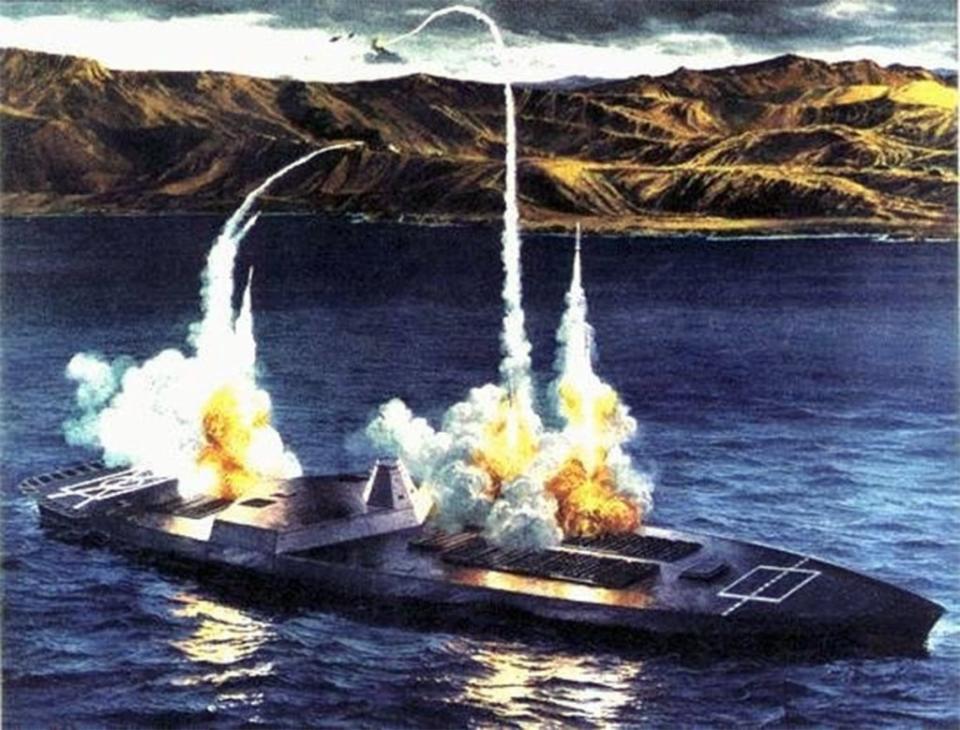

The Navy has been eying many of these options for years as part of broader distributed concepts of operations involving ships loaded with missiles, including dedicated arsenal ships, networked together. Those vessels would not necessarily need to have the same diversity of capabilities as a general-purpose warship, especially when it comes to sensors, and would be able to feed in targeting data from other sources. This, in turn, would allow those platforms to be deployed across a relatively broad area, creating both new tactical opportunities and targeting challenges for opponents. This all fits in with evolving ‘kill web’ concepts the entire U.S. military is increasingly exploring that are ever more important in the face of similarly expanding threat capabilities, especially among near-peer competitors like China.

Arming auxiliaries or commercially sourced vessels does have its drawbacks. In particular, these designs are not designed to the same survivability requirements as true warships.

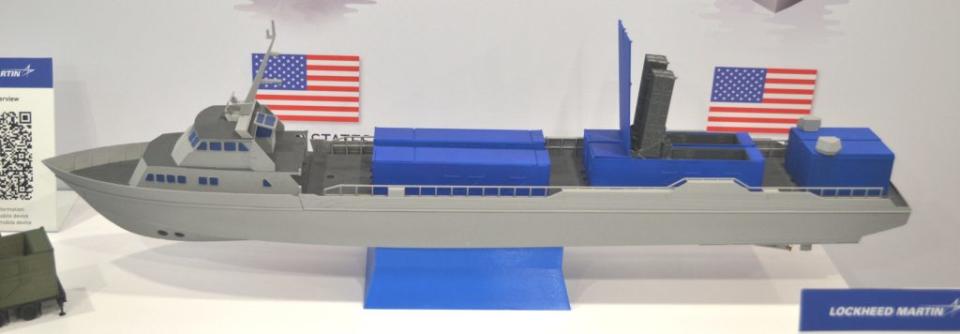

There are a number of add-on and containerized missile launch systems on the market now that could meet this need. The Navy has already been testing a containerized launcher called the Mk 70, which is derived from the Mk 41 Vertical Launch System found on various U.S. and foreign warships, on crewed and uncrewed vessels, as well as in a ground-based configuration.

BAE Systems is also on contract with the U.S. Navy to develop the Next Generation Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile Launch System (NGELS). NGLES will primarily serve as a replacement for existing launchers used to fire RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) on Navy ships and those of America’s NATO allies. NGELS is based on BAE’s Adaptive Deck Launcher (ADL), an angled deck-mounted launch system designed to fire various missiles from the same canisters used with the Mk 41 found on various U.S. and foreign warships. ADL has a modular and scalable design intended to make it relatively easy to integrate on a wide variety of ships, crewed and uncrewed.

Adaptable. Customizable. Lethal.

Meet the Adaptable Deck Launching System. A low elevation, deck mounted launching system that can be configured to any platform, providing critical air defense capability to defeat missile threats.

Visit us at #SNA2024 to learn more. pic.twitter.com/f6ujPnfaoU— BAE Systems, Inc. (@BAESystemsInc) January 9, 2024

Systems like the Mk 70 or the ADL, though flexible in how they can be integrated, does have significantly less capacity than a typical built-in VLS array.

It is worth noting here that the Navy has downplayed using total VLS cells across its fleets as a metric of its combat capacity in the past. The service has pointed to having increasingly more advanced weapons to put in those launchers and other new capabilities as helping to offset losses in overall VLS capacity.

At the same time, the crisis in and around the Red Sea since October of last year and the U.S. response to Iranian retaliatory missile and drone attacks on Israel in April have reignited concerns about the Navy’s fleet-wide missile capacity. Serious questions have also emerged about the service’s ability to replenish its missile stocks and actually get those weapons to ships that need them. Devising ways for Navy ships to re-arm at sea has become a particularly high priority. All of these demands would only be greater in the context of any potential high-end conflict, such as one in the Pacific against China.

There is also the matter of China’s massive advantage in total shipyard capacity compared to that of the United States. This presents its own concerns in the context of the delays with the Constellation class and other Navy shipbuilding programs, and could present limitations for the service when it comes to exploring alternatives in the near term.

What other missile-toting ship options the Navy brings back to Congress next year remains to be seen as it continues to struggle ahead with the Constellation class frigates.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com