‘They never left me alone.’ Fort Worth ministry has helped crime victims for decades

The first few years of their relationship were good. Then María Maldonado started finding needles and little bags of white powder around the house.

“I began to get scared,” she said in Spanish during a recent interview in her cozy, three-bedroom home in Burleson. “I didn’t know anything about these kinds of drugs. I’d heard about them, but I’d never seen them before.”

Maldonado, 40, immigrated to Texas from Mexico when she was 18. She met him at a wood supply company where she had worked for 13 years.

Their relationship soured as her husband’s heroin addiction intensified. They started sleeping in separate bedrooms. He grew more irritable and would sometimes shut himself up in his room with their toddler. She continued to find paraphernalia around the house, but he maintained that he was not using drugs.

At one point, she found him shooting up while their 4-year-old sat next to him watching television.

“I was terrified that he was going to prick or inject my son with it or — I don’t know — all kinds of things were running through my head,” she said.

In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic began to dominate headlines, Maldonado received a shock when she went to pick their son up from school. Her husband and his mother had come with a restraining order against her. The school would not let her take him.

“They didn’t give him to me,” she said, breaking into tears as the memory came rushing back to the present. “They said he had papers from the court and that they weren’t going to give me my child.”

Two weeks later, the pandemic brought life to a grinding halt, and with it her efforts to get Aiden back. The courts closed, her hearings were put on pause. She didn’t know when she would see her son again.

Luckily for her, the lawyers at Fort Worth’s Methodist Justice Ministry were there to help her navigate her way out of what seemed like a hopeless situation.

‘I will stay with you through this night’

On an otherwise empty wall in a downtown Fort Worth office hang three maritime signal flags.

To Brooks Harrington and the team — or “family” as he calls it — at Methodist Justice Ministry, a pro bono law firm for poverty-stricken victims of domestic violence, the flags represent the organization’s core mission.

“Back before ships had radios, they communicated with one another by the pennants,” the 76-year-old Marine veteran said in a recent interview at his office. “If a ship was floundering, for some reason, its mast had come down, or the engine had broken or whatever, and they were in deep trouble, they would put up a set of pennants to signal to other ships.”

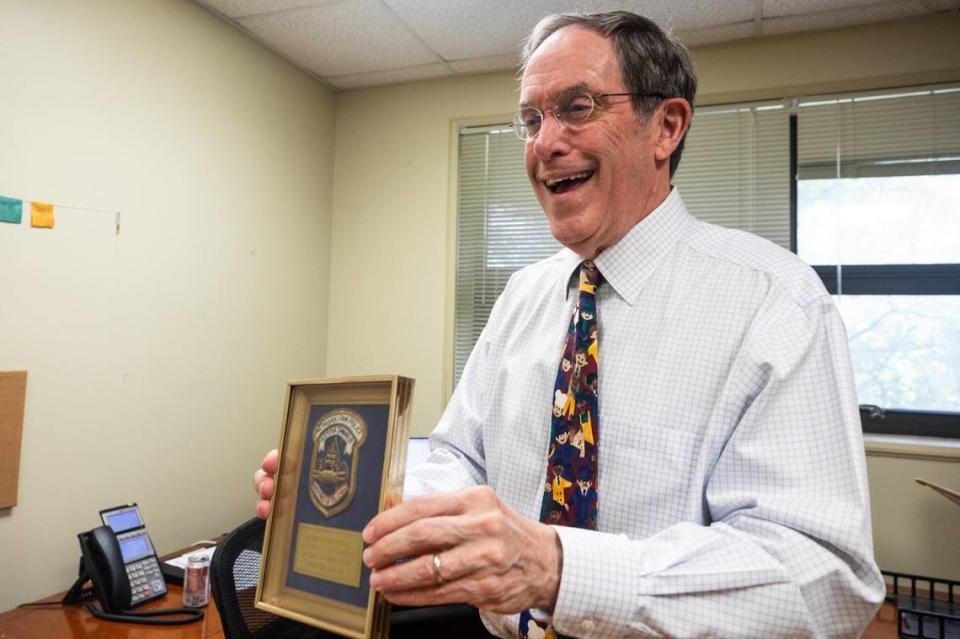

The pennants hung in an administrative office downstairs. In his own office upstairs, nails and hooks studded the walls behind him — a palimpsest of the photos, certificates and honorary police badges displayed there until very recently.

“And hopefully, a ship would come alongside and would run up that combination of pennants,” he continued. “And it would mean, ‘I will stay with you through the night.’ That’s kind of what we’ve done here for the last 18 years.”

Harrington was preparing for his final days at Methodist Justice Ministry, the firm he founded in 2006, and which will be recognized Thursday by the State Bar of Texas’ Legal Services to the Poor Committee.

The Methodist Justice Ministry “not only helps clients with immediate legal needs but also continues to support its clients as they learn to live a life free from violence and move toward independence,” said committee chair Shelby Jean in an email.

The award will be given at the annual meeting of the State Bar of Texas in Dallas.

In 1981, Harrington was working in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Washington, where he shadowed homicide detectives in the nation’s capital. One particular call still haunts him.

“We dived into this brownstone which a slumlord had divided into family units and all the different bedrooms, children were wailing and crying,” he said. “A boyfriend had lost control, gotten angry, too much drugs, had shot his girlfriend and put the muzzle of a shotgun in his mouth and blew the top of his head off.”

They found two young children traumatized in the apartment. Blood had seeped into the room below, where they found two toddlers asleep on a mattress next to a pool of it on the floor.

Harrington later moved back to Fort Worth and made a fortune practicing law — “to the point that I didn’t really need to make money anymore.”

Then he began seeing those children in his dreams.

“In some of the dreams, the 4-year-old would take me by the hand, take me downstairs and show me the kids on the mattress,” he said.

Those dreams led him to leave his successful practice, become an ordained minister and ultimately go on to found the Methodist Justice Ministry.

‘No, mommy, I’m not OK. I’m just a kid.’

Gaby Cena had a child with her high school sweetheart. However, like Maldonado, she unfortunately saw her partner spiral into drug addiction not long after their son was born.

“I endured all the abuse — physical, emotional, verbal — because I was scared of being a single mother,” she said.

The fear of raising a newborn alone compounded her already precarious situation. Born in Guanajuato, one of the most violent states in Mexico, her parents brought her to the United States when she was just 4 years old.

Cena was and still is a recipient of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, the Obama-era policy that gives undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children temporary relief from deportation and work authorization.

She was working at the time, but she couldn’t depend on DACA as a permanent solution to her economic necessities.

“What happens if that ever goes away? Like, what am I going to do?” she said.

Feeling that she needed her partner’s income to support her child, she stayed in the relationship. She stayed until her son saw his father physically abuse her again. She ran to him and asked him if he was OK.

“No, mommy, I’m not OK. I’m just a kid,” he told her.

“That’s really what made me say, ‘No, I gotta go,’” she said.

She sought help, and a former employer referred her to the Methodist Justice Ministry. Harrington represented her, getting a court order to protect her son and later a job as an intake specialist with the organization.

Harrington and the organization have stayed with her through the long and ongoing night of her DACA tribulations. When a delay last year led to a temporary suspension of her work authorization, Harrington kept her afloat financially until she was legally able to come back to work.

“If it wasn’t for Brooks, I don’t know what I would have done,” she said.

Getting the structure in place to survive the founder’s farewell

“That’s Brooks, that’s his DNA,” said Mike Moncrief, former mayor of Fort Worth and board member at the Methodist Justice Ministry. “That’s the Marine in him. That’s the federal prosecutor in him. That’s the faith that he shares and that guides his life in everything he does.”

Moncrief joined the board in 2013 and has watched and helped the organization grow to where it now takes in up to 30 cases a week.

Cena is just one of several employees who started out as clients. The organization helped Norma Serrano Castilla, who was also brought to the United States at a young age, get residency after years of her mother getting scammed by unscrupulous notaries acting as immigration attorneys. She now works as a legal assistant and office manager.

Development Director Yajaera Vázquez Chatterson first came to the Methodist Justice Ministry for legal aid to navigate the process of obtaining guardianship for a nephew.

Hiring people who have been through similar situations as newcomers seeking help has played an important role in achieving the organization’s mission, Moncrief said.

“That’s experience — good or bad — that they can share with our victims, and the victims themselves will know that that lawyer that’s representing them has been there, done that, got the battle scars and survived,” he said, adding that the state bar’s recognition shows that it believes in that mission as well.

Harrington received the bar’s individual award for pro bono work in 2022, but the upcoming recognition is far and away more rewarding.

“This one feels 100 times better, because this is the team,” Harrington said. “Let me correct that: This is the family.”

Incoming Executive Director Erin Landers Lamb finds herself at the helm of this crew that is ready to continue Harrington’s legacy after he leaves.

“They’re a very collaborative group, and they move toward the goal as one force,” she said in a recent interview in her new office. “And the goal is protecting children and survivors of domestic violence.”

While the state bar’s award is a welcome recognition of the work they do, the Methodist Justice Ministry team sees its real value in what it can do to help them further that goal of protecting and supporting people like María Maldonado and now 9-year-old Aiden.

She didn’t see Aiden for over two months, but the organization ultimately helped her win custody, divorce his father and get ongoing protection from his drug use. His visitation rights are conditional: court documents show that he will lose them if he ever fails a drug test.

“They provided me lots of support,” Maldonado said as Aiden played video games next to her on the couch. “They never left me alone.”