'We are not leaving people behind.' Louisville's groundbreaking Fairness Ordinance turns 25

Addressing elected leaders in public was never something Diane Moten thought she would do.

The Louisville native also never thought she'd be out of a job for being herself.

Her own experience with workplace discrimination in the mid-1990s led her to volunteer with the Fairness Campaign, the statewide advocacy organization dedicated to advancing civil rights protections for the LGBTQ+ community in Kentucky.

With some encouragement, Moten started sharing her story as Louisville city government considered adding lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people to its anti-discrimination laws.

She testified about her shock and disbelief when she was fired from her daycare job in Louisville days after telling a colleague she was a lesbian.

“I remember the opposition, these folks coming and talking and thinking, ‘This is so hateful, these words that they're using,'” she said. “If these folks knew me, really knew me, they wouldn't feel this way because I'm not a bad person.”

Moten was among the hundreds gathered in and around city hall downtown on the January evening in 1999 when the Board of Aldermen voted 7-5 to pass the Fairness Ordinance.

As it still does today, it banned LGBTQ+ discrimination in employment, making Louisville one of the first cities to adopt protections for both gender identity and sexual orientation, joining Minneapolis, Los Angeles and Seattle, among others.

Building on its win with city government, supporters lobbied the Jefferson County Fiscal Court in October 1999 to pass a broader ordinance that also covered housing and public accommodations (public and privately owned providers of goods and services). Two years later, city government followed suit.

It took four votes spanning nine years to pass the city ordinance, underpinned by more than a decade of community organizing to build enough public support and political will at a time when no such protections existed in Kentucky.

The timeline of the fight for queer rights in Kentucky doesn’t start or end with Louisville’s Fairness Ordinance. And while the milestone still stands today as a testament to the power of sustained effort and coalition building, the quarter-century anniversary comes as activists are concerned about recent legislative activity in the Kentucky statehouse, including a law limited gender-affirming care and bills that would have restricted drag performances and, they say, weakened local fairness ordinances.

“We're in an atmosphere right now, and people only had to look at what came out of Frankfort this last period, to understand that anything we've won is only as safe as our ability to hold it safe,” said Carla Wallace, longtime community organizer and Fairness Campaign co-founder.

Many of those activists from a quarter century ago are still engaged in the work alongside new generations of those looking to expand the rights of the queer community. Activism work has since moved 24 communities to add similar anti-discrimination laws to their books, covering only about one-third of Kentucky’s population, said Chris Hartman, executive director of the Fairness Campaign.

Even with major victories for the community, from the expansion of local hate crime laws, the striking of state anti-sodomy laws, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015, activists say there’s much work to be done.

A slow build to expanded protections

When Wallace helped found the Fairness Campaign in 1991, she knew the effort to expand civil rights protections would take a broad base of support.

Wallace recalls the group making a key decision to press the issue through a variety of strategies that would get people across Louisville talking and hold politicians’ feet to the flames.

“We need to force this community into a conversation about whether or not the humanity of lesbian and gay people matters,” Wallace recalls thinking at the time. “Should we be fired just because of who we are? Should we be kicked out of a restaurant? Should we be denied housing?”

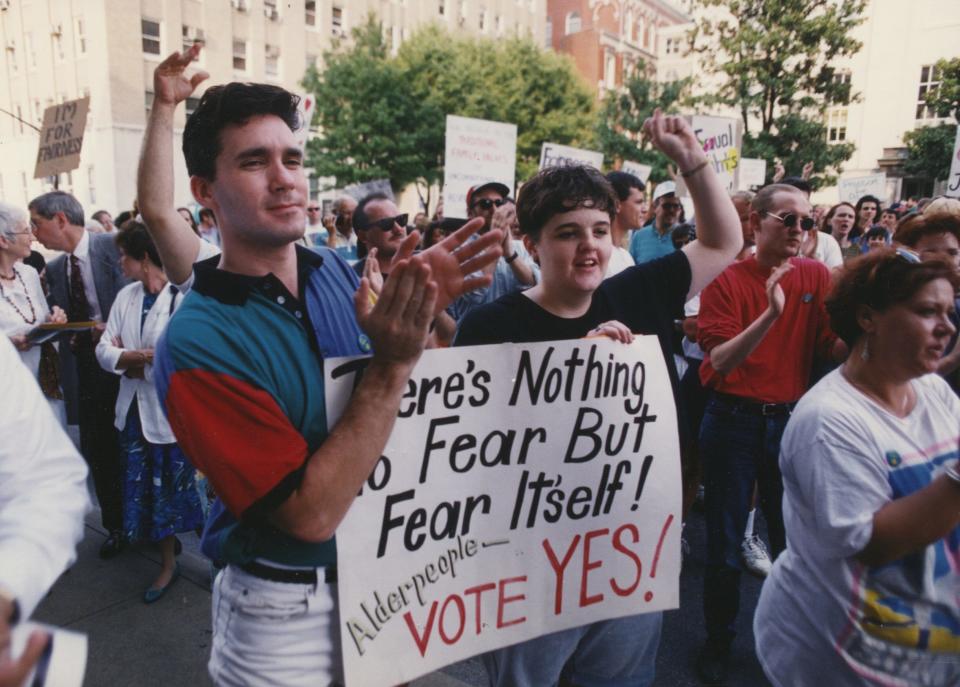

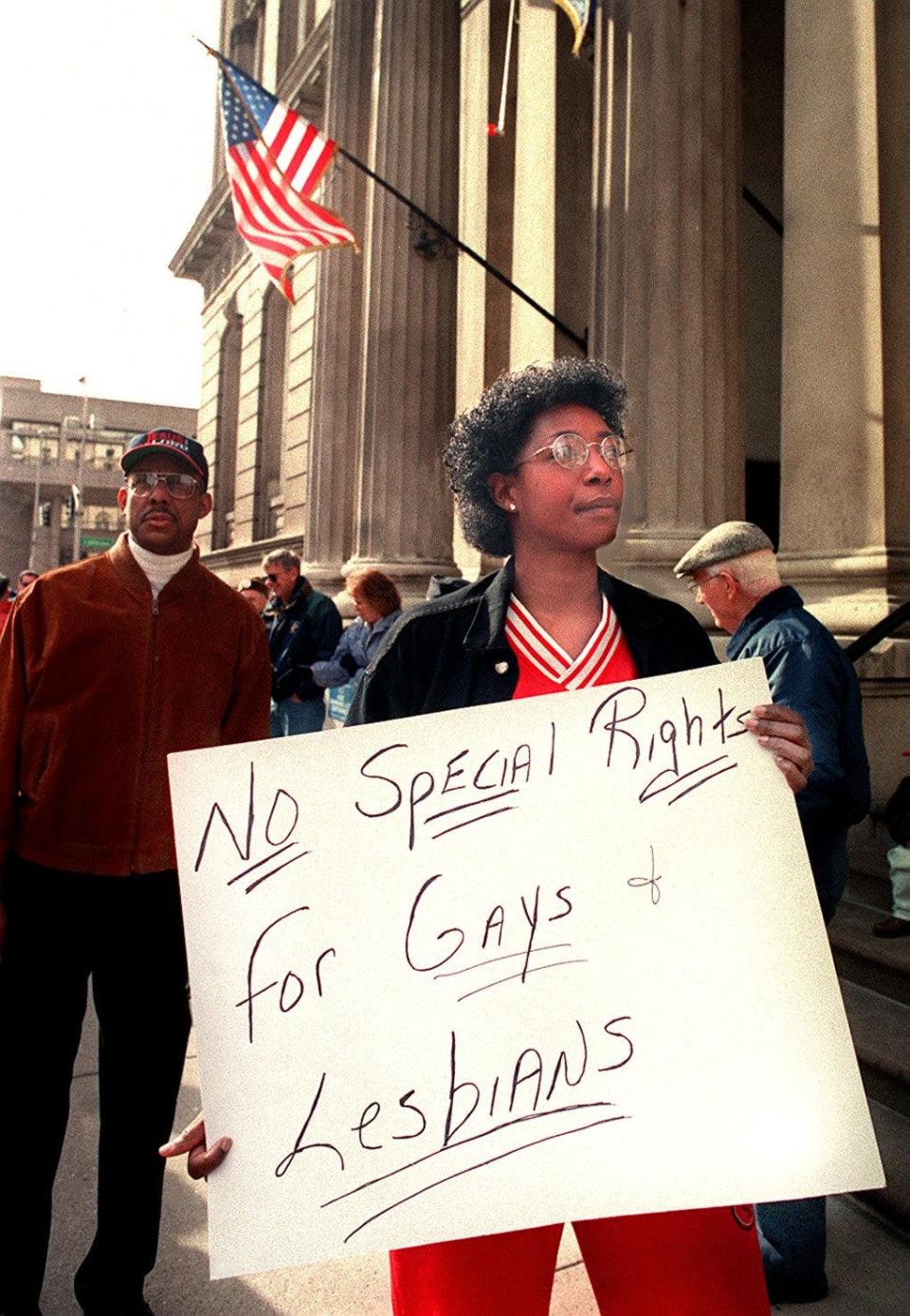

Organizers worked to frame the effort not as a push for special rights but for the rights already enjoyed by the majority of Louisvillians.

Groundwork was laid a few years earlier when a coalition of activists, the Greater Louisville Human Rights Coalition, lobbied the Louisville-Jefferson County Human Relations Commission to recommend the then-separate city and county governments add sexual orientation to its anti-discrimination laws.

The rights commission voted 13-5 to recommend the amendment to the Board of Aldermen. In 1991, the newly formed Fairness Campaign advanced the cause to the board, where the measure languished in committee before an unsuccessful vote in 1992.

Votes in 1995 and 1997 met similar fates.

Success, viewed that way, was elusive. But organizers were convinced they were developing something that would last.

“We built into the campaign a broad definition of winning,” Wallace said. “We talked about winning the vote, but we also said winning is more people understanding the issue, more people joining us, more people coming out, more people becoming activists and willing to speak at city hall … It hurt every time. Don't get me wrong. But we held the hurt within the context of knowing that we would win.”

The campaign worked on efforts big and small to push the dial toward acceptance in the face of opposition that ranged from questioning the necessity of an amended ordinance to religious condemnation of the LGBTQ+ community.

There were outreach nights at local gay bars. Fundraisers. Mailers. Door-to-door canvassing. Yard sign campaigns. Public demonstrations. One-on-one and small group meetings with elected officials, community groups and businesses.

The campaign launched “Alderwatch,” sit-ins of Board of Aldermen meetings where supporters would show local politicians their support of the Fairness Ordinance. Theme nights, including Catholics for fairness and family night, were meant to show the diversity of the coalition.

Fairness rallied faith leaders to form their own organization, Religious Leaders for Fairness, to show the faith community wasn’t a monolith dead set against gay rights.

They leaned on slogans such as “Fairness … No more, no less” and “Fairness does a city good.”

The organization also created a “friends of fairness” list, comprised of unions, small businesses, faith groups, and community organizations, among others.

“In the early '90s, people were so nervous, even groups that you would never guess would be nervous to talk about this issue were like, ‘Oh, we're not sure. This might be controversial,’” Wallace said. “But we knew that had to happen, that you cannot move from point A to point D without people going through a journey of transformation, and that was our work, community education.”

And, at times, Fairness supporters tried humor.

In 1992, when supporters sought the Board of Aldermen to schedule a hearing to take up the ordinance, supporters held “I want a date” signs at city hall.

When then-aldermanic president Steve Magre said the measure didn’t have a “snowball’s chance” of passing, as the Courier Journal reported in 1997, some fairness supporters took it upon themselves to follow Magre around city hall ― in a snowman costume.

Magre told the Courier Journal in 2019 that his vote in support of the ordinance in 1999, after years of opposing the measure, may have been the most important in his 23-year board tenure.

“Even if you only have one complaint a year, it’s a good law,” he said at the time. “I made the right vote.”

Building support with real-life stories and

Personal stories and political pressure worked to slowly move the needle.

In 1991, the Fairness Campaign launched a political action committee, the Committee for Fairness and Individual Rights, making it clear the organization intended to leverage the power of the polls.

Influence took time to build, Wallace recalled.

“And at first, no politician wanted our endorsement. ‘Please don't endorse,’ they'd say,” she said, laughing.

A poll conducted by the Courier Journal in early 1992 suggested just how much work the ordinance supporters had before them.

Forty-four percent of those polled said they wouldn’t want “homosexuals” as neighbors. While this was an improvement from the 51% who gave that answer in a 1990 poll, it was still decisively the most negative response of the 10 groups measured, save for “members of a religious cult” at 63%.

But as public opinion on gay rights slowly shifted in the 1990s, a vote for the ordinance seemed less risky.

The “neighbor” question showed 56% in support by 1996 and, in the same poll, 65% of respondents were in support of an ordinance protecting gays and lesbians from housing and employment discrimination, the Courier Journal reported at the time.

"What it was really about is that (politicians) were afraid politically that there wasn't enough support, and that's why we had to show them ... the people in their districts were supportive, and we would bring those people into their rooms, and pressure, pressure, pressure,” Wallace said. “And we ran people against them ... That helps someone change their mind.”

Political activism ran alongside personal narratives and testimony.

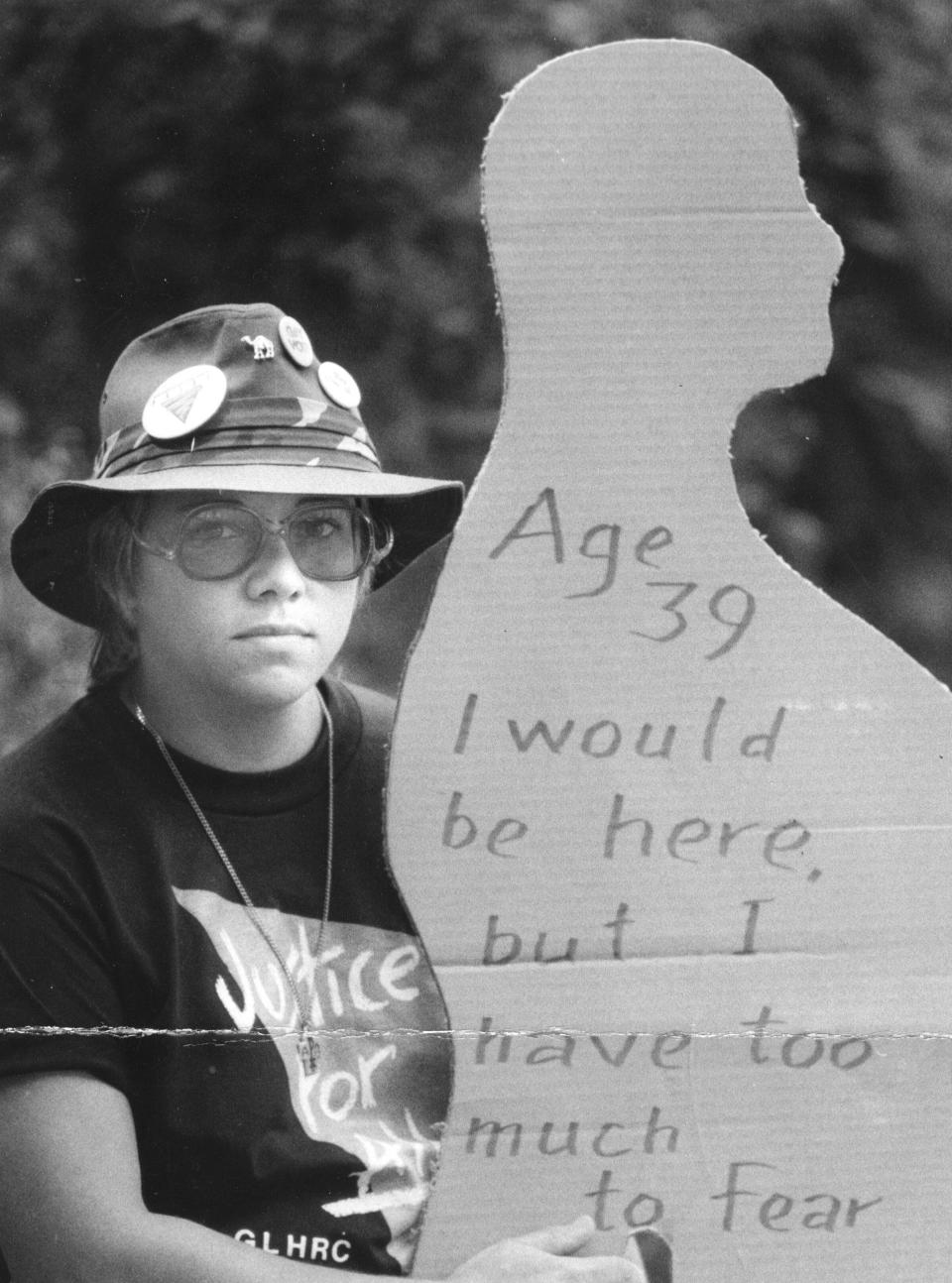

To counter the argument that such discrimination wasn’t happening, Fairness tracked reported discrimination incidents and solicited real-life stories. But speaking out when there was potentially much to lose was a tough sell for some.

In testimony before the Human Relations Commission in the mid-1980s, some people spoke about the discrimination they faced using only their first name while others testified from behind screens to shield their identity, fearing personal or professional ramifications.

Just months before the successful vote, Louisvillian Alicia Pedreira was fired from her job at Kentucky Baptist Homes for Children after a picture of her wearing a shirt that read “Isle of Lesbos” was entered without her knowledge in a photo contest at the Kentucky State Fair.

And while exceptions in Louisville's ordinance for religious institutions and religiously affiliated organizations meant Pedreira wouldn’t have been protected, her case garnered much publicity and public sympathy.

“The reality is, if somebody came forward and testified, they could be marked for the next job, you know, to not get it or for their family to say, ‘Don't come back home tonight,’” Wallace said. “People took tremendous risk getting involved.”

When Moten, who was let go from her day care job, was asked if she’d share her story, she set her shyness aside in hopes her words would be of help.

“I knew there was people out there that couldn't or weren’t in a place or position to do it,” she said. “Even though I was very nervous, I was like, ‘Well, maybe this will be able to help someone else somewhere and give them the courage to … feel like they're not alone.'"

Choosing a broader, intersectional approach to fairness

As the 1990s went on, organizers decided they would push not only for the addition of sexual orientation to the city’s anti-discrimination laws but also gender identity, referring to a person’s innate sense of gender that may or may not be the same as their sex assigned at birth.

Transgender activists helped push the Fairness Campaign to be more inclusive in its pursuits.

Dozens of other cities had already passed anti-discrimination laws for gays and lesbians but few had done so for transgender people.

“When we would go to conferences they would say, ‘Oh, no, you should lose the gender identity. You're not gonna be able to win that way,’” Wallace recalls. “We are going through the doors together. We are not leaving people behind.”

Alexander Griggs, a transmasculine man and community outreach coordinator at the Fairness Campaign, said the organization was listening to Black transgender people at a time when they were not being heard in many spaces.

“The leaders of Fairness, the founders of Fairness, refused to move forward without being inclusive of that,” he said. “And that's what really touched me, and that's what really spoke to me, and that's why I feel comfortable with this organization.”

Griggs' past professional experience in the therapy realm and his transition journey led him to his current role.

“It is still difficult for queer and trans people to be able to articulate the oppression they face,” Griggs said. “And because of that, it is really easy for people in power to disempower queer and trans people. So they do need protection from people who have misguided ideas about what it means to be queer and or trans.”

At the same time the Fairness Campaign was working to secure protections for the queer community, it was also working on racial justice efforts, including speaking out against police violence.

“We decided, unlike most places in the country, that we needed to bring an intersectional vision, which meant we're going to talk about racial justice and we're going to talk about economic justice, that this is all interconnected,” Wallace said. “Because the reality is for a Black gay man who is low income, what part of himself do we tell him is not part of this campaign? Bring your gay self, but don't bring your Black self or your poor self? No. We're gonna connect the issues, and we're gonna fight for all of it.”

Fairness work is 'as needed today as it was back then'

The Louisville Metro Human Relations Commission receives and investigates discrimination reports regarding sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as sex, race and disability, among others.

Between 2006 and 2021, the commission received an average of 10 complaints each year tied to sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination, commission data shows, and recorded monetary and non-monetary settlements for those discriminated against.

“There has been significant strides made, and we are definitely grateful for the shoulders on which we stand,” Griggs said. “A law being passed is not going to ensure that people follow it. We still have to struggle today, unfortunately. And Fairness is as needed today as it was back then."

Hartman, of the Fairness Campaign, said despite the rapid rising in favorable public polling on gay marriage and an increase in mainstream representation of the queer community, protections for queer individuals are under threat.

"The minute marriage happened, folks thought the movement was over, and you would have thought that by how some folks in the LGBTQ movement moved as well,” Hartman said.

He said securing same-sex marriage nationally hasn’t eliminated other issues faced by the community, particularly transgender individuals.

“And so there has been a difficult sort of re-education of the need for the movement to keep going,” Hartman said. “Now, in the past few years, the really vitriolic and harmful anti-trans rhetoric has made people much more acutely aware that the fight is not over.”

Proposals for a statewide fairness ordinance have failed to gain much traction for more than two decades despite a growing number of communities in Kentucky that have adopted expanded protections.

With a Republican supermajority in the legislature, Hartman said the organization he leads is most often playing defense and not able to make progressive headway.

“Before the tenor turned, when we were really banging out fairness ordinances in the (2010s) and the legislature looked different, we had hope,” he said. “We were building intentional, meaningful relationships with conservative lawmakers, and we still are where we can. But the reality is that Kentucky is no longer poised to, maybe even within the next decade, adopt a statewide fairness law.”

Still, Griggs thinks back to earlier this year at the Fairness Campaign's annual rally and lobby day in Frankfort. He remembers the energy in the halls of the Capitol and how the cheers of many supporters seemed to shake the marble walls.

"Bigotry doesn't die out,” Griggs said. “Time doesn't change hearts and minds. People do.”

Reach growth and development reporter Matthew Glowicki at mglowicki@courier-journal.com or 502-582-4000.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville's Fairness Ordinance against LGBTQ+ discrimination turns 25