One VP Contender Will Give Kamala Harris Her Best Chance With Swing Voters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kamala Harris has one job: Persuading currently undecided, indifferent, or loosely Trump-attached voters in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin to vote for her rather than Donald Trump (or Robert F. “Brain Worm” Kennedy Jr.).

So what will change these people’s minds? Well, that is the $10 billion question. But if they’re like other swing voters who’ve been surveyed and focus-grouped and interviewed in the past, the answer is something like: They want to vote for someone who isn’t too partisan but also isn’t necessarily in the center of every issue—lefty economic ideas do fine with them—and who seems like someone you could have a beer with but who also possesses a certain presidential dignity and vitality. Someone strong but unifying, as well as practical and possessing an intrinsic ability to improve the economy.

The top priority for Harris is convincing people that she is that person herself, of course, with her own words and advertisements. But she also gets to pick a vice presidential nominee—and according to some of the political-science research into the matter, that choice will likely be more important as a signal about herself than as a play to win any given state.

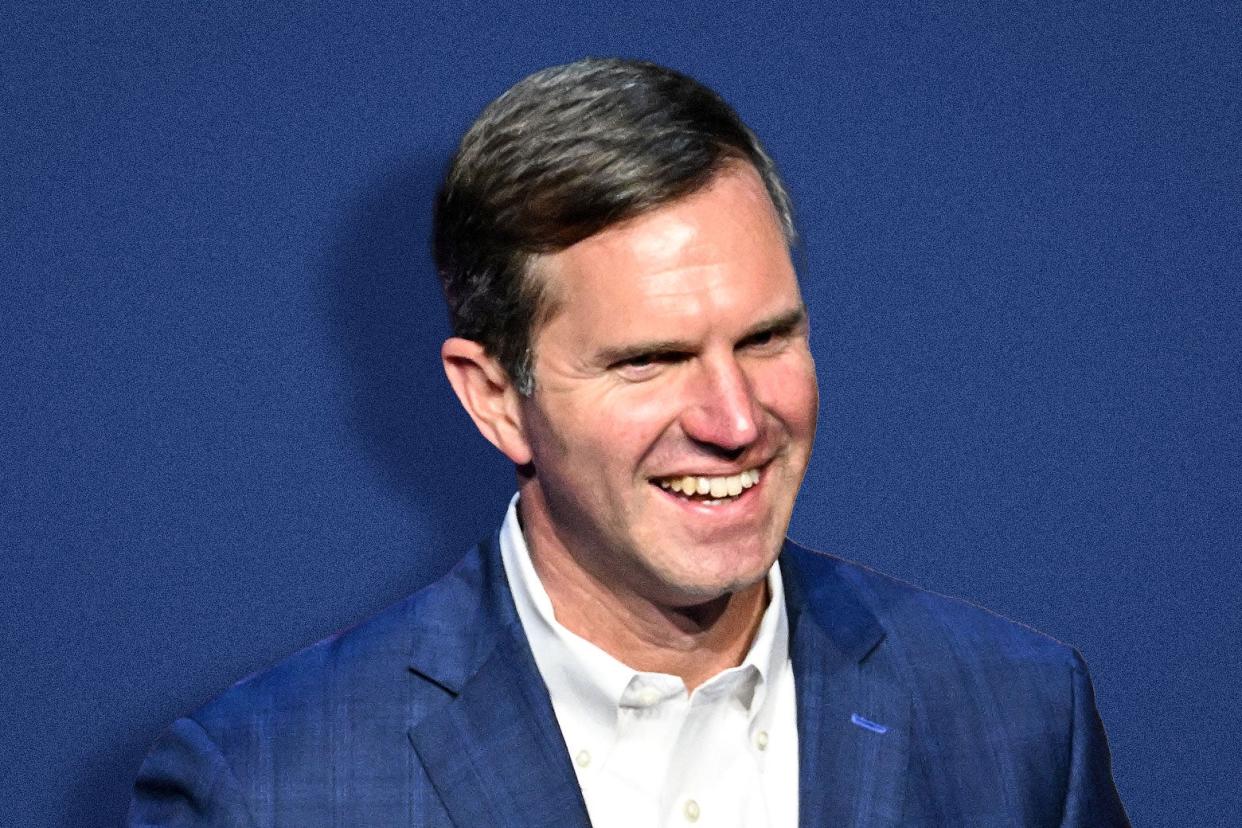

With this in mind, the choice is clear: She should select Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear as her running mate.

The most important thing to know about Beshear—and the only thing Harris would really need voters to know about him—is easy to explain. He is, despite being a Democrat, popular in Kentucky, a state that Donald Trump won by 26 points in 2020. (Beshear won reelection in 2023 by 5 points, and his approval rating in Morning Consult’s latest data was 67 percent.) That would be the purpose of this pick: associating herself with one of the rare politicians in the contemporary U.S. who can honestly say they’ve been a uniter rather than a divider.

Nearly as important, though, is how Beshear has done it. Some Democrats in red states—West Virginia’s Joe Manchin comes to mind—make their reputation by picking high-profile fights with national party leaders and denouncing certain ideas as too liberal. There’s a strong utilitarian argument that this is a good thing for the party overall: It needs senators from West Virginia and Montana and Arizona however it can get them, and given the Republican assault on election administration, it needs as many Democrats in swing-state governors’ mansions as it can get too. But those figures are less than ideal vice presidential choices because they’ve alienated groups whose participation in the presidential campaign is essential. If Harris chose Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly, it might bother the major unions; if she chose Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, it would put off critics of Israel’s conduct in Gaza.

Beshear has not made—or has not been forced to make—any of these kinds of friendly-fire compromises in order to prove his independence. For one, he has the good fortune of being the son of another former governor, Steve Beshear, who was also popular in the state despite being a Democrat. Republicans hold a supermajority in the Kentucky Legislature, which means that they can override (Andy) Beshear’s vetoes of legislation. Because he literally can’t stop Republican ideas from being turned into law if they’re popular enough, he doesn’t have to make as many tough calls as someone in a more evenly split state might.

That said, he has taken liberal stands on policy when less confident Democrats might have gone wobbly. He vetoed a bill that would have banned minors from receiving gender-affirming care, describing it as an attack on “children of God” that would limit parents’ freedom to make medical choices. (The veto was overridden.) He made the protection of Kentucky’s (limited) abortion rights a central issue in his reelection campaign, although he does support what he described as “reasonable restrictions on late-term abortions.”

There’s more. Beshear rejected calls to impose “work restrictions” on Medicaid eligibility, restored voting rights to 175,000 ex-felons through executive order, has been unwavering in opposing the diversion of public education funds to charter schools, and publicly declined the Trump administration’s offer to stop resettling refugees in Kentucky. He also walked a United Automobile Workers picket line in 2023, which is not the easiest gesture to make in a state whose economy is heavily affected by automakers’ decisions about where to locate manufacturing plants. (He seems to be doing well on that front too, at least according to Business Facilities magazine and Site Selection magazine.)

You might be asking: OK, sure, but is he good on TV? It’s a subjective question, but if Beshear’s appearances in recent weeks and the tape from one of his 2023 debates are any indication, he’s good enough. He’s perhaps not the loosest presence, but he does a smooth job of moving discussions toward the points he wants to talk about without being evasive and shows command of details without getting lost in them. (His success in Kentucky, local observers say, is in part attributable to his reassuring presence on camera during COVID and in the wake of a series of natural disasters that have befallen the state.)

The debate was held during the peak of Ron DeSantis–style attacks on supposed LGBTQ indoctrination of students by public-school teachers and librarians. Beshear prepared a deceptively plainspoken deflection. “I’ve heard it over and over across the state,” he said when the issue of inappropriate instruction was brought up. “People’s kids aren’t being exposed to things through the classroom or through libraries—they’re being exposed to them through my opponent’s commercials.” A solid zinger but also, if you’ll notice, a good way to avoid having to discuss what teachers in conservative Kentucky should be telling middle-school students about human sexuality. (You might call it a “Teachers Are Making Our Children Gay by Using Inclusion Policies as a Trojan Horse for Their Diabolical Grooming Vs. No They Aren’t” approach.)

When it comes to being sensible and down-to-earth, Beshear walks the walk, and he talks the talk. His opening debate statement quoted from the Book of Psalms, then listed the construction of a Margaritaville as one of the signature accomplishments of his term in office. What else could Kamala Harris want?