Pennsylvania Supreme Court to weigh life sentences for felony murder

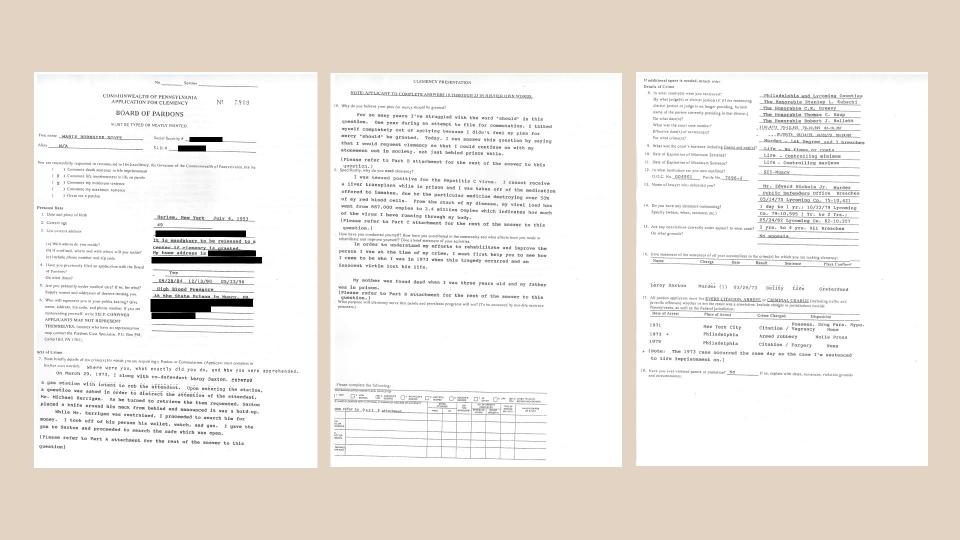

A collage of images and documents from Marie Scott's archives. Scott, now 70, has been in prison since she was 19. (Courtesy of Ellen Melchiondo, arranged by Miranda Jeyaretnam/PublicSource)

Marie “Mechie” Scott is like most 70-year-olds. Her cheeks are dotted with age spots, her cornrows are graying and her forehead crinkles when she breaks into a laugh. She moves slowly, uses a wheelchair and has chronic back pain that makes it excruciating to walk, cough or lie on her side. She paints, sings and collects crocheted animals.

Unlike most 70-year-olds, though, Scott has spent her entire adulthood behind bars at the State Correctional Institution in Muncy, Lycoming County. Without some kind of intervention — a change in the law or a court ruling in a case she has no hand in — she will die in prison.

When Scott was 19, she was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for felony murder. Under the felony murder doctrine, a person accused of committing a felony can be charged with murder for a death that occurs during the felony, even if the defendant was not the killer and had no intent to kill. In Pennsylvania, conviction comes with a mandatory sentence of life without parole, one of the most severe renderings of the felony murder rule in the country.

Scott’s fate could now hinge on a case that originated in Allegheny County. This fall, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court will hear a criminal appeal from Derek Lee, a Penn Hills man half Scott’s age, on the grounds that mandatory life without parole for felony murder constitutes cruel punishment, violating the Pennsylvania constitution.

Lee, now 36, was convicted of felony murder in 2016. He participated in a robbery in 2014 when his accomplice fatally shot the homeowner. In February, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed to hear Lee’s appeal. Bret Grote and Quinn Cozzens, the Abolitionist Law Center co-counsel on the case who also brought Scott’s lawsuit, expect that oral arguments will be heard in October.

Across Pennsylvania, 1,131 people are currently incarcerated for felony murder. A favorable decision for Lee won’t guarantee release for the rest of them, including Scott. It’s unlikely to lead to fulfillment of any of her longtime dreams, like running a taco truck. It might give her a chance to linger in her daughter’s arms, or at her son’s grave.

Saved, then ensnared, by the silver gun

On March 29, 1973, in Philadelphia, 19-year-old Scott, high on sedative pills, committed a string of robberies with her boyfriend, Leroy Saxton. While attempting to rob a gas station, Saxton shot the attendant, Michael Kerrigan.

Saxton, who was 16, was convicted of murder. Because he was a juvenile at the time of his crime, he was later resentenced and released on parole in 2020.

Scott’s reflections on her crime have remained consistent over several decades. In five interviews with PublicSource over 13 months, and in letters sent to friends and public writing over many years, she expressed remorse and regret over her role in killing Kerrigan. “I am guilty, guilty, guilty! … GOD knows that today I would switch places with my victim in a heartbeat because I am so very, very sorry,” Scott wrote in a 2019 letter to the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons. Scott has also communicated with Kerrigan’s granddaughter.

Scott was raised by her aunt after her mother died and her father was incarcerated. Abused during childhood, she had her first child when she was 15 and rough sleeping in New York. She became a “severe codependent,” she said, and was willing to do anything for anyone who showed her love.

She had just moved to Philadelphia and started working as a manager at a restaurant when two men attempted to rob her at her work. Saxton stepped in, pulling out a silver-colored gun — the same gun later used to shoot Kerrigan, she recalled. “I felt I owed him my life,” Scott wrote in a letter to Grote. “I did not just wake up one day and decide to go on a spree of robberies with another juvenile delinquent.”

Scott’s difficult background is typical of women serving life sentences, according to Celeste Trusty, the Pennsylvania director at Families Against Mandatory Minimums. Particularly during the tough-on-crime decades of the 1970s to 1990s, Trusty said, courts often did not recognize abuse, trafficking or trauma as conditions that led to criminal involvement.

Life without parole ‘a pointless act of cruelty’?

In most states, life-without-parole sentences were a late-20th century innovation, according to Bruce Ledewitz, a professor of constitutional law at Duquesne University; most states had parole eligibility for life sentences, then legislators decided that “certain categories of cases” would be ineligible for parole.

Pennsylvania courts must state minimum and maximum terms of imprisonment when issuing a sentence, with the minimum being half of the maximum. A person becomes eligible for parole upon completing the minimum sentence and must be released upon serving the maximum sentence, even if parole is not granted.

If, for example, a defendant is sentenced to serve 20 years in prison, they would be eligible for parole halfway through. Since life sentences do not follow a term of years, Pennsylvania “stumbled” onto what advocates call death by incarceration, Ledewitz said.

Pennsylvania’s original parole law, passed in 1911, made no exception for life sentences. A 1939 governor’s commission on overhauling the commonwealth’s parole system was “the precipitating event that evolved into a ‘life-means-life’ millstone that continues to crush those serving terms of life imprisonment,” wrote Jon Yount, a jailhouse lawyer serving a life sentence, in a 2004 history of the punishment.

Yount, who advocated for prisoners’ rights until his death in 2012, noted that the commission’s recommendations created ambiguity, establishing broad authority to parole all people sentenced to imprisonment and a contradictory exception for life imprisonment. The words “life in prison without parole” weren’t included in state law until 1982, when it was added as the punishment for “arson murder.”

Pennsylvania law treated felony murder as harshly as intentional murder, allowing for the death penalty, until 1974 when the state legislature rewrote parts of the Crimes Code in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1972 ruling in Furman v. Georgia. In that case, the justices ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional when applied in a capricious manner.

Felony murder became second degree murder and capital punishment was no longer an option, but life imprisonment remained as the only, mandatory, sentence.

Pennsylvania has not executed a death row prisoner since 1999 and Gov. Josh Shapiro last year extended a moratorium on executions that Gov. Tom Wolf established in 2015.

That makes life without parole, effectively, the most severe sentence that Pennsylvania imposes, said Nazgol Ghandnoosh, co-director of research at The Sentencing Project, an anti-incarceration group. It also means that the penalty for first degree murder — a premeditated, intentional killing — is the same as that for second degree murder, including felony murder.

“I think anyone who’s familiar with the law would recognize that’s a less serious offense than an intentional murder,” Ghandnoosh said, noting that the intent of the felony murder rule is to punish a person more severely for a felony because they were involved in a crime that led to the death of another.

“The question that we have to ask society, that the Pennsylvania courts are being asked to answer is, how much more serious is it? Should that crime be treated as if it were an intentional killing?” Ghandnoosh said.

In 2020, Scott was the lead plaintiff, among six serving life sentences for felony murder, in an unprecedented constitutional challenge. The lawsuit, filed in Commonwealth Court by the Abolitionist Law Center, Amistad Law Project and the Center for Constitutional Rights, argued that mandatory life without parole for those who did not kill or intend to kill violates the state constitution.

But the case was dismissed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 2022 on grounds that it was improperly filed as a civil lawsuit and that Commonwealth Court lacked jurisdiction. The court found the plaintiffs could still challenge the legality of their sentences after exhausting the appeals process, but those claims must be filed through criminal court.

Lee’s case, which was filed in May 2022 as a criminal appeal, addresses that issue.

Lee’s lawsuit challenges mandatory life without parole based on the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, and the state Constitution’s bar on cruel punishment.

Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala’s office, which prosecuted Lee, did not respond to requests for comment on the case.

Constitutional law scholars, along with other experts and elected leaders including Shapiro, support Lee’s case, arguing that life without parole for felony murder is excessive and does little to accomplish the goals of punishment.

Advocates have filed more than a dozen “friend of the court briefs,” in support of the appeal. Their position hinges on the Supreme Court’s long-standing recognition that the most severe punishments may be disproportionately harsh and violate the Eighth Amendment when imposed on people convicted of less serious crimes or who are less culpable for an offense.

Lee falls into the latter category because he did not kill or have the intent to kill, said Seton Hall Law School professor Jenny-Brooke Condon, who authored a brief in support of Lee’s appeal signed by more than a dozen Eighth Amendment scholars.

In a 1982 death penalty case with parallels to the Lee and Scott cases, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of a Florida man, Earl Enmund, who was sentenced to death along with his co-defendants, who robbed and killed an elderly couple in their farmhouse.

Executing Enmund, who waited in a car while the murders happened, would violate the Eighth and Fourteenth amendments because his culpability was less than that of the killers, Justice Byron White wrote for the 5-4 majority.

Enmund’s punishment must be “tailored to his personal responsibility and moral guilt,” White wrote.

Expanding on that principle in Miller v. Alabama, the court ruled that mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional.

The decision centered on science showing teenagers and young adults are more susceptible to impulsivity, poor decision making and peer pressure. But crucially for Lee’s appeal, Condon said, the court also recognized that mandatory life imprisonment without parole is one of the most extreme sentences available.

“When you put those two pieces together, it sort of demands that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court look carefully at whether or not this kind of sentence, which is so excessive and out of the norm in Pennsylvania, really is an outlier,” Condon said.

While the Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, the corresponding section of Pennsylvania’s Constitution requires only that a punishment be cruel to be impermissible.

“Even if the Eighth Amendment doesn’t quite extend far enough,” said Cozzens, “the Pennsylvania Constitution should be read independently to provide more protections than the federal Constitution would.”

A number of states have revised their felony murder rules and moved away from automatic life without parole sentences, Condon said.

Ledewitz also pointed to a significant turn in public opinion. “If we were talking about 30 years ago at the height of the anti-crime public opinion, there’d be no chance that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is finding it unconstitutional,” but public opinion has shifted to “questioning the wisdom of life without parole.”

In its analysis, the state Supreme Court will consider how life without parole fits into the justice system’s sentencing goals: deterrence, retribution for victims, public safety and rehabilitation, said Jill McCorkel, a professor of sociology and criminology at Villanova University.

“On all those criteria, it just doesn’t make sense,” McCorkel said.

In addition to the illogical notion that a harsh sentence will deter someone from committing a crime they don’t intend, decades of research on people sentenced to life without parole shows that they age out of criminal behavior by their 30s and 40s, said Ghandnoosh, of the Sentencing Project.

Felony murder sentences raise questions of equity, advocates say. According to an analysis by the Felony Murder Reporting Project, a data project at Yale University, 71% of those incarcerated in Pennsylvania for felony murder are Black with even higher rates in Allegheny County and Philadelphia, despite Black people making up just 12% of the population. Both Scott and Lee are Black.

The project found that more than 3% of felony murder lifers are women.

“I think that there’s a way in which women’s poverty and women’s vulnerability to street violence as well as to intimate partner violence really ensnares them in a way that I don’t think anyone intended,” McCorkel said, noting that women may be coerced into participating in a crime and be unwilling to testify against a partner.

Few get out alive

After half a century in prison, Scott has stopped celebrating her birthday, July 4. Most years, her friends try to throw her a surprise party or time it to coincide with the holiday celebrations. But Scott doesn’t see a reason to celebrate another day behind bars.

You have to forgive in this life ... I don’t believe that someone should be defined by the worst day of their life.

– Nancy Leichter

Scott has spent her time trying to make amends and make something of her life. Her resume spans two pages: she has written a play, earned a culinary degree and crafted legislative bills in support of children of crime victims and children of incarcerated parents. She signs off on some letters to friends and reporters with “In the struggle.”

While incarcerated, she became pregnant with another child, a daughter whom she nicknamed Hope, and mourned the death of her son. When she got the call about the motorcycle accident that killed him, she couldn’t stop screaming — or recalling her role in the Kerrigan family’s loss.

Most people convicted of felony murder are young at the time of their crime. The median age in Pennsylvania at the time of admission for felony murder convictions is 25, eight years younger than the median age for all crimes.

The opposite is true of overall prison demographics: More than 27% of people incarcerated in Pennsylvania’s prisons are over the age of 50. Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections pays a high price for their medical care — $34 million annually for medications to treat chronic health conditions.

Families for victims urge mercy, not revenge

“There’s got to be a place for mercy in our system,” said Trusty, of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “It can’t just be about punishment.”

Some victims and their loved ones agree. Thirteen people came together as family members and loved ones of murder victims to submit an amicus brief in support of Lee’s appeal.

Laurie MacDonald, president and CEO of the Center for Victims, said that while victims’ stances on extreme sentencing are not monolithic, many of the people the center works with recognize that life sentences impact more than just the incarcerated individual.

“I’ve been amazed at the number of victims who show an enormous amount of grace when it comes to punishment because they recognize human tragedy and frailty,” said John Rago, a law professor at Duquesne University and the board president of the Center for Victims.

Nancy Leichter is one of those people. Leichter’s father died in 1980 when he had a heart attack during an armed carjacking. Two out of the three perpetrators, brothers Reid, 19, and Wyatt Evans, 18, were sentenced to life without parole for felony murder. The third perpetrator, Marc Blackwell, was convicted of third-degree murder, and released in 2018 on parole. The Evans brothers were also plaintiffs in the 2020 lawsuit with Scott.

Blackwell held a gun to Leichter’s father while the Evans brothers drove his car. Leichter’s father pleaded: He was a heart patient, please let him out of the car, Leichter said. They dropped him off at a phone booth and drove off. He died three hours later.

Leichter recalled that her father’s death devastated her family. At 68 years old, he had just retired. He played golf, he was an artist and a sculptor. “People say you get closure when [the perpetrators] get sentenced, but we were all in such shock,” Leichter said. “For us, it was about our grief — I didn’t care about them, I only cared about our loss.”

When Blackwell was released in 2018, however, Leichter started thinking more about the Evans brothers’ culpability. “I’m not the same as I was when I was 18,” Leichter said, and she didn’t believe they should spend the rest of their lives in prison when they hadn’t intended or expected for anyone to die.

“You have to forgive in this life,” said Leichter, echoing her mother’s teachings. “I don’t believe that someone should be defined by the worst day of their life.”

When Leichter learned that the Evans brothers had been denied commutations, she began actively campaigning for their release. She wrote op-eds and letters to the Board of Pardons and testified at their next commutation hearing. She believes that her testimony as a relation of a victim led to their release in 2022 after 40 years in prison.

She hadn’t met them face-to-face before — even during the hearing, which she attended via Zoom. After their release, they met, and the two men apologized to her. They went to a McDonald’s and she watched one of them try a smoothie for the first time.

“My closure came when they were released, when I met them, and I knew that they were back with their family.”

Dreams deferred

Lee’s mother, Betty Lee, imagines the day she sees her son outside again, for the first time in around a decade. He would get to hold his niece, who just turned one. Betty Lee would have a big cookout, but she’d leave the grilling to her son, who always said he made the best hamburgers in town. She wants to go to a beach together. They used to go to pools and water parks because he loved to swim as a kid, but they had never been to a beach.

Even if Lee wins, Scott won’t immediately be freed. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court would have to rule that mandatory life-without-parole for felony murder is unconstitutional and that the finding applies retroactively.

In a friend of the court brief on behalf of Shapiro’s office, General Counsel Jennifer Selber urged the court to find mandatory life without parole for felony murder in violation of the state Constitution, but cautioned against making the new rule retroactive. Doing so would place too great a strain on the legal system, the brief says.

Instead, the decision of how to implement the ruling for those already serving felony murder sentences should be left to the executive and legislative branches of the state government, the brief says.

Several pieces of legislation that could shift the outlook for people serving life sentences are pending in the General Assembly. State Sen. Sharif Street (D-Philadelphia), introduced Senate Bill 135 last year but it has sat for more than a year in the Republican-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee.

The bill would establish parole eligibility after 25 years for those convicted of second-degree murder, including felony murder, and 35 years for those convicted of first-degree murder.

Street said he believes there is bipartisan support for measures to address parole for felony murder directly and to provide compassionate release for geriatric prisoners serving life sentences.

“I certainly think there’s sufficient political will that if we get a vote, we can get this done,” Street said.

When the concept was originally introduced in a 2016 bill by state Rep. Jason Dawkins (D-Philadelphia), it would have allowed those serving life sentences to apply for parole after 15 years.

Felix Rosado, an advocate for sentencing reform who who was sentenced to life for first-degree murder in 1996 and received a pardon in 2022, said the minimum sentences in the current version of the bill track the minimum sentences for juveniles in a 2012 law passed after the Miller decision instead of relevant expertise, but have no basis in science.

“Legislators just pulled it out of the air. And now we’re stuck with it,” Rosado said.

State House Speaker Joanna McClinton is the prime sponsor of a bill to amend the state Constitution to make it easier to receive a pardon from the governor’s office. House Bill 1410 would eliminate the requirement for a unanimous vote from the Board of Pardons to receive a recommendation for clemency.

The board recommended commutation for 460 people serving life sentences between 1971 and 1994. After 1995, when Republican Gov. Tom Ridge altered the composition of the board of pardons and instituted the unanimous vote requirement, the number of recommendations dropped to into the single digits (or zero in the case of Gov. Tom Corbett’s administration) until Wolf took office.

Under now-U.S. Sen. John Fetterman’s leadership as lieutenant governor, the board sent 56 recommendations to the governor’s desk, of which Wolf granted 53. The proposed constitutional amendment would restore the requirement for a three-fifths vote to receive a recommendation of clemency that was in place before Ridge changed it.

The bill is awaiting final passage in the House, but the process of amending the state Constitution is arduous. The proposal must pass in the Senate before the end of 2024 and then pass both chambers again before the end of 2026. It would then go before voters in a ballot referendum.

Senate Majority Leader Joe Pittman (R-Indiana) said in a statement that legislative criminal justice reforms must prioritize safety and security. He noted that legislation to reform the state’s probation system, spearheaded by Sen. Lisa Baker (R-Luzerne) and championed by rapper Meek Mill, was signed into law in December.

“We remain open to conversations about ways to also reform parole in Pennsylvania, while ensuring individuals who are convicted of murder charges are appropriately held accountable for their actions against their victims, families, and society,” Pittman said in the statement.

If the state Supreme Court rules in Lee’s favor and makes the ruling applicable to people already serving life sentences, or if any of the legislation passes that would put parole or pardons within reach of lifers like Scott, she still would face months of litigation.

Inside, Scott has helped friends get their sentences overturned or shortened through legal research. She’s also watched several friends inside and outside of prison die.

She’s hopeful she may still gain freedom, though she may be too old to live out some of her dreams: opening a taco truck or getting her advanced paralegal license.

On May 10, Scott wrote with an update: She would be entering chemotherapy for stage 2 cancer.

“Nothing,” she added, “is gonna stop our plans, though.”

This story was fact-checked by Laura Turbay.

This story was produced in a partnership between the Pennsylvania Capital-Star and PublicSource.

(This article was updated at 7:30 a.m., Tuesday, June 4, 2024, to correct an error in the description of the process to amend the state constitution.)

The post Pennsylvania Supreme Court to weigh life sentences for felony murder appeared first on Pennsylvania Capital-Star.