Some planets 'death spiral' into their stars and scientists may now know why

Scientists may have discovered why the orbits of some planets decay, ultimately leaving these worlds to "death spiral" into their stars. This discovery may help astronomers spot which planets in star systems are doomed die a fiery death, and when.

Recent research had revealed that as many as one in 12 stars may have cannibalized one of their own planets, but what remained unknown is quite what caused these planets to plunge into their stellar parents in the first place. Now, however, an investigation by an international team of scientists has revealed the mechanism causing some planets to "take the plunge."

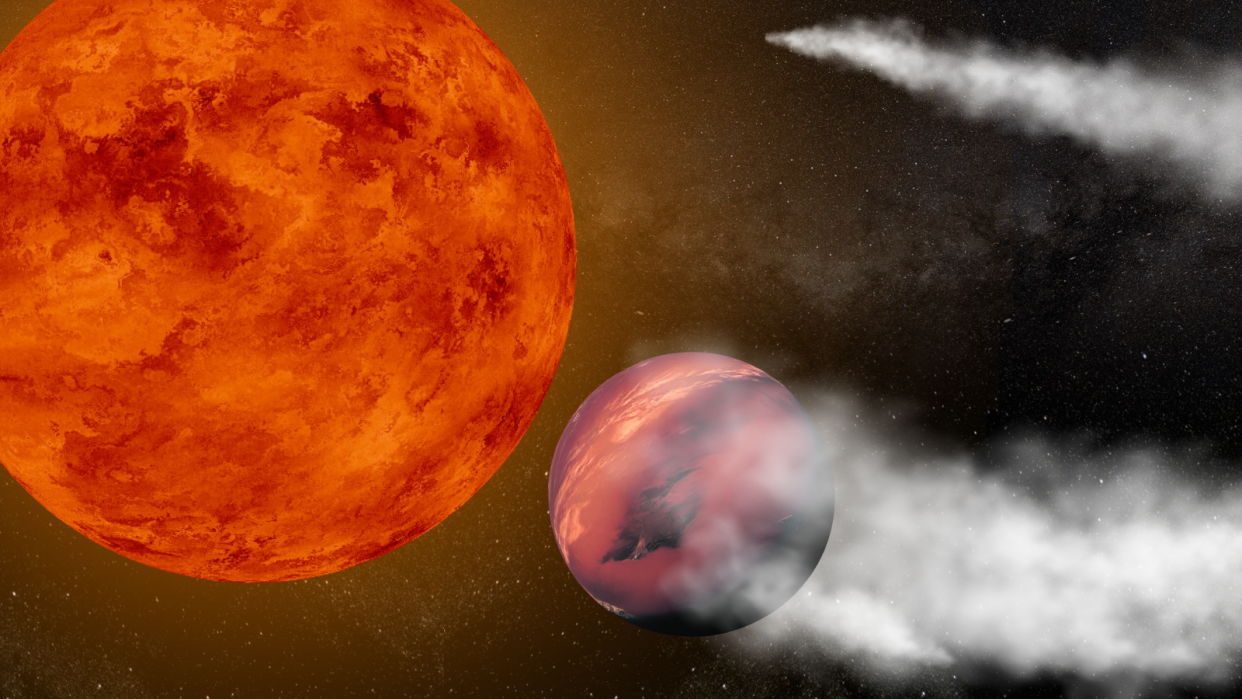

In particular, scientists concentrated on the decaying orbits of hot Jupiters, a class of planets that exist so close to their stars they are blisteringly hot and complete orbits in periods of a few Earth days to just a few Earth hours.

The team focused on a specific hot Jupiter called WASP-12b, located around 1,400 light years from Earth. As soon as 3 billion years from now, this planet could slam into its star. The team discovered that the magnetic field of the star WASP-12, which this planet circles, is dissipating gravitational energy, causing the orbit of this doomed planet to decay.

Related: 1 in 12 stars might have swallowed a planet

"Our study provides a new way — involving magnetic fields deep inside the star — for gravitational tides to act in extrasolar planetary systems, and which appears able to neatly explain the decaying orbit of WASP-12b," team member and Leeds University scientist Adrian Barker said in a statement. "It's exciting to have discovered a plausible solution to this mystery."

Sun-like stars making waves for doomed exoplanets

In arrangements between stars and hot Jupiters, both bodies are subjected to powerful tidal forces that transfer orbital energy from the planets to tidal waves within the star. When these waves dissipate, the net result is the planet has lost orbital energy. That causes the planet's orbit to decay, bringing it closer to the star.

Yet even this can't explain WASP-12 b's orbital decay, which will see it plunge into its yellow dwarf star in just a few years. Rather, the new research suggests another factor is at play; strong magnetic fields in WASP-12 seem to dissipate orbital energy pretty efficiently. This would also happen in other sun-like stars, the team says.

As the tidal waves within such stars move inward, they crash into magnetic fields and are themselves converted into magnetic waves that ripple outwards, eventually dissipating.

"What is really interesting about this mechanism is that it only starts after the star has reached a certain age. At the moment, the only planet we know for certain to be spiraling into its star — and in the far future, possibly being destroyed — is WASP-12b," Nils de Vries, research team member and a scientist at Leeds University, said in the statement. "With this new insight, we might actually be able to predict when certain planets will start that process, and our findings will help guide observational astronomers wanting to witness orbital decay."

Related Stories:

— Doomed egg-shaped exoplanet is death-spiraling into its star

— Scientists catch real-life Death Star devouring a planet in 1st-of-its-kind discovery

— Star blows giant exoplanet's atmosphere away, leaving massive tail in its wake

Of course, Barker and colleagues were indeed able to use their findings to estimate how quickly the orbits of hot-Jupiter planets around sun-like stars will decay. They then compared these results with recent observations.

They think some stars close to the sun may be good future targets in the hunt for hot Jupiter planets on decaying orbits. Finding these would help astronomers learn more about the magnetic mechanism that spells doom for some planets, and refine Barker and colleagues' timeline measurements even further.

The team's research is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.