Plankton: Why these tiny creatures are the 'building blocks of life in the sea'

This week at the Oceanarium, I was stopped short while explaining that the eggs from a crab hatch into larval stages and become plankton. The question that stopped me was, “What is plankton?”

Now, my husband has often ribbed me about being caught up in science speak and forgetting that not everyone knows what I am talking about. While I strive to explain things succinctly, sometimes I slip up.

So, what is plankton? NOAA states, “An organism is considered plankton if it is carried by tides and currents and cannot swim well enough to move against these forces.”

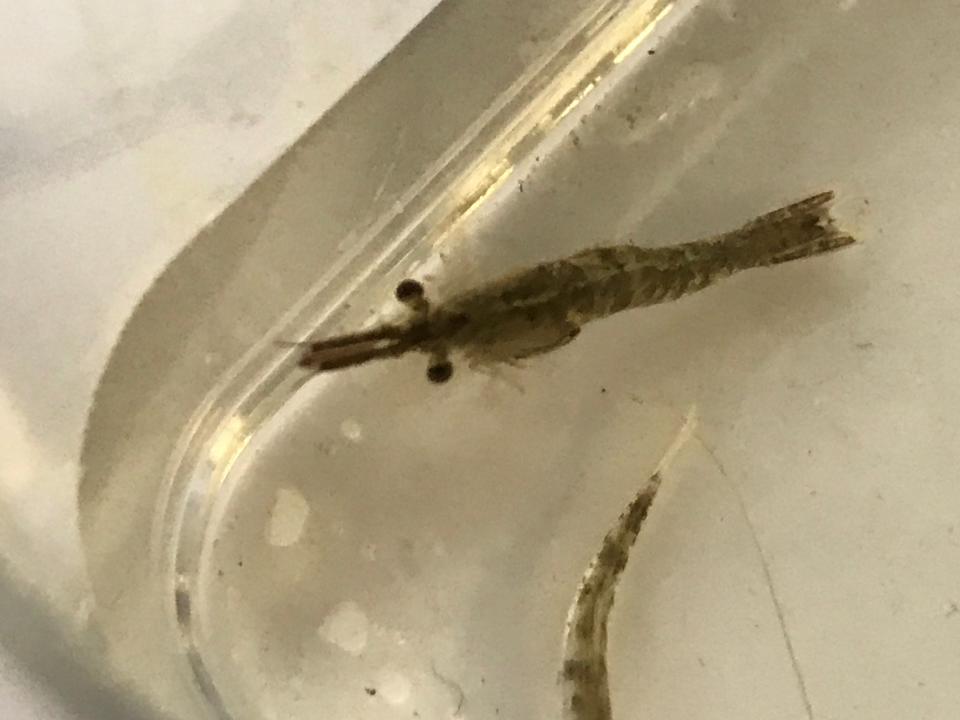

If you have ever glanced at a tidepool or seaweed floating at the tide line, you have probably noticed tiny things darting about. Some people describe them as baby shrimp or insect-like, both good descriptions. Plankton comes in all sizes and shapes, from microscopic to several inches. Some larger jellyfish are considered planktonic. Plankton are the building blocks of life in the sea. Everything depends on them.

Phytoplankton are microscopic plants that can be as small as one cell. They contain chlorophyll, which allows them to photosynthesize. Photosynthesis is the process by which plants make sugars (their food), and in doing so, they use carbon dioxide and release oxygen into the water.

Holy mola! Check out video of ocean sunfish spotted off Hampton Beach

Today, I was listening to the BBC news, and they were reporting that most of the world’s oxygen is produced by photosynthesis in the world’s oceans. I can honestly say I hadn’t thought about this recently, but it makes complete sense. Since phytoplankton need the sun’s rays to produce energy, they are usually found close to the surface of the water.

Now, zooplankton are animals. They feed on nutrients in the water, phytoplankton and other zooplankton.

The two major types of zooplankton we see in our tidepools here are crustaceans (in the same family as crabs and lobsters) called amphipods and isopods. Most of these are considered macroplankton due to their size (from ¾ of an inch to 8 inches). Amphipods look a little like tiny seahorses, or tiny shrimp swimming like sea horses. They are flattened side to side. Isopods look like those insects we see in the dirt as kids that we called pill bugs or roly polys. They are segmented and flattened from top to bottom. Both plankton play a huge role in keeping our ocean ecosystem healthy. Most zooplankton sink towards the bottom of the ocean during the day, and at night they migrate towards the surface and feed on phytoplankton. NOAA says this is considered the largest migration on Earth and can be seen from space!

More: Basking shark spotted off Hampton Beach: Check out the video

Most animals, both invertebrates (such as crustaceans like crabs, lobsters, and shrimp, and mollusks like clams, mussels, scallops, and snails) and vertebrates (including all bony fish), lay thousands of eggs at a time. These eggs hatch into larval stages, which make up a significant portion of the plankton in our oceans.

Most animals have several larval stages before they grow into something that looks like the adult animal they will become. With invertebrates, out of several thousand eggs, about 3 to 5 will live to be adults. The rest are part of the food chain. That is how the oceans work. To ensure the survival of their species, the marine animals lay thousands of eggs and as a byproduct, ensure survival of everything else by providing plankton for food.

We always have any number of plankton in our tanks at the Oceanarium, microscopic and macroscopic. You can observe amphipods hanging perpendicular in the water around the seaweed and isopods darting about. We monitor the females with eggs as they mature, and then, miraculously, their eggs hatch overnight, filling the tank with tiny juvenile amphipods.

My two junior biologists, James and PJ, brought in a few isopods from the tidepools a couple of weeks ago. They were curious about them as they hadn’t seen this species before. They have more hours of observation in tidepools than any scientist I know. I was able to identify them as isopods, but that is as far as I could go on the spur of the moment. NOAA estimates that there are 10,000 species of isopods worldwide, about half of them found in every ocean and estuary in the world! The largest isopods are found in the abyss and can reach over 3 feet in length! Honestly, I would not want to meet one of those live and in person!

Some of the largest plankton are krill and feed the largest of animals, baleen whales.

My first foray into the scientific world was a job sexing Jassa falcata (a tiny amphipod) under a microscope. I had to count the eggs on the gravid (pregnant) females. This job convinced me I was not cut out for that kind of work. I just couldn’t envision myself spending my life over a dissecting scope with those tiny animals. My scientific career had to move in a different direction. I had a soft spot for the larger invertebrates, and I wanted to spend my life studying live specimens, not animals preserved in alcohol!

Ellen Goethel is a marine biologist and the owner of Explore the Ocean World at 367 Ocean Blvd. at Hampton Beach.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Plankton: The tiny creatures that sustain our oceans