Prisoners fight Tennessee's confusing life sentence laws — and notch some wins

With a set of outdated legal books, a typewriter, and centuries of prison time in the balance, Howard Atkins proved the state wrong.

He is trying to do it again.

Atkins, 40, is one of 1,828 people in Tennessee who are serving a life sentence in a state prison. Many of them say the prison department is incorrectly calculating their sentences, and a court has already sided with Atkins on one issue. The next issue could allow hundreds of them to reduce their sentences by more than two decades.

Until somewhat recently, a life sentence was presumed to mean a person spent their life in prison unless they were granted parole. But after a legal shake-up in recent years, Tennessee courts have decided that all those life sentences will actually end one day, regardless of if that person is granted parole — even if the state argues otherwise.

The issue Atkins and others are arguing now is just how soon they will end.

For some, it might have happened already.

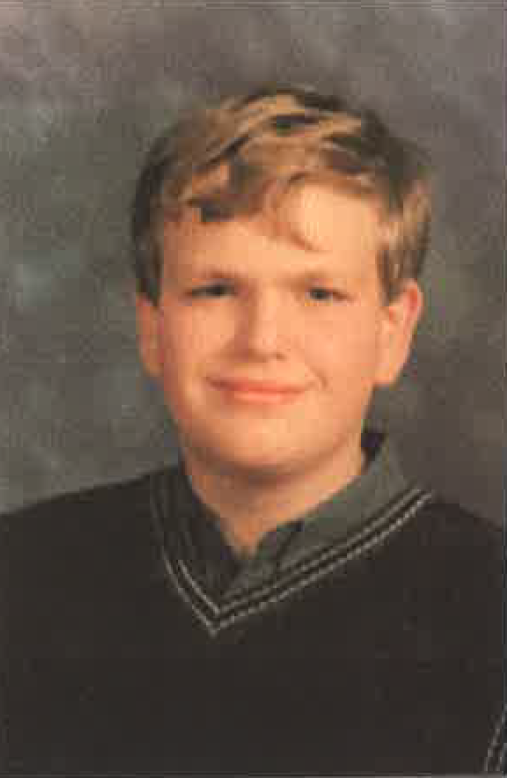

Sentenced to life at 17

Growing up, Atkins went by “Jeff.” He was raised by his father Tom Atkins, a Navy pilot who flew helicopters to help locate submarines before drawing airplane wiring diagrams for FedEx, and his mother Karen, who others say smothered him. Later talking to a psychologist, he called himself “his mother’s son and best friend.”

In a clemency petition, friends described him as caring and intelligent. He was a spelling bee winner and in the 99th percentile in reading and math, his petition shows. He loved to write stories, Atkins said.

After his parents divorced when he was 9, he stayed with his mother. A few years later, she found a new partner, Ray Conway. The relationship between his mother and stepfather was turbulent, emotionally abusive and at times physically abusive, he said. At one point, his mother exclaimed in front of her young son, “I wish he’d die and go to hell,” his aunt recalled in his petition.

“Jeff just dropped his head and stared at the floor,” she wrote.

Behind the headline: How we reported on Tennessee's life sentences

On April 6, 2000, Atkins’ father dropped him off at his mother's after a weekend visit. She was “hysterically sobbing,” Tom Atkins recalled.

Atkins, then 16, killed his stepfather with a baseball bat that night and called the police to confess. Atkins says that at the time, he feared Conway was killing his mother and he didn’t see a nonviolent way out of the situation besides abandoning her.

He regrets it “with every fiber of [his] being" and hates what his crime did to the Conway family.

Atkins was arrested and charged with first-degree murder. His mother paid for his lawyer with the life insurance money from her husband’s death.

He was tried as an adult, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001.

Atkins believed his sentence would last for the rest of his life but that he would have a shot at being granted parole — an early release from prison where he could live in the free world while still under state supervision — after 51 years.

“It’s strange to say, but … I never believed that I would actually end up having to do the full 51 years,” Atkins said. “I had a really immature conception of faith at that time, but that's what it was.”

The effects of a harsher law, decades later

The law that Atkins was sentenced under was part of a sentencing package Tennessee lawmakers passed in 1995. Under a 1994 federal law sponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, states received federal funding if they instituted harsher criminal penalties.

The new life sentencing statute was ambiguous. It said that a person sentenced to life "shall serve one hundred percent (100%) of the sentence imposed by the court less sentence credits earned and retained" for a maximum of 15% off their sentence.

However, it was written on top of the previous law from 1989, which had allowed those serving a life sentence to become eligible for parole at 60% of 60 years, but as early as 25 years. If all this sounds confusing, that's because it is.

Longtime Nashville defense attorney David Raybin, who was part of the Sentencing Commission that crafted the 1989 law, remembers speaking against the 1995 law, which he called “ill-advised” and “poorly written.” Speaking about the law in an interview, Raybin said, "I don't know what it means."

He said he warned lawmakers then that they wouldn't “see the effects of this for years.”

“But here we are,” Raybin said. “And now we see it.”

How things got where they are

The current state of life sentences in Tennessee is so complex and confusing that it has led scores of prisoners to file challenges to their sentences in court. At least 107 people serving life sentences have made some sort of challenge to their sentence in federal court from July 2023 through early June 2024.

Part of what threw the system into disarray is a Tennessee Supreme Court decision from December 2018 in which the court wrote that “life” sentences were determinate sentences lasting 60 years.

But even a few years later, Atkins noticed that the Tennessee Department of Correction had not updated his sentence calculation to show an “expiration date” in accordance with that 2018 decision. He wrote numerous letters to prison officials, who told him repeatedly that his sentence did not expire.

So, unable to leave his cell due to staffing shortages at Northeast Correctional Complex, he handwrote the first draft of his lawsuit. Once he could make it to the prison’s law library, he sat down at a typewriter and asked the Davidson County Chancery Court to order TDOC to change his 51-year parole eligibility date to a sentence expiration date.

David Esquivel, an attorney at Nashville law firm Bass, Berry & Sims, read the lawsuit, filed in March 2022, and it blew him away.

“Honestly, if you had taken his name off of it, I would have thought a lawyer did it,” Esquivel said. He now represents Atkins pro bono.

In September 2022, the state agreed Atkins was right and gave his sentence an expiration date.

Now, others say the department must do the same for them.

It's unclear if the state has conceded all life sentences have an expiration date. The attorney general’s office argued as recently as February that they do not, but courts have shot it down. In April, Davidson County Chancellor Patricia Head Moskal ruled in favor of another prisoner who sued TDOC without a lawyer, writing that a “life sentence is 60 years, regardless" of when the offense was committed.

The attorney general's office and TDOC declined to comment on the record for this story.

How things have changed: What should a life sentence mean in Tennessee? More Republicans say an earlier shot at parole

How short could a life sentence be?

Now, courts are siding with incarcerated people that life sentences in Tennessee end between 51 and 60 years. Could they be even shorter?

Atkins and Esquivel argue that for two groups of lifers, they can. Atkins says that juveniles and people sentenced before 1995 may be able to reduce their actual sentence by more than a third — if their argument succeeds.

Atkins argues that now that life sentences appear to be 60 years, they should be eligible to earn time off their sentence through credits called “good time.” TDOC calculates these credits using a complex formula, but Esquivel thinks it comes out to about 38 years in prison if a prisoner earns the maximum amount.

They believe this could only apply to juveniles and pre-1995 offenders because they are both serving time under the same law — after a 2022 court ruling outlawed applying the 1995 law for juveniles, they simply started serving time under the law as it was written in 1989.

Around 460 people are serving life sentences from before 1995 or were sentenced as juveniles, according to data from TDOC.

Why does this matter?

Raybin, the defense attorney, said this development is significant because of low parole rates in Tennessee.

Remember that the 1989 law, which also applies to people sentenced to life as juveniles, allows for parole as early as 25 years. But Raybin, who has handled many parole cases, said the Board of Parole (BOP) usually denies parole for people serving a life sentence until at least 30 years, and often longer. Among all incarcerated people who went up for parole in the last fiscal year, the board granted parole to only 25.9% of them, data from the BOP shows. The rate for initial parole hearings is even lower — in 2019, the most recent year for which data was readily available through a state report, it was 10%.

Atkins said he knows more than a dozen people in Northeast Correctional Complex who have served more than 40 years on a life sentence because they were never granted parole.

If the court rules that good time credits do apply, they should be able to get out of prison, Atkins argues.

“There's some of them that ask me a couple times a week, ‘Have you heard anything yet? Have you heard anything yet?’” Atkins said. “And I'm like, ‘No, not yet. It's coming.’”

'Disregard for humanity'

This low parole rate is one reason the state’s prison population has ballooned despite a falling crime rate since 1997. Another reason is that sentence lengths have also increased “dramatically,” with the average incarcerated person spending 23% longer behind bars in 2018 than in 2009, Gov. Bill Lee’s Criminal Justice Investment Task Force found in 2020.

This has created a feeling of hopelessness for some. Kenneth Thomas, serving a life sentence at Nashville’s Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, has petitioned a court to allow him to die by euthanasia.

“If I'm going to die in prison, I'm not going to sit here and suffer for 30 years,” Thomas said in an interview.

Dawn Deaner, a criminal justice advocate and founder of the Choosing Justice Initiative, pointed to data in the 2020 report that showed longer sentences do not improve public safety.

“It’s just tragic, the waste of potential and disregard for humanity,” she said.

It also comes at a cost to taxpayers. In the 2024 fiscal year, the estimated cost to incarcerate one person in a TDOC facility is $106 per day, according to the Sycamore Institute.

For many, challenging how TDOC calculates their sentences is one of the few potential forms of legal relief they have, Deaner said. But that relief is not available to everyone.

“I think the biggest place of sadness for me is people who've received life sentences over the last 30 years who were not juveniles," Deaner said. Lawmakers have introduced bills to give prisoners an earlier shot at parole, but they have not passed.

How sentencing changes impact victims

Valerie Craig at Tennessee Voices for Victims said that many family members of murder victims felt that the increase to 51 years for a life sentence “felt more like justice.” Shortening these sentences can make victims feel ignored, Craig said.

Still, she said she thinks the justice system is broken. Most people in prison are not rehabilitated, and the Board of Parole rarely recognizes those who are, she said. To her, the problem shouldn’t be fixed through shortening life sentences, but by making prisons more rehabilitative and improving the parole and clemency process.

“There's a lot of similarities between people who are incarcerated and victims in terms of how they view the system,” Craig said. “They all feel like it's unjust. They all feel like it's unfair. They all feel like it doesn't communicate well. And I would agree with that.”

'He will always have a place to go'

At the start of his incarceration, Atkins was depressed. He gained more than 100 pounds, up to the highest value on the prison scale, and was put on medication for his mental health. But in 2012, he read three words from a religious magazine his dad sends him called “Guideposts,” and he said it inspired him to turn things around: “Tomorrow is now.”

Now, he holds a job gardening at the prison, tries to exercise regularly and takes several classes. In addition, he does legal research nearly every day and has a clear disciplinary record.

He goes up for parole next year. He knows he might be denied, especially after his clemency petition wasn’t granted in 2023, which he said changed his view of the system. He had 37 different certificates, awards or designations earned in prison, and recommendations from dozens of correctional officers.

It is a relief knowing that even if the board denies his parole for years, his sentence will still end, he said.

And when it does, he will have a home.

Atkins’ mother, Karen Conway, eventually found a good relationship, Atkins said. She married a man named Larry Hughes, a cross-country truck driver, in 2007.

When she died of lung disease in 2015, Hughes was by her side “because I couldn’t be,” Atkins said.

“I have always told Howard that if and when he is released, he would be able to come live with me,” Hughes wrote in Atkins' clemency petition. “I still hope that he does. He will always have a place to go.”

And he'll get him something that he's been missing over the past 23 years in prison: good fish.

"I'll buy him the best plate of fish he's ever had," Hughes said.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Tennessee prison, sentencing laws leave incarcerated folks in limbo