How a pro-Palestinian artwork placed in a Jewish enclave shook up this Miami arts nonprofit

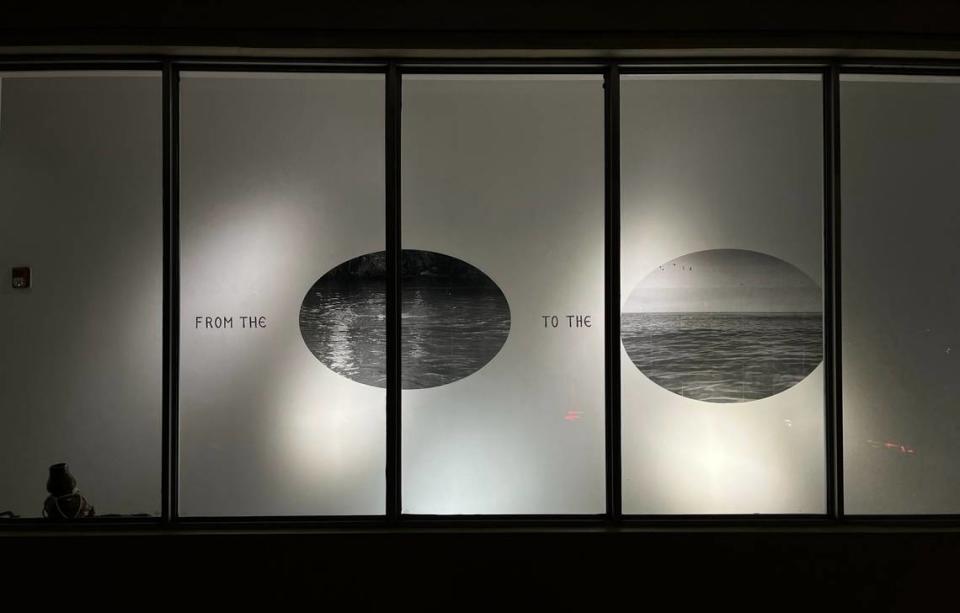

In the window of a Walgreens in Miami Beach, a community with a high concentration of Jewish residents and a reputation as an international hub for arts and culture, an art installation referenced a highly controversial six-word phrase: From the river to the sea.

For some, the phrase is a rallying cry for Palestinian equal rights, autonomy and freedom often chanted at protests around the world calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. For others, that same phrase is hate speech that calls for genocide against Jews and the destruction of Israel.

The artwork was rather subtle. Instead of the word “river,” there was an image the artist took of the Jordan River. Instead of the word “sea,” there was a photo of the Atlantic Ocean taken in Miami Beach.

The placement of this work in a public space in the midst of Miami Beach’s Jewish community, a local art organization’s decision to remove it and the subsequent backlash from artists accusing the group of censorship has splintered Miami’s tight knit arts community along the same fault lines seen throughout the world.

Those critical of the artwork questioned how the group, Oolite Arts, allowed it to go up in the first place. Those critical of the artwork’s removal questioned why Oolite didn’t consult with the artist before deciding whether to take it down, raising concerns about political censorship.

Interviews with many of the parties involved made several things clear. Vũ Hoàng Khánh Nguyên, the artist who goes by Vũ, added the artwork to the exhibition to show support for the Palestinian people and didn’t tell Oolite about this specific work ahead of time. Oolite staff did not speak to the artist about it after it was installed. And about five weeks went by until someone called Oolite to complain about the work, bringing it to the board’s attention for the first time.

Weeks after the work was removed, the local arts community is still reeling from the controversy, with some artists calling for a boycott of Oolite and the resignation of board chair, Marie Elena Angulo. Many demanded a meeting between the artistic community and the board. Meanwhile, others who support Oolite’s decision to remove the artwork feel silenced.

There is one thing everyone can agree on, though. Miami’s arts community has never seen something quite like this.

‘That was not the intention at all’

Oolite Arts boasts a sizeable reputation in Miami’s arts scene. Founded in 1984 as ArtCenter/ South Florida, the organization provides local artists with free studio space, grants, professional connections and exhibition opportunities. The nonprofit changed its name to Oolite Arts, referencing the bedrock of Miami, in 2019.

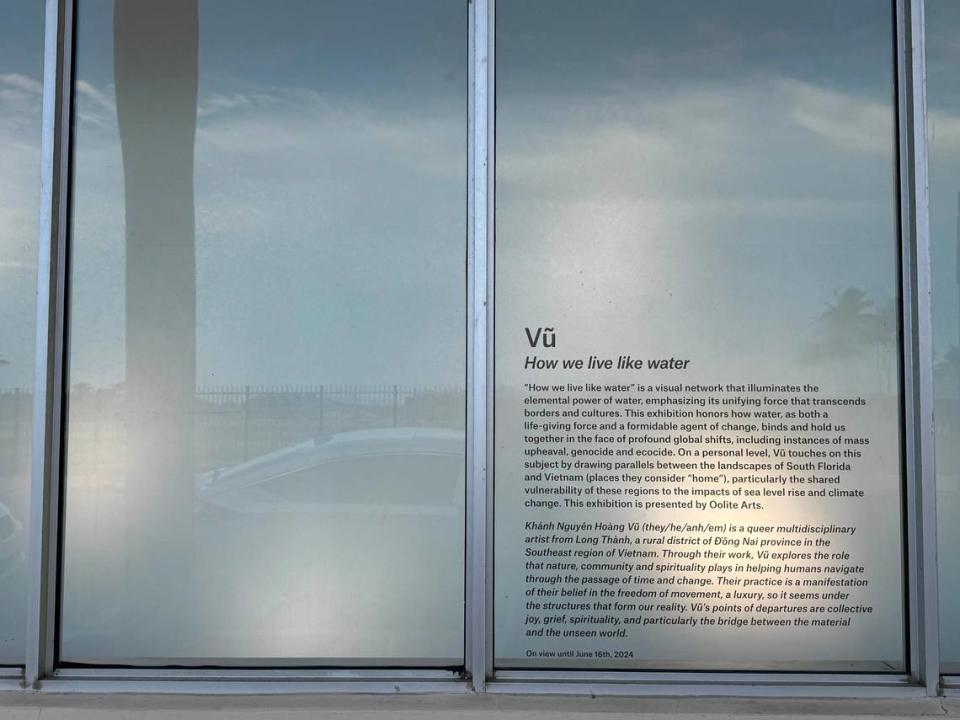

Oolite has had an agreement with Walgreens since 1999 to display art publicly in the windows of two Miami Beach locations. Oolite staff typically reaches out to artists who have worked with the nonprofit in some capacity before. That is how Vũ, who participated in Oolite’s travel residency program in 2021, got a call from Oolite curator Laura Guerrero about working on an exhibition at the Walgreens on 67th street and Collins Avenue.

Vũ, a visual artist and tattoo artist, was born in 1997 in a rural part of Vietnam and immigrated to the United States with their family as a child, eventually settling in Florida. Vũ grew up with a talent for drawing and earned a full college scholarship to New World School of the Arts in Miami. The artist graduated in 2020.

In their proposal for the Walgreens exhibition, Vũ outlined a general idea that would include pottery, fishing nets and artworks that alluded to bodies of water. “With this project I’d like to play with combining 2D mediums such as painting and drawing with found/hand made object assemblages. I thought this would be a great way to play with and showcase the breadth within my practice,” the proposal said. The window display, entitled “How we live like water,” focused on water as the “unifying force that transcends borders and cultures,” according to the exhibition description on Oolite’s website. The artist didn’t mention the phrase “from the river to the sea” or Palestine in the proposal.

It was approved by the board, Vũ said, and was set to be displayed from March 27 to June 16.

Vũ got the keys to the window space from the curator on March 20 and installed all of the works in the exhibition with the help of some friends. One night that week, Vũ came up with the idea to create the “from the river to the sea” artwork.

Gaza was front of mind for the artist. Raised in a family displaced by war, Vũ empathized with the plight of the Palestinian people. Vũ said they wanted to use their platform to make a statement.

“I knew it could be found controversial, yes, even offend, but I didn’t think they would take it as a literal call for violence towards them,” Vũ said. “I’m trying to call for peace, for no violence for anybody. Why would I wish more violence upon you? That was not the intention at all.”

Vũ said that no one from Oolite expressed any concern about the artwork or talked to them about it before May 3.

That was the day Angulo said she received a call from a man who found her name on the Oolite website. He told her that he was asked by some members of the community to question “why that piece was on the Walgreens window in the middle of a Jewish community and to ask me what Oolite was planning to do about it.”

Angulo said she told him she was not aware of the piece and that she would investigate. She told the Herald that she quickly consulted with the board’s executive committee, who are charged with making fast high level decisions.

After a flurry of text messages to Oolite’s acting interim directors Esther Park and Munisha Underhill, the artwork was taken down within a few hours.

To Angulo’s knowledge, this was the only complaint Oolite had received about Vũ’s artwork.

The ‘centerpiece’

Angulo said she didn’t see how the “from the river to the sea” artwork was a last minute decision by the artist.

“It was the largest piece of the whole show. It was actually the centerpiece of the show,” Angulo said. “It was not added to fill at all. It was added to be the main attraction of the show.”

Angulo said that artists who work on a Walgreens exhibition sign an agreement with a clause “that states that any [art] piece added should be approved.” But Vũ’s characterization of the process was that it wasn’t very strict and that no one from Oolite explicitly told them that the artworks could not be controversial or political.

Vũ said they were not asked to provide an itemized list or description of each artwork that would be in the show and that Oolite was aware that there would be new artworks that had never been seen before.

“I thought I had artistic freedom to do what I want, but I guess not,” Vũ said.

Loni Johnson, a Miami-based artist and the 2021 recipient of Oolite’s Social Justice Award, also had her work displayed in a Walgreens window in the past and described a similar experience. Nobody knew what the final product would be until it was already up, Johnson said.

Vũ said they would’ve appreciated Oolite having a conversation with them about the complaint instead of rushing to take the work down.

“I just felt very disrespected. Where was the integrity in that on their end?” Vũ said. “Why was I not allowed to consent to the removal of the work?”

But Angulo said that even if she had met with Vũ prior to removing the artwork, the outcome would’ve been the same.

“We acknowledge that the process could have been handled better. We are not really looking at this as censorship,” Angulo said. “We would have taken the same action even if we had taken more time to talk to the artist because we would have done the same in any other context where there was an offensive statement to the members of the community that is viewed by a large number of people in that community as offensive.”

The decision to remove the work boiled down to the phrase’s controversial nature and the exhibition’s location in a large Jewish community, Angulo said. She drew this comparison: If she had gotten a call from a Black resident about a Confederate flag in a Walgreens window, she said, she would’ve made the same decision.

‘The good thing out of this bad thing’

How did this happen if it technically violates Oolite’s own policies? Angulo said Oolite’s staff has been juggling too much.

The people involved in the day to day running of the organization at the time it was installed were Underhill and Park, who are respectively the vice president of development and vice president of programming. Neither responded to a request for interviews. Guerrero, the curator, also didn’t respond for comments. The Miami Herald could not verify if any Oolite employees saw Vũ’s final work installed.

In the last six years, Oolite has awarded $3 million to artists through its annual Ellie’s Awards, funded feature films through its Cinematic Arts Residency program and started a $12,000-a-year housing stipend initiative for resident artists. After the $88 million sale of one of its Lincoln Road buildings, the group is currently overseeing the construction of its $30 million new facility in Little River.

Angulo said the organization’s staff of less than 10 people has been affected by leadership changes. After the previous CEO and president Dennis Scholl stepped down from Oolite after six years, Tania Castroverde Moskalenko was hired as interim CEO, but she left the organization in February to accept another job. Underhill and Park then took on the roles of co-interim directors in addition to their other duties, Angulo said.

After the Walgreens situation, the group removed Underhill and Park as co-interim directors to “focus on their respective roles” and hired Maggy Cuesta, the former dean of visual arts at New World School of the Arts, as interim director, Angulo said. Cuesta began on May 13, ten days after Vũ’s art was removed.

In a June 4 public statement shared on Instagram, Oolite’s board of trustees stood by its decision and said it is “committed to evaluating our decision-making in this matter and to put in place policies so that artists we work with have clear guidelines and expectations.”

”The Oolite Arts Board of Trustees deeply regrets that the removal of Vũ Hoàng Khánh Nguyên’s artwork has offended some in our community, and that its contents offended others in our community. We believe strongly in the right to artistic expression, but the particular phrase highlighted in this piece is perceived by many as a literal call for violence against them,” the statement said.

Oolite hired a consultant to conduct a review on the incident.

“The good thing out of this bad thing is that we have had time to review our internal processes and know where to make improvements,” Angulo said.

‘We’re here to tell the times’

The fallout from the removal of Vũ’s work in Miami’s arts community was swift.

Days after the work was removed, Vũ posted an online statement about the incident, along with an open letter written by a group of artists that accused the organization of censorship and listed several demands. The open letter now has over 700 signatures. An art exhibition at Oolite’s Lincoln Road location featuring its resident artists was postponed indefinitely in support of Vũ.

“It’s been totally overwhelming to be honest, but I’m grateful for the community backing me up,” Vũ told the Herald. “I’m glad it’s grown into something kind of beyond me at this point and artists are realizing how powerful we are together.”

This wasn’t the first time a Miami arts institution removed an artwork related to Palestinian people, which has further sparked concerns among artists about censorship. Arts publication Hyperallergic reported that the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami quietly removed a portrait of the Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said from an exhibition of Charles Gaines’ work and later re-installed the piece.

“[Artists] have to speak out on this as a collective,” Johnson said. “Just because it wasn’t you now, it could be you in the future.”

Harmony Honig, a Jewish Miami-based performance artist who did not find Vũ’s artwork to be hate speech, signed the open letter criticizing Oolite’s decision as censorship.

“It’s just really shameful that what’s supposed to be a public arts institution would try to shame artists for speaking out against a genocide that’s happening in Palestine,” Honig said. “It’s one thing to not publicly condemn it, and it’s another to censor artists who want to speak about it.”

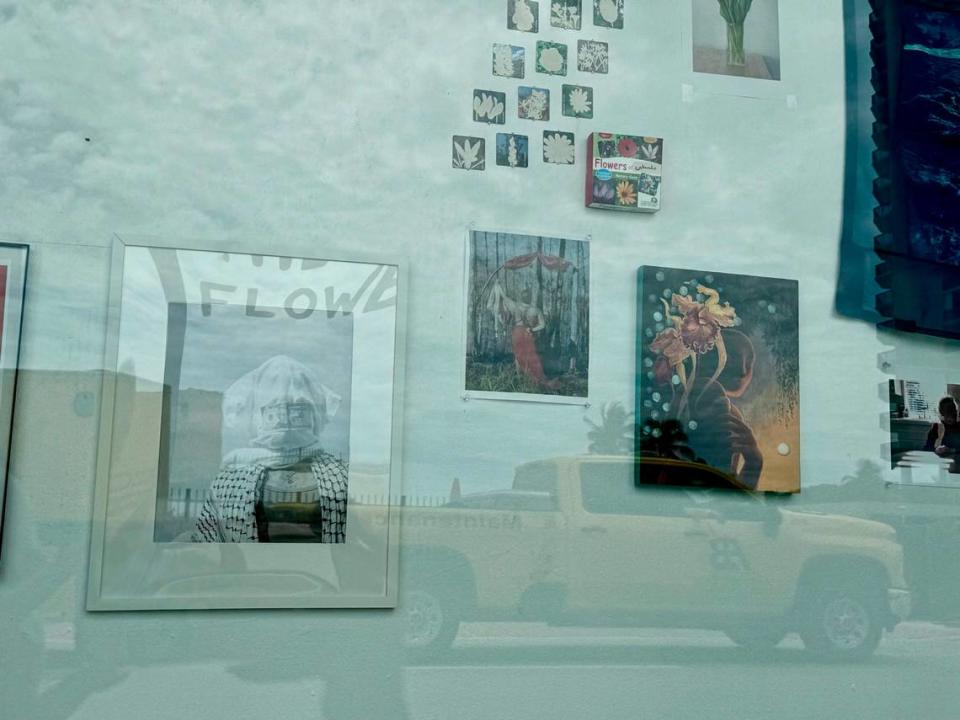

In June, several South Florida artists protested Oolite’s decision by adding pro-Palestinian artworks to the blank space at the Walgreens, including images of watermelons, keffiyehs and the phrase “Killing the flowers will not delay spring.” The works were visible for several days until all the Walgreens windows were covered.

Elias Rischmawi, a Palestinian Miami-based artist, participated in the action. Arts organizations tend to present themselves as progressive on most social issues, Rischmawi said, but “not for Palestine.”

“An organization like that should never censor any artists because they understand what an artist’s role is in society,” Rischmawi said. “We’re here to tell the times, and that’s what Vũ was doing.”

Others in the arts community didn’t see it as censorship. For Ariel Baron-Robbins, a Jewish Miami-based artist who had a studio at Oolite from 2014 to 2016, the phrase is inseparable from its association with the militant group Hamas. “It’s such an extreme sentence that something did need to happen immediately,” she said.

“I felt sad because the people that were the loudest about it and saying this was this horrible thing Oolite did, I felt like I would love to have a conversation with them and carefully explain what it was that made that statement so bad,” she said. “But then I also felt like my voice would not be heard.”

Angulo said she has received several messages from people within the arts community who support Oolite’s decision. Among those who agreed with Oolite is David Schaecter, a 94-year-old Holocaust survivor and former partner of Miami arts storage facility Museo Vault.

“Six million Jewish people, including 1.5 million children, and 105 members of my family, were murdered because slogans like this one were ignored and excused, at the same time they fostered unprecedented genocidal hatred. I know – I was there,” Schaecter wrote in a statement.

Some in the community find themselves somewhere in between, like one former Oolite resident artist who asked not to be named. The artist didn’t agree with how Oolite handled the situation, but didn’t find it necessary for Angulo to step down.

“This is a very delicate matter, and it should be treated with sensitivity and care on both sides,” the artist said. “We are dealing with people’s lives and reputations, and we have to all remember no organization is perfect. There is always work to be done.”

The conversation continues

Just two days after Oolite’s public statement was posted on Instagram, several Miami artists shared posts online calling for a boycott. Johnson was among the first to do so.

“These organizations and these institutions feel like they can treat artists any type of way and don’t realize the pull artists can have,” Johnson said. “They are indebted to us, not the other way around.”

The boycott asks artists to not participate in Oolite exhibitions, lectures, film screenings or open studio events. It does not ask artists to leave the Oolite studios they’re already in or return or refuse grant money.

“That would be antithetical to what we’re trying to do here,” said artist and boycott organizer Misael Soto. “If an artist is going to take advantage of the space that was afforded to them according to merit, they flat out deserve that and should be taking advantage of that wholeheartedly without the need to give back anything to Oolite. It’s not a trade.”

Soto said organizers don’t deny the positive impact Oolite has had on artists’ careers, but they do believe Oolite’s board is in need of structural change, like majority artist representation. Organizers will continue the boycott until there is a town hall discussion with Oolite, its resident artists and the wider artistic community.

Angulo found the boycott to be preposterous.

“I think it’s fascinating that they are willing to boycott certain things but are very happy to keep getting their free studios and their $1,200 housing stipend that they get each month,” Angulo said. “And that they are not boycotting our money or resources even though apparently our money is dirty money.”

But there is hope for continued dialogue. After a meeting between Vũ and Angulo in late June, the Oolite board will meet with Oolite resident artists to discuss the matter on Aug. 7.

“It’s good to have these kinds of discussions in person,” Vũ said. “There’s so much to be communicated that can’t be done through the internet.”

This story was produced with financial support from individuals and Berkowitz Contemporary Arts in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.