Rare 'polar rain' aurora seen from Earth for the first time

A remarkably smooth and puzzling Christmas Day aurora observed over the Arctic in 2022 was the result of a 'rainstorm' of electrons direct from the sun, says Japanese and US-based researchers.

It is the first time that a rare aurora of this kind has been seen from the ground, and it came at a time when the gusts of the solar wind had almost completely dropped off, leaving a region of calm around the Earth.

Normally the aurora displays, like the ones seen around the world in May, move and pulsate, with clearly discernible shapes in the sky. These auroral displays are powered by electrons from the solar wind — a stream of charged particles that flow from the sun — that become trapped in an extension of Earth's magnetic field called the magnetotail. When space weather becomes extreme, such as when a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a large ejection of plasma and magnetic field from the sun— is released, the magnetotail can be pinched off (don't worry, it regrows). The electrons trapped there flow down Earth's magnetic field lines to the poles. As they do so, they encounter molecules in Earth's atmosphere, colliding with them and prompting them to glow in the colors of the aurora (blue for nitrogen emission, green or red for oxygen depending on its altitude).

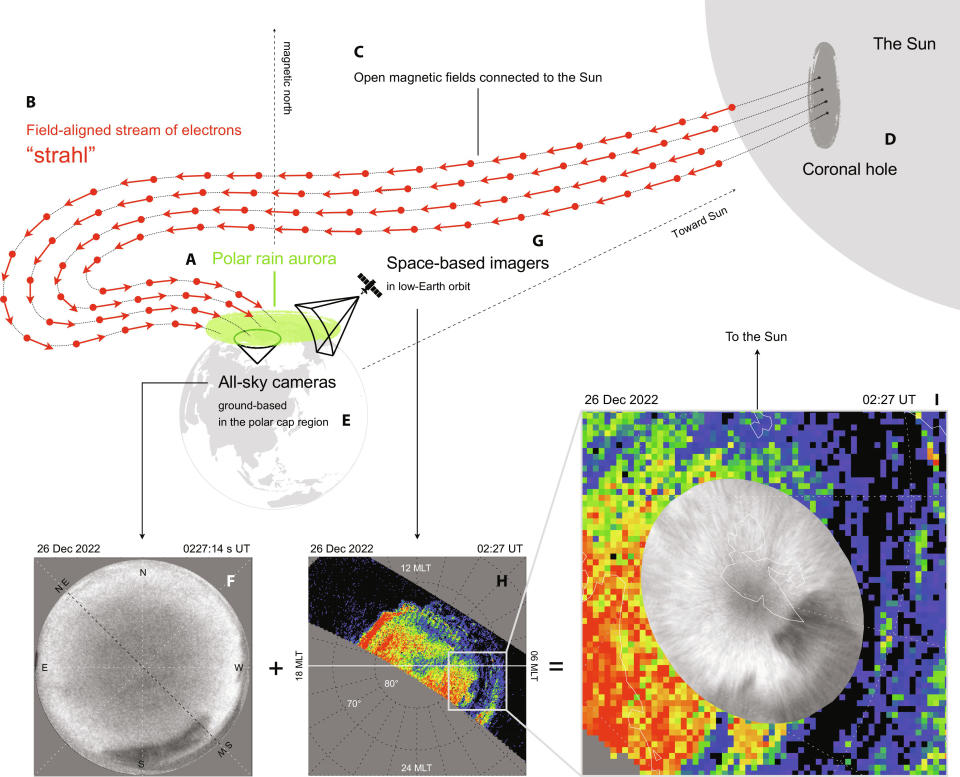

However, the smooth aurora of 25–26 December 2022 was very different. Imaged by an All-Sky Electron Multiplying Charge-Coupled Device (EMCCD) camera in Longyearbyen in Norway, the aurora was a faint, featureless glow that spanned 2,485 miles (4,000 kilometers) in extent. It had no structure, no pulsing or varying brightness. No type of aurora like it had ever been seen from Earth before.

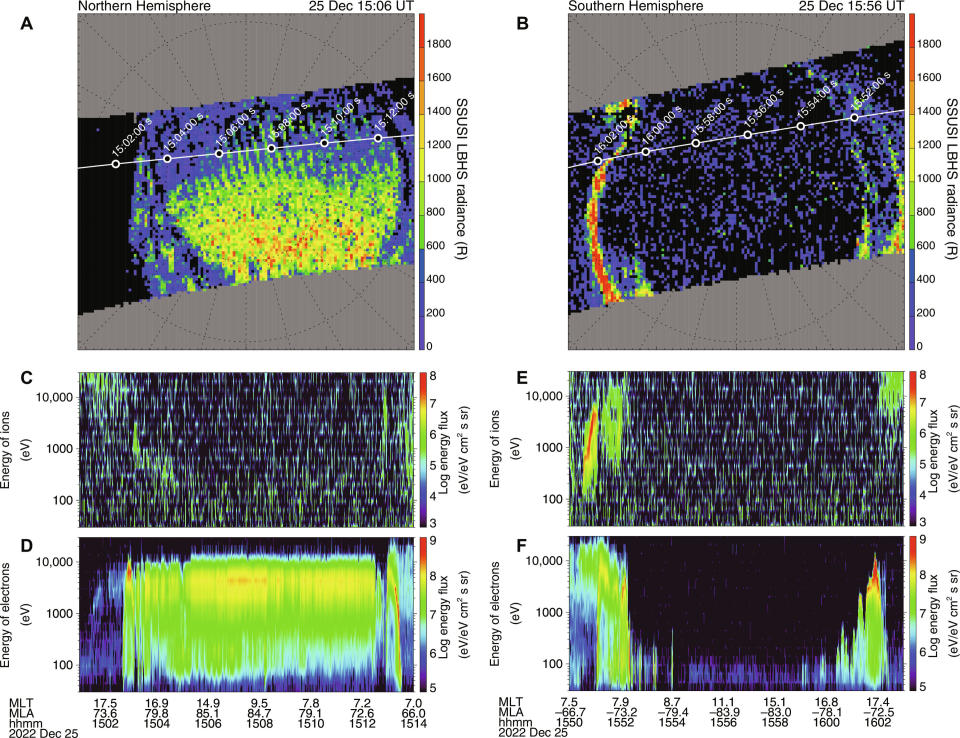

To solve the mystery a team led by Keisuke Hosokawa, of the Center for Space Science and Radio Engineering at the University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo, compared this bland aurora with what the Special Sensor Ultraviolet Scanning Imager (SSUSI) on the polar-orbiting satellites of the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) saw. The DMSP is operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the US Space Force on behalf of the US Department of Defense.

The satellites saw the aurora from above, finding that it had all the hallmarks of a rare type of aurora called polar rain aurora, which had only ever been seen from space before.

The regular solar wind travels about 250 miles (400 km) per second. However, the sun's hot corona is full of holes, particularly at higher solar latitudes from which an exceptionally 'fast' solar wind moving up to 500 miles (800 km) per second streams out. Sometimes these coronal holes can appear at lower latitudes, and that is what happened over Christmas of 2022 while coinciding with a cessation of the regular solar wind.

At the location of coronal holes, the sun's magnetic field lines are open — they don't loop back onto the sun's surface, the photosphere. As the open magnetic field lines extend out into space the coronal hole forms the base of a magnetic funnel out of which stream high-energy electrons.

In the case of the polar rain aurora, these electrons traveled across space, and the open magnetic field lines connected with Earth's magnetic field above the north pole, allowing the electrons to rain directly onto the poles rather than getting trapped inside the magnetotail.

Normally we don't notice this happening, because the regular polar wind particles scatter the fast-wind electrons emanating from the coronal hole. On this occasion, however, the pressure of the solar wind had decreased to the extent it was negligible, and the fast-wind electrons could reach Earth unhindered.

Related stories:

— How a giant sunspot unleashed solar storms that spawned global auroras that just dazzled us all

— Aurora myths, legends and misconceptions

Furthermore, the diameter of this magnetic funnel opening is about 4,600 miles (7,500 km) when projected at Earth's distance from the sun. That's why the aurora seemed so smooth; the open magnetic flux tubes emanating from the sun covered a wider area than Earth's north polar cap. Because the electrons were high energy, the auroral emission was purely green rather than red because it takes more energy to ionize oxygen deeper in the atmosphere.

The clinching evidence was that the DMSP satellites only saw the polar rain aurora over Earth's north magnetic pole, which is tilted towards the sun during Northern Hemisphere winter.

"When the solar wind disappeared, an intense flux of electrons with an energy of >1keV was observed by the DMSP, which made the polar rain aurora visible even from the ground as bright greenish emissions," said Hosokawa's team in their published research paper.

The polar rain itself has previously been studied in-depth by particle detectors on satellites in orbit, but such studies are few and far between. These smooth auroras are not normally visible to the naked eye on the ground. As such, nobody knew what the smooth, featureless aurora that turned the sky green over Christmas of 2022 was, until now. The full explanation can be found in the 21st June edition of the journal Science Advances.