Renewable energy alone can’t save Ukraine’s faltering grid

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Scoop

A top US energy company said it will prioritize Ukraine for the delivery of vital, backlogged hardware as the country fights to keep the lights on after losing half of its power capacity due to Russian attacks.

At a Ukraine recovery conference in Berlin on Tuesday GE Vernova signed an agreement with Ukrainian Energy Minister German Galushchenko, committing to sell the country critical electricity hardware including small mobile gas turbines, microgrids, renewables, and utility-scale batteries.

“We have years and years of backlogs for a lot of this equipment,” Roger Martella, the company’s chief sustainability officer, told Semafor. “Instead of just answering the phones in the order in which they ring, we’re having very serious conversations at the highest levels of the company about how we can move equipment around and reallocate it so that we’re putting Ukraine first and foremost.”

GE Vernova’s deal with Kyiv represents one of the biggest forays by a foreign energy company into Ukraine since Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion. Blackouts are increasingly common in Kyiv and other cities, and promise only to worsen once temperatures rise in the summer, requiring increased use of air conditioning, before they begin to plummet again and force a surge in demand for heating.

Reconstruction work on the damaged grid is being held back by a combination of factors including labor and equipment shortages; insufficient defensive rockets to protect infrastructure from repeat attacks; electricity market policies that private project developers say deter investment; and cold feet by many foreign energy companies about operating in a war zone.

For GE Vernova, those challenges aren’t enough to deter it from the opportunity to pilot its vision of the clean energy system in Ukraine.

“This will probably be one of the biggest infrastructure projects of our generation, and really set the tone for the rest of the world about what a sustainable energy ecosystem looks like,” Martella said.

Tim’s view

Before Ukraine can reach a clean energy future, it’s going to need a lot more fossil fuels, and moving past them will require some big policy changes that the government has so far been unwilling to make.

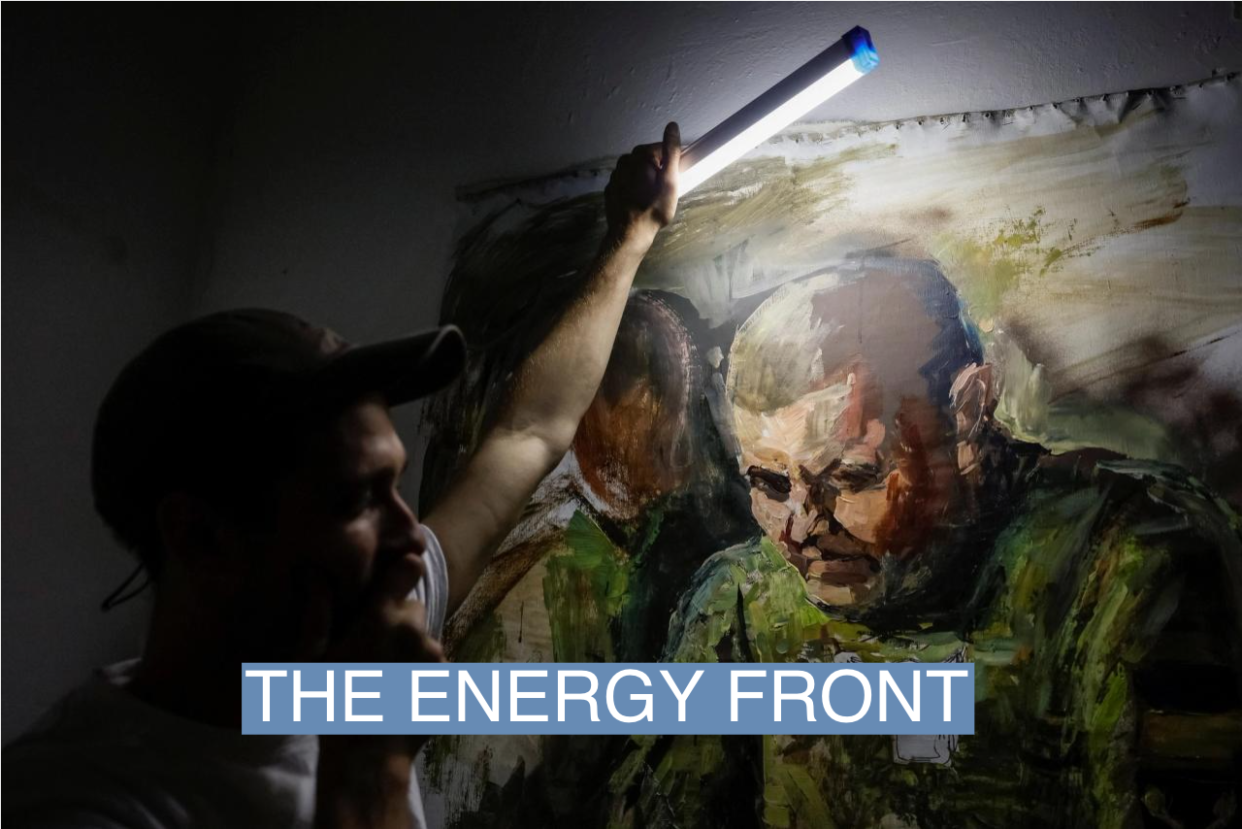

Russia’s strikes on the energy network are designed to wear down Ukrainian morale. The situation in Kyiv was particularly strained over the last week, as some of the country’s nuclear power plants, which are the only remaining source of steady baseload power, were taken offline for routine maintenance. Even as those come back online, the din of diesel generators is now a fixture of the city’s soundscape, and home batteries that can at least keep phones charged and some lights on are growing harder to find. Beyond the daily annoyance of blackouts, a stable energy supply is critical for Ukraine’s military readiness and economic recovery.

The country’s pre-war power generating capacity, about 18 gigawatts, is now down to half that number because of Russian strikes on gas- and coal-fired power plants, substations, and other grid infrastructure. Analysts expect no more than 3 gigawatts to be recovered this year; if consumption rises during the summer, blackouts of 20 hours or more could become routine, a top grid official warned last week. Russia is also now increasingly targeting infrastructure that had previously gone unharmed, including solar farms and natural gas storage facilities and pipelines. Officials fear that transformers near nuclear plants may be next, with the risk of catastrophic meltdowns if missiles strike the plants themselves.

“These losses are really unprecedented in any energy system,” Galushchenko told the Berlin conference. Ukrainian engineers have been deployed to comb Europe for disused hardware, he said, and the country is desperate to attract more aid and investment from abroad. “All the [energy] equipment we can get becomes our weapon to win the war.”

Ukraine’s energy recovery has two phases, the immediate and the long-term. Long-term, the country has incredible renewable energy potential; a report this week from the consulting firm Berlin Economics projected that, in a scenario with no war, the country is capable of adding 14 gigawatts of solar by 2030, nearly equal to Ukraine’s total generating capacity today.

Rebuilding destroyed Soviet-era fossil power plants makes little sense and in any case would probably be impossible to finance as banks raise their ESG standards, said Andrian Prokip, director of energy at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, a think tank. Excess clean power could also become a lucrative export commodity to Europe.

But in the immediate term, there’s little chance that renewables can be built fast enough, with the necessary storage and grid transmission capabilities, to make them effective. “We shouldn’t care too much about pollution and everything, because the priority is just to have power,” Prokip said.Speaking in Berlin, top German climate official Robert Habeck said the fastest stop-gap solution will be a fleet of hundreds or thousands of small gas turbines that can be easily transported and set up to supply individual facilities like hospitals or small clusters of homes and businesses. Martella agreed: “For this winter, there’s a prioritization and focus on conventional power.”

Whatever the source, Ukraine’s energy recovery and transition are held back by its byzantine, government-controlled wholesale market and project finance rules. Electricity prices are kept artificially low, which the government sees as a crucial lifeline for embattled households but which deters investment, Igor Tynnyi, a developer of solar, hydro, storage, and biogas projects and co-founder of the Ukrainian Association of Renewable Energy trade group, said. The state-controlled grid operator is chronically late with payments and currently owes at least $500 million to renewable energy developers, according to the Berlin Economics report. Banks require steep collateral commitments and third-party guarantees on renewables projects that make them nearly impossible to finance, Tynnyi said. “If you want private businesses to quickly develop those hundreds and thousands of small stations to replace what has been destroyed, you need to lose all these requirements,” he said.

Officials in President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s administration occasionally talk about liberalizing the energy sector and building a new decentralized system, Prokip said, but remain reluctant to cede control during wartime. A spokesperson for the Energy Ministry didn’t return a request for comment by deadline.

“Last year they built something like 500 megawatts,” Prokip said. “That’s not success.”

Room for Disagreement

The bureaucracy that frustrates Tynnyi is comforting to Martella, who said that the level of coordination between the US and Ukrainian governments with private energy companies “has been the best example of public-private partnership in the 30 years of my career.” In Ukraine’s chaotic situation, companies like GE Vernova are best suited to deliver what the government asks for, rather than initiate projects on their own, Martella said.

One other concern with the gas turbine strategy is that Ukraine’s gas supply is also tenuous. Last year the country survived on its own supply but increasing demand for small turbines and the destruction of gas storage facilities may require it to start importing gas this winter, Prokip said — something the country can scarcely afford.

The View From Baku

Meanwhile, European officials are scrambling to decide how to address a December deadline by which Russian gas that continues to flow to Europe through pipelines in Ukraine will likely be cut off. The pipeline flows are a curious artifact of the pre-war period, a case in which Ukraine and Russia effectively collaborate to serve Europe’s gas needs, and both profit well from doing so. But Europe and Ukraine are desperate to cut off Russia’s fossil fuel revenue. Instead, Bloomberg reported, officials may work out a deal to replace Russia’s gas in the pipelines with imports from Azerbaijan.

Notable

Russia is also scrambling to find new customers for its sanctioned oil exports, and getting help in building out its “shadow fleet” of oil tankers from an unusual ally: Gabon.