Research shows heat exposure disproportionately affects Black Richmonders

A first of its kind study looked at disparities in temperature in communities across Virginia. (Getty Images)

RICHMOND – Michael, a resident of Richmond’s Southside who declined to share his last name, sat on Forest Hill Avenue waiting for a bus Tuesday just before 2 p.m., when a car thermometer recorded the temperature at 94 degrees.

Michael wasn’t waiting under a bus shelter as he headed home from a doctor’s appointment. Rather, he was sitting underneath a narrow sign that provided a sliver of shade as the sun beamed down.

“There’s very little shade right here,” said Michael, who added additional cooling centers would help alleviate heat stress in the city. “They don’t have cooling stations everywhere…it’s hot everywhere.”

Scientific journal GeoHealth recently published a report detailing the number of heat-related health emergencies and the inequitable effects of urban heat exposure in Virginia’s capital city.

Researchers found Black people in Richmond have experienced disproportionate heat-related illnesses during the warmer months of the year, while communities they live in have historically received little investment to help them keep cool.

“While human-caused climate change is driving average global temperatures to rise, some communities and neighborhoods in Richmond, Virginia experience hotter temperatures than others,” the research paper stated, largely due to a pattern of government disinvestment in Black and low-income neighborhoods. “Hotter, less resourced neighborhoods experience more heat-related health emergencies like heat stroke and heat exhaustion.”

The research relied on Emergency Medical Services data reported to the Virginia Department of Health that found there were 492 heat-related incidents between May and September from 2016 to 2022.

Of those, Black or African-American patients counted for 306, or 62% of the incidents, despite comprising only 39.9% of the city’s population. Conversely, white patients made up 32.9% of the incidents while comprising 42% of the population.

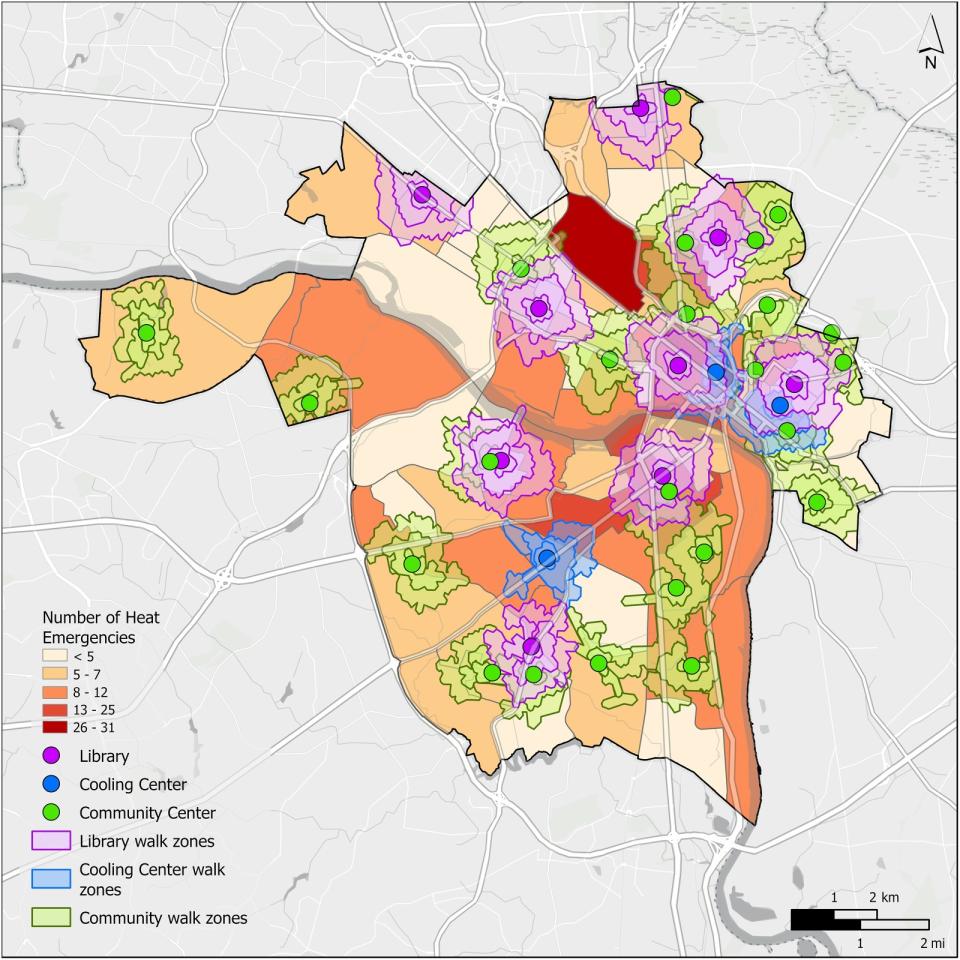

The research also mapped the city’s cooling centers, which include nine libraries, and three centers that are opened when temperatures rise above 95 degrees.

About 53.9% of the heat-related illnesses occurred within a 1.4 km, or .8 mile, walk of the centers, the report found — a distance that takes about 15 minutes for a fast walker to cover. Opening the city’s 24 community centers as additional cooling stations would put another 17% percent of the heat-related illnesses within that 1.4 km walking radius.

“Spending just a few hours at a cooling center can help prevent heat-related illnesses, but a lot of Richmonders might not know these cooling centers exist or they might not have a safe way to get there,” said Peter Braun, one of the researchers and a built environment policy analyst with the Richmond and Henrico Health District. “In some neighborhoods, if you have to walk down a street without sidewalks or shade from street trees or if you have to wait at a bus stop without a shelter, you’re going to be exposed to extreme heat.”

Jeremy Hoffman, another of the paper’s researchers and director of climate justice and impact at Groundwork USA, said having access to cooling options, “is a matter of life and death.”

The research also reviewed the locations of the Greater Richmond Transit Company’s 1,618 bus stops, of which 5% have shaded shelter. Just under 200 of the heat-related incidents happened within 100 meters of a bus stop. The bus company is offering zero-fare service for their air conditioned buses, Hoffman noted.

The findings build off work by Hoffman in 2020 that studied the effect of past housing policies on urban heat islands. Southside Richmond, an area Hoffman said lacks historical investment in sidewalks that could help people get to cooling centers, only has one such location on Hull Street. Last year, Hoffman had published research that found cooling centers around the state were sparsely located.

Protections for people working outside have also gained attention this summer season. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration recently released draft rules that require companies to schedule breaks for people who are working outdoors. The Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental nonprofit, called the rules a “crucial step forward.“

“Workers in our nation should not be denied something as simple as a water break or a few minutes to regroup in the shade,” said Juanita Constible, a senior advocate in the environmental health program with NRDC. “That’s just basic human decency. It shouldn’t be controversial.”

The post Research shows heat exposure disproportionately affects Black Richmonders appeared first on Virginia Mercury.