A Sacramento homeless shelter evicted these three moms. Their children pay the price

One week after a Sacramento homeless shelter evicted Brittany Anderson and her two young sons, she managed to take her older child to school.

Every drop-off and pickup since the eviction had been an ordeal. But the smiley Britain, who was 4 when they were forced out of the shelter in February, loved his pre-K program at Suy:u Elementary School in Fruitridge Manor. With no place to stay and everything going wrong, Brittany, 36, was clawing to keep something steady for her little boy.

During the Anderson family’s year-long stay at the city-funded hotel, she could easily take Britain to class in the morning: They had a steady place to stay, right near campus. Yes, it was infested with roaches, but they could get a decent night’s sleep.

In February, she was kicked out of the program. She was told she had violated the rules. A spokesman for the city, Tim Swanson, said that all evicted families “received multiple notifications and warnings prior to the exit decision.” Brittany said her rules violation occurred when she tried to break up a fight in the hotel’s common space and was punched in the face.

Suddenly, she and her kids had no stable place to live.

After the eviction, Brittany bought an inexpensive car so at least she and the boys would have a solid roof and walls. It immediately broke down. Britain started missing school because Brittany, wandering around all night or working graveyard shifts at a part-time concierge job she was desperate to hold on to, often had no way to get him there.

The mother was exhausted. On Feb. 15, she was slumped at a Taco Bell so cold you could see her breath, nodding off in her chair despite the chill. Britain and the baby, Brandon — then almost 6 months old — had spent the previous night with a friend of Brandon’s father. The friend didn’t have space for Brittany, though, so she spent that winter night walking around Elk Grove trying not to freeze. That was the second night in a row she hadn’t slept. The night before, she worked a graveyard shift.

She had nowhere to go. She could barely keep her eyes open. And it was almost time to pick up her 4-year-old from school.

She took a deep breath and stood up. She trudged to the low-slung building where Britain was a student. The cheerful boy skipped out of his class and played outside the school’s front office, where Brittany had left her phone to charge. Britain hopped onto a brick bench. He chirped about his day.

That evening, the little boy could go back to the family friend’s place along with his baby brother. But Brittany wasn’t sure where — or whether — she would sleep that night.

The uncertainty took a toll on her and the boy. A few months after they were kicked out of the shelter, Britain was expelled from the school he loved for missing too many days.

The Andersons are just one family that was churned out of the Sacramento shelter system and back onto the streets. When the shelters evict parents, their children become collateral damage.

A tale of three families

The Sacramento Bee followed three families evicted from city shelters in February: Brittany and her two sons; Tanika Williams, her husband, Michael, and their two daughters, now 18 and 3; and Jessica Rose, her husband, Stewart, and their 11-year-old daughter, Faith.

Months after the evictions, all three families were still homeless, and all three bounced between hotels and the street with minimal support from social services. Along with Brittany’s son, Tanika’s teenager left school.

Their stories reveal the complications of assessing homelessness in Sacramento.

The most recent federal homeless count, using a methodology that differs from previous counts, found a 41% drop in unsheltered homelessness in Sacramento compared to 2022. Several local service providers and advocates said the reported decrease was unbelievable, but officials celebrated the results.

“The steady course we set seven years ago to address this state and national crisis is working,” Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said at a news conference.

Tanika, however, said the city’s approach to homelessness was a failure. And her family, along with Brittany’s and Jessica’s, showed that even when the city gets people indoors, they may end up back on the streets. Tanika said she hadn’t seen many people make it out of the shelter and into something good.

The city motel program, Tanika said, “was supposed to be for people to get on their feet with income, permanent housing, some kind of direction, or whatever services that they offer,” she said. “That didn’t happen.”

That is borne out in data the city provided to The Bee to “highlight the success” of the motels. Sacramento funds six former hotels that shelter up to 200 families each night. Julie Hall, a spokeswoman for the city, said that in the past year, 1,283 individuals were served in city motels, and 193 moved into permanent housing — 15% of the participants. An additional 46 individuals, she said, left for “positive destinations.”

Other motel residents, like the Williams family, left for less positive destinations.

“I’ll tell you, some of the participants that were there with us are still on the street,” Tanika said. “And they’re doing worse than we are.”

Sacramento spokesman Swanson said in February, “If an involuntary exit is unavoidable because a participant has violated the agreed-upon guidelines multiple times, the city will work with them to find alternative shelter, especially if children are involved.”

In accordance with that policy, two of the families received and accepted offers for temporary shelter from the city after the evictions.

But they said that when they did accept shelter, the families were sickened — in one case, literally — by the conditions. Brittany felt dehumanized when she had to take her then-4-year-old to the bathroom in an outdoor toilet in the dead of winter. Faith caught RSV when the family was essentially given three cots in a shelter foyer.

All of the parents were fraying.

Leave the Barbies behind

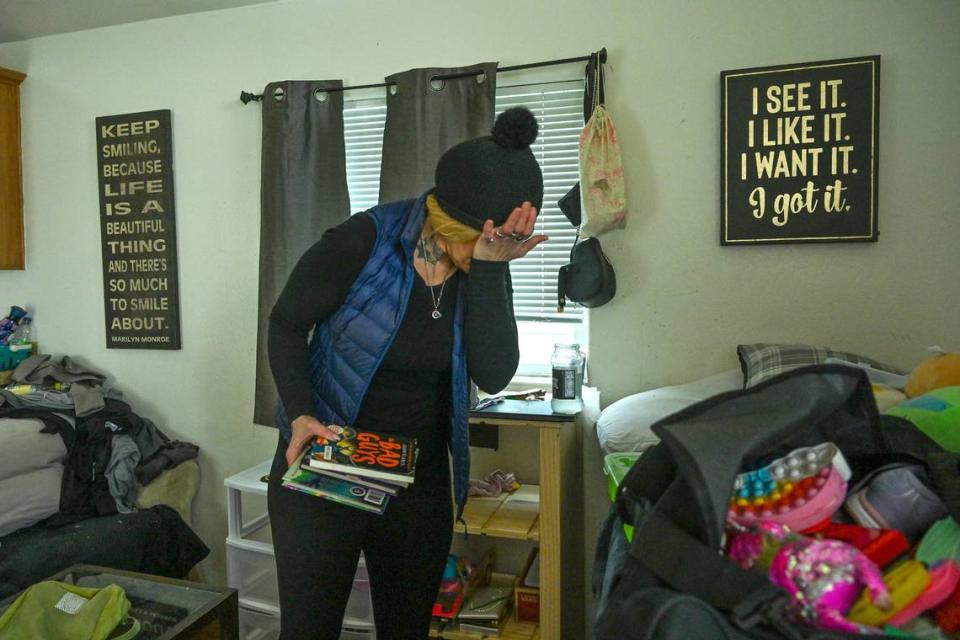

On Feb. 16 — the day Jessica had to vacate her cottage in North Sacramento — she was frantic. Standing outside the little home, she grimaced as she apologized for the disarray.

Normally, she is obsessed with order, but there was nothing normal about Feb. 16. Until that morning, Jessica said, she hoped that because she found a new home for the beloved pet bunny who was one ostensible rules violation, the family would be allowed to stay in the shelter where they had lived for a year.

She was wrong. A property manager who was by turns exasperated and sympathetic

told her the police would arrive at 1 p.m. to make sure Jessica and her family were off the premises.

In her rush to pack, she couldn’t take everything. Jessica had to triage: Which clothes would they abandon? What art, and what kitchen supplies? Which of her daughter’s toys were important, and which could they leave tucked under the twin bed?

Faith, her 11-year-old daughter, was playing on the property with a friend while Jessica tried not to panic.

“My kid is resilient,” she said. “I told her, I promise I’ll keep her in her school. That’s what she’s worried about, is school. She kind of avoids conflict, or avoids when something’s going on like this. She gets quiet, and she’ll just play.”

Jessica looked at her child’s toys. The Barbies could stay behind, she decided. The L.O.L. dolls would come with them. Faith loved those.

Eviction-level violations include a bunny and a piece of mail

Jessica kept extensive records of the conditions in Arden Acres. “I know that people wouldn’t believe the story, so I just out of habit document everything,” she said. “But it never really pays off.”

She took multiple photos of large mold patches on walls and ceilings and submitted formal complaints to the program over several months.

She also showed The Bee written notices she received for her family’s alleged rules violations.

On Sept. 15, she received a notice of a violation for not moving out of her unit promptly enough. On Sept. 19, she received a write-up for leaving items on the porch (she said she did leave her items outside, but only because she was waiting for the unit to be treated for a roach infestation). On Oct. 20, she was written up for her bunny hopping around the property (she said it was another resident’s bunny).

The strangest notice came on Oct. 5: She violated the rules when she received a piece of mail at the property.

The envelope had contained a bill for the ambulance that took Faith to the hospital when she started having trouble breathing.

After the eviction, while the family holed up in a motel near the McClellan Industrial Park, Jessica also collected screenshots documenting her apartment search. The screenshots show she made inquiries to 61 apartments and applied to 23 in the six weeks after she was “exited” — the term that city officials prefer — from the tiny cottages. Jessica secured an emergency hotel voucher, but the voucher expired. She said she received a short extension because she had been trying so hard, but then that extension ended, too. Despite all her efforts, she still had no home.

Jessica considered it a blessing that a friend agreed to sell her a gold Acura for a few hundred dollars — the family of three, she knew, would have to sleep in the SUV.

She said when they couldn’t pay for the motel anymore, they moved into the car. They lived on Roseville Road briefly, where their tiny puppy bolted outside and got hit by a car. On April 19, she said it had been “hell.”

A week later, after spending too much time in the car and feeling it get smaller and smaller, Jessica was planning for the future by trying to acquire a tent.

“It’s like the harder I try, the more I work, the more I’m let down and pushed aside,” she said. “The saddest part is, my daughter sees it, too. She has more hope in Cal Lotto than these programs.”

Faith had been needling her mom to buy lottery tickets.

Jessica could not be reached for a comment in mid-June. Previously, she had said it was almost unbelievable how many hurdles she had to clear, just to end up back on the side of the road. The system, she said, had been “cruel.”

A mother in despair

Brittany — between caring for her baby and battling postpartum depression — could barely keep food on the table. The future was a luxury she could hardly imagine, much less afford.

In May, she sat on the curb outside the overcrowded apartment where she was staying with a friend. He didn’t really have room for her and the boys, and she wasn’t sure how long their stay would last. Britain fussed with her phone nearby while she described her own hopelessness.

“I feel like I’m stagnant,” she said. “And I am. I’m just getting by for the next day.”

The mother felt abandoned. She said that she had been in sporadic touch with her case worker at CalAIM — a Medi-Cal program that, with a broader view of health, addresses poverty. But she added that local government representatives had not contacted her in months.

Other than loved ones, she said, the only people who had checked in on her were Bee reporters.

She was trying so hard to get back on her feet — to get back the $1,100 monthly cash assistance that was canceled because she couldn’t get her mail when she was living on the street and she missed a renewal notification; to make more money; to achieve some kind of balance in her life. She yearned to somehow make enough income to get an apartment of her own, where she and her boys could have a little peace.

In the overcrowded unit with her friend, his roommate and her sons, she was falling into despair.

“I’ve been needing to cry sometimes, and I have to just —” she sat up straight, quickly sucked in air and closed her mouth tight. She had to hold it in “because I can’t cry in front of the kids. Then my son gonna be like, ‘Mom, what’s wrong?’”

She lowered her voice, and said the answer to the question was “I feel like jumping off of the roof right now.”

A demand for a clean room, a rule violation

The Williams family read on a document that they were terminated from the shelter program on Dec. 5, 2023, though Tanika said she didn’t realize it at the time. Like all residents in the motel, they had to move to a new room every 21 to 28 days. After dealing with moldy, cockroach-infested rooms, Tanika said, they asked more strongly that the new room be deep-cleaned before they moved into it.

The city said that it investigated complaints about the motel’s habitability and found only minor maintenance problems that were quickly rectified. Tanika said that in addition to mold and roaches, her heater broke in the middle of winter and wasn’t fixed promptly, leaving her, her husband, their teenage daughter and their then-2-year-old, Makhila, freezing.

So, in December, they hunkered in their room and waited to hear about the deep cleaning.

On Feb. 14, they were kicked out of the motel where they had lived since June.

They had a van, which was more than some people had. It was raining the night the cops showed up to escort them off the property, and Sgt. Zachary Eaton said the Sacramento Police Department paid for the family to stay in a Motel 6. Their belongings were still locked in the room, as was the fish, Bluez. They returned the next day to retrieve their things, some of which had been dumped outside. Someone had unplugged the fish tank and left Bluez on a little table by the door, possibly overnight, Tanika worried.

He was lethargic, but alive.

Tanika and Michael did not want to enter a congregate shelter: Michael has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their now-3-year-old, Makhila, has sickle cell disease, putting both of them at higher risk for illnesses that can spread in crowded settings.

The police only paid for one night in the Motel 6. Over the weeks after the eviction, the family scrambled to find vouchers or to pay for motels.

Despite everything, Amaya, the teenage daughter, was going to Sacramento City College and working at a restaurant. The girl was ambitious. She was using her paycheck to help her family scrape by.

For a few weeks, the family made it work in motels. On March 1, Amaya was sitting in the van outside a Quality Inn in Elk Grove, doing her homework.

Three weeks later, she had quit her job and left school. The family drove to San Bernardino County, where Tanika said an NAACP advocate told them they might have a better shot at getting services. Their car broke down on the way, and they lost their one makeshift shelter.

The city of Sacramento, Tanika said, had failed her. The Williamses have spent most of the last three months living in the spare bedroom of a good Samaritan who knew they had spent a few days sleeping on a sidewalk in San Bernardino County.

Tanika had been optimistic when she moved into the Greens on Stockton. She and her husband had lost their jobs and their housing early in the pandemic. They moved to California to be closer to his family. They were able to work, Tanika said, if the rest of their lives could get in order.

“Especially as a two-parent household,” Tanika said, “my family should have been out of the system a long time ago. ... You can’t keep shuffling people around. You’re not housing nobody.”

The system, it seemed to her, had warehoused them and thrown them out with nothing to show for it. On a few days this spring, she had no way to give her baby girl a bath.

She had a word for what the shelter system had done to her family. She called it “fraud.”