How SLO activist saved Cuesta Canyon from being ‘buried alive’ by highway project. ‘Why not?’

The Cuesta Grade road has been a perpetual work in progress since the first shovel full of dirt was tossed.

But there was one plan that went too far.

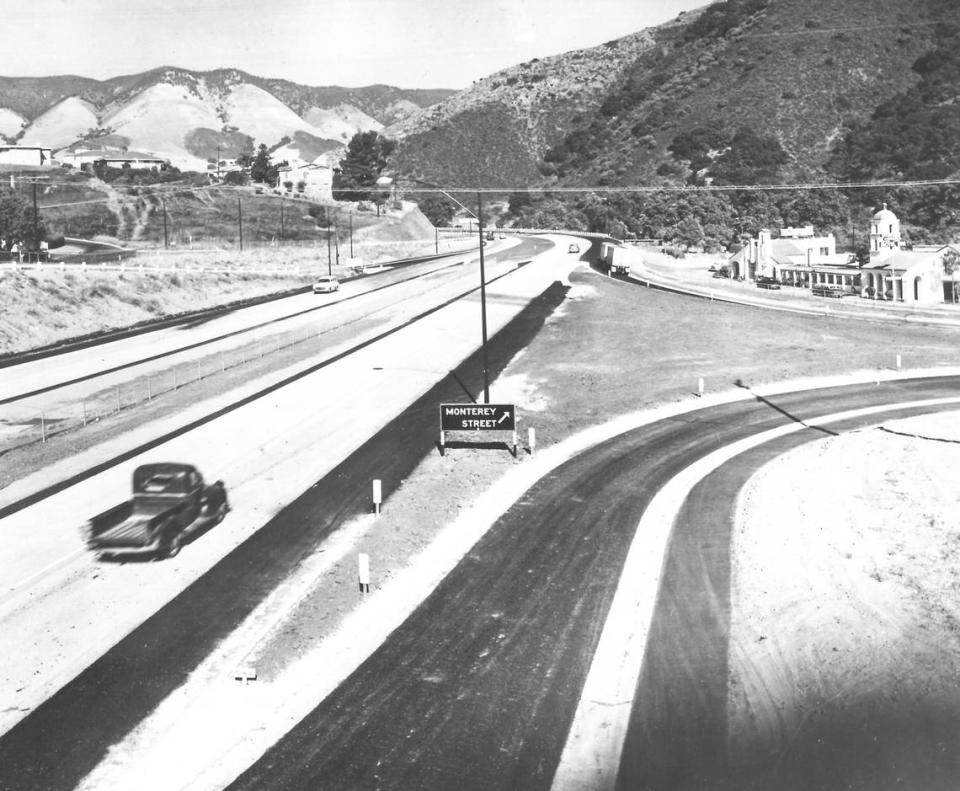

As construction technology and vehicle design advanced, various road routes evolved from walking path along the creek, to horse-drawn wagon road, to railroad, to paved road and finally, to multi-lane highway.

An Oct. 9, 1967, story in the Telegram-Tribune said the California Division of Highways planned a massive rerouting, moving the road to the west side of the canyon, nearer the railroad. The plan filled most of the canyon with earth excavated from the pass.

The new road would be freeway and the old one would revert to being a secondary county access road.

Engineers said the new route would solve east-side rock slide and drainage problems. So much earth would have been moved that the six-lane freeway’s climb would have flattened the grade incline from 7% to 5%.

In some places the canyon’s sycamores and oaks would be buried under fill dirt 200-feet deep and pave much of the Miossi property, La Cuesta Ranch, much of which is today the Miossi Open Space hiking area.

This did not sit well with ranch owner Harold Miossi, so he began a campaign to stop the bulldozers.

He died in 2006 at the age of 84 and Harold J. Miossi Charitable Trust is now associated with a host of philanthropic causes.

Miossi’s legacy of environmental activism was documented in the following Nov. 15, 1993, story by Ann Fairbanks.

Archives preserved

In the mid-1960s, the state Division of Highways wanted to chop 160 feet from the top of Cuesta Grade, bury the canyon and creek below with 38 million cubic yards of dirt, plant a six-lane freeway and 120-foot median, and ram it through “a land of lavender hills and shadowed oaks, maples and sycamores, meadows and old barns.”

That lyrical description of Cuesta Canyon in the Feb. 25, 1968, issue of the Los Angeles Times is still apt today — thanks to the rabble-rousing, letter-writing and alliance-building of Harold Miossi.

“They wanted to make a grapevine of Cuesta Canyon,” said Miossi, who still lives in the canyon ranch house where he was born 71 years ago. “When I saw the plans, I just sat there in total disbelief.”

He didn’t sit there for long. Then best known as a political workhorse for Democratic candidates, Miossi turned into an activist. He took on Goliath, defended his native canyon, and won his first environmental battle.

The letters, photographs, display materials, official records and publications documenting that battle — as well as many later ones — will comprise the backbone of a new collection to be housed at Cuesta College.

The San Luis Obispo County Environmental Archives will serve as a repository of fragile materials and documents historically significant to the county’s environmental movement.

The core of the archive’s collection will be more than 100 boxes of materials amassed by Miossi and three fellow “harbingers of conservation causes” who spoke and wrote prolifically:

• Kathleen Goddard Jones, 85, of the Nipomo Mesa, a leader for 30 years in the fight to preserve the Nipomo Dunes and a recipient of a national environmental award.

• The late Lee Wilson of Arroyo Grande, who was instrumental in winning federal wilderness status for Lopez Canyon and served as the first president of the local Sierra Club chapter.

• And the late Ian McMillan, a Shandon rancher and author who fought the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, campaigned against the devastation of the San Joaquin kit fox, worked to save Morro Rock and battled the desecration of nature for more than 50 years.

“Together they took actions that really preserved a good 10% of this county,” said Dominic Perello, chair of the Environmental Archives Committee.

A former chair of the Sierra Club’s Santa Lucia chapter, Perello has been active himself in environmental issues since moving from Santa Barbara to San Luis Obispo in 1954 to teach at Cal Poly.

“When I came to San Luis Obispo it reminded me of Santa Barbara in the 1930s,” Perello said. “By the time I graduated from UCSB in 1954 to teach at Cal Poly, I had found we were growing up like L.A.

“Now in San Luis Obispo, we’re about where Santa Barbara was in 1945-46. Everyone wants to build more, further up the hills.”

As head of the archives committee, Perello is anxious to preserve what Miossi calls “irreplaceable footnotes to our county’s history” documenting the beginnings of the still-ongoing fight to keep San Luis Obispo County pristine and natural.

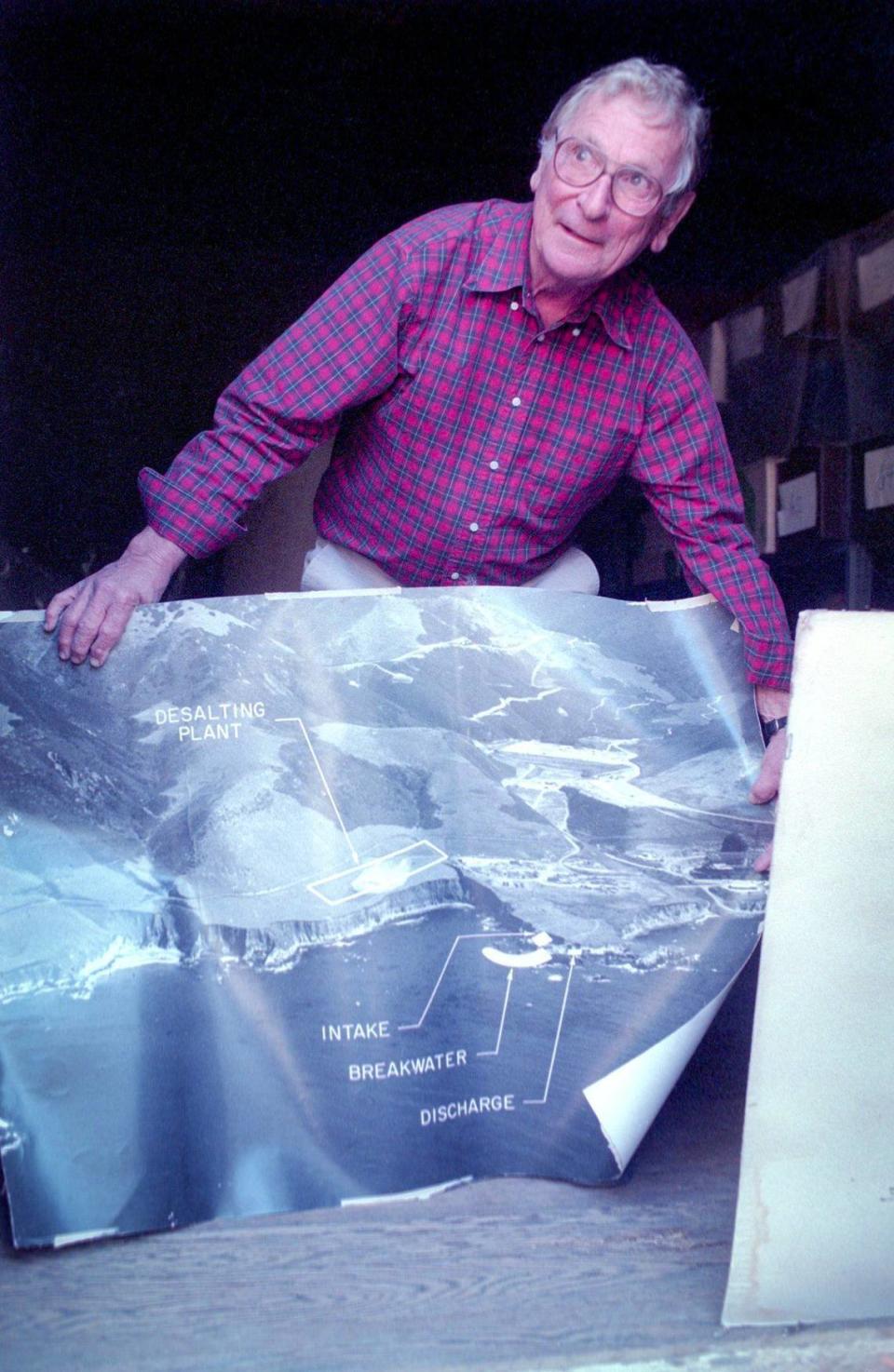

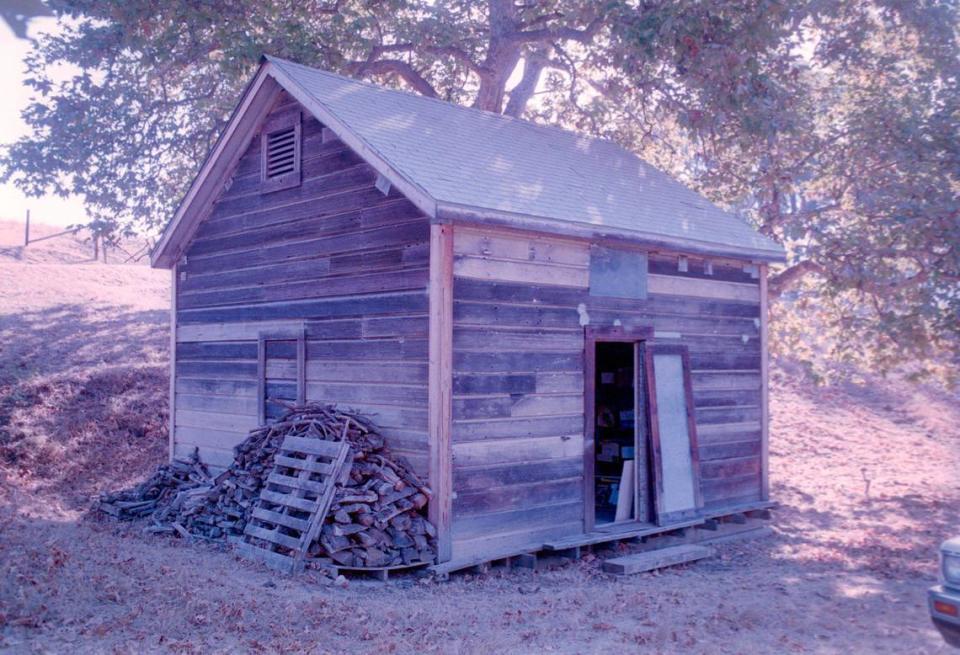

During a recent visit to the Miossi family ranch that would have been obliterated by the massive realignment of Highway 101, Perello joined Miossi in sifting through his 10 boxes of historical materials stored in a granary.

Built in 1890 out of cheese boxes, the 20-by-20 foot building is nestled among oaks and sycamores that dot rolling hills threatened in years past by wildfires.

That’s why it’s so important to gather such collections, Perello and Miossi agreed, and secure them for future generations in a place safe from the ravages of nature and time.

Take the collection of someone like Ian McMillan, whos writings and photographs occupy about 80 boxes.

“His children are very eager that it be preserved,” Miossi said, “but future generations may not be as dedicated.

McMillan was a “great friend” Miossi said, who used to call him on Sunday mornings to talk about the kit fox or whatever cause was on his mind. Then two or three days later, McMillan would follow up the discussion with a letter in the mail.

In a 1972 letter to the Telegram-Tribune editor, McMillan praised his fellow conservationist Miossi.

“…Traveling north past the Miossi Ranch in Cuesta Canyon, what always impresses me most is the historic canyon itself and the thought of how it was so ably defended a few years ago from being buried alive by a monstrous highway project. I will never forget that historic battle in which the local forces of conservation under the leadership of Harold Miossi, combined in what should stand as the greatest conservation achievement so far in the history of our county.”

In Miossi’s collection — which includes aerial photographs of the county’s coastline before Diablo Canyon, yellowed newspaper clippings, piles of manila folders stuffed full of documents, photographs of rolling hills now submerged by Lopez Lake — there are several 8-by-10 photographs of picturesque Cuesta Canyon.

Attached to each photograph is a watercolor overlay by Peg Maxwell, a retired San Luis Obispo High School art teacher. The overlays graphically portrayed her concept of what the Division of Highway’s “scenic corridor” would do to the canyon.

According to a 1981 article in California Today, those visual aids proved to be a “crowd-pleaser” when the battle for Cuesta Canyon hit the County Board of Supervisors, which had to approve closure of Cuesta access roads before the highway would become a freeway.

“Thanks to Miossi’s careful planning, the highwaymen were underdogs in their own town,” the article reads.

When the retired art teacher presented her watercolor overlays, “the audience laughed and applauded wildly. At the close of testimony, Board Chairman Hans Heilmann asked if anybody was in favor of any of the routes proposed by the Division of Highways. Not a hand was raised. Unanimously, the board voted not to approve any of the routes. Applause broke out.”

Miossi’s cause hadn’t always been so popular, though. His was a lone voice, he said, until he captured the attention of the Los Angeles Times and landed on the front page that Feb. 25, 1968.

Until then, he said, his campaign had been wildly written off as “just the mouthings of a pitiful creature.”

But thanks to those “mouthings”—along with the vision and dedication of people like Jones, Wilson and McMillan — much of San Luis Obispo County’s natural beauty has been saved from man’s intrusion.

![OLD CUESTA ROAD–A photo from the California Division of Highways [now Caltrans] which once reported 71 hazardous curves on the highway north of San Luis Obispo. The dirt road was built to replace Stage Coach Road in 1915 and improved in 1923, the photo is from about 1922.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/aLL2WJYyN6A_FAlP2rMKnA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTI5Ng--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/san_luis_obispo_tribune_mcclatchy_articles_722/6fc18976304bb78cec705e7759f9837b)

Those conservationists “cringed that our beautiful county might fall prey — with polluted air, valleys paved over, mountains leveled, indigenous flora and fauna wiped out, dunes and shoreline commercialized,” Miossi wrote as part of a description of the archive project.

“Rather than wring their hands and say ‘Why? Why?’ they dreamed of a landscape that could be saved and said ‘Why not?’

“That is why we seek to assemble their materials in a central safe location where we — and generations after us — who seek to preserve this county’s pristine image can learn from the past.”