State kills hundreds of deer at North Texas ranch, after years of legal fights

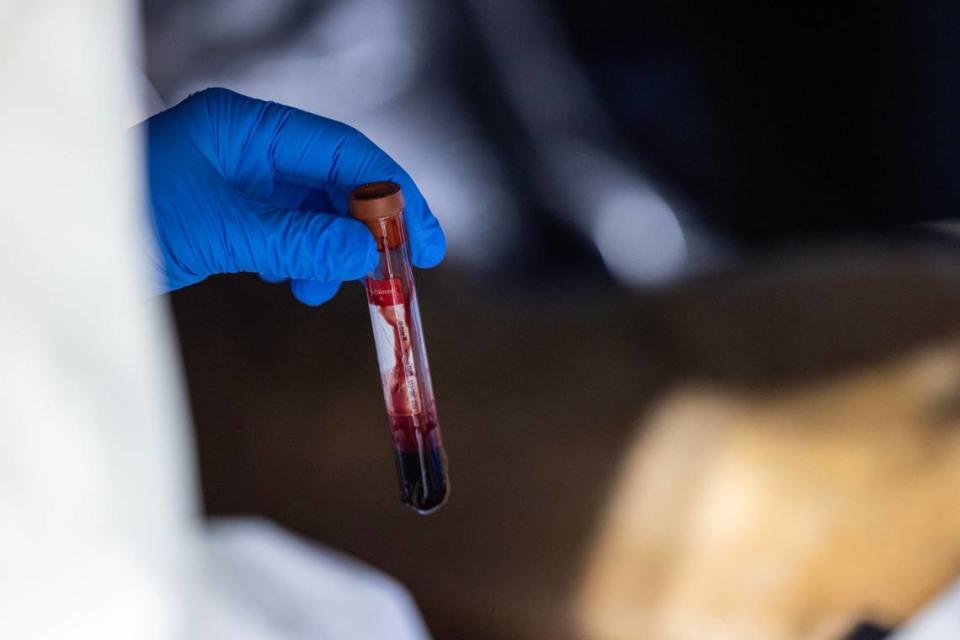

The blood, it seems, is everywhere.

Splattered on the covered boots of the biologists. Pooled in the folds of the massive black tarp on the ground. Smeared across the bodies of the dead whitetail deer lying in orderly rows.

It’s past 10 p.m., but bright lights tower over the improvised field laboratory, bringing the operation into near-daylight brightness.

A generator thrums the air, a constant backdrop to the quiet work of about 50 state biologists. The workers, wearing matching all-white or all-blue biohazard suits, are a blur of coordinated motion, moving deer from one place to the next.

The deer, the former inhabitants of RW Trophy Ranch in Hunt County, were killed by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, in order to manage a highly contagious deer-specific disease called chronic wasting disease. Parks and Wildlife staff have said in legal filings that the outbreak is the largest the state of Texas has ever seen.

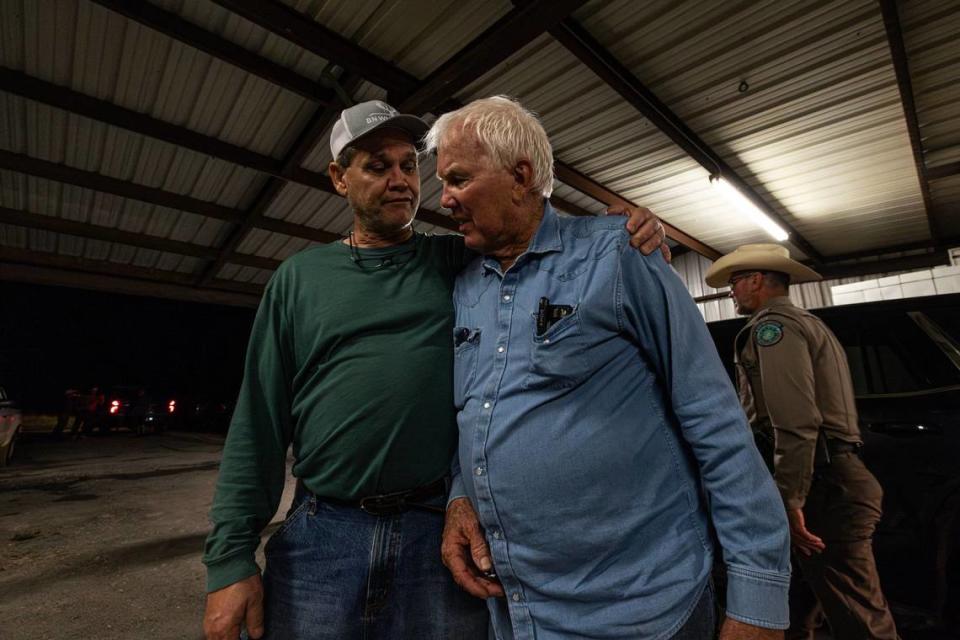

Robert Williams, a whitetail deer breeder for four decades, has spent years fighting the state’s order, even as the department reported more and more CWD cases on the ranch. Williams, 85, says he isn’t done fighting. He plans to continue his long-standing lawsuit, and maybe file more suits, too.

But the killing of his herd, on Tuesday night, was an ending of sorts.

Williams walks away from the field laboratory, from the bodies of the deer he spent years raising. He’s backlit by the bright stage lights, the generator still humming, a slight chill in the air left behind by the storm system that pummeled the state in the previous day.

“Well,” he says, into the darkness, to no one in particular. “I lost.”

The legal battle

The first positive CWD test on Williams’ farm came from a routine testing, after a deer died in the February 2021 freeze.

Texas whitetail deer breeders are subject to a host of testing requirements, put in place by the state to track and contain CWD spread. The disease is a major threat to breeders, who spend years selectively breeding their deer to produce bigger and more aesthetically pleasing bucks, which are then sold either to other breeders or for trophy hunting.

CWD is an always-fatal neurological disease. It’s essentially the deer version of mad cow disease, although there are no known cases of CWD jumping from deer to humans.

The state Parks and Wildlife Department takes positive cases seriously, in an attempt to keep the disease under control and prevent it from spreading to other deer herds. In Williams’ case, the rancher and the department couldn’t agree on a disease management plan. Instead, in spring 2022, the department issued a full depopulation order for the farm.

Williams and his attorneys sued the state, claiming the department was overreaching and had no right to kill the deer. Legally, though, the deer didn’t actually belong to Williams; under Texas state law, whitetail deer are considered wild animals and, as such, belong to the state even when they’re held in captivity and bred by ranchers.

Over the course of two years, the legal case wound its way through several courts, including the Texas Supreme Court. The hearings, which have so far focused on whether the state can depopulate the ranch even as the court case is ongoing, were sometimes dramatic. At one point, state workers were en route to the farm to carry out a depopulation, until a last-minute court order stopped them in their tracks and prevented them from entering the property.

In mid-April, after months of back-and-forth, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the Parks and Wildlife Department can go onto Williams’ ranch and kill his deer. Texas Sen. Bob Hall, R-Edgewood, along with the Texas-based Deer Breeders Corporation — of which Williams is a board member — submitted documents in support of the rancher, but to no avail.

Parks and Wildlife staff, along with other organizations that are in favor of the depopulation, describe the process as an unfortunate necessity.

In a November legal filing, the state wrote that RW Trophy Ranch “now hosts the worst-ever CWD outbreak in Texas.” In a mid-March filing, the department notified the state Supreme Court that there had been 208 positive CWD cases at the ranch over the previous three years. Parks and Wildlife staff said this week that the number continued to rise, and reached 254 by Tuesday morning.

The Texas Deer Association, a professional organization and lobbying group for deer breeders, penned an April letter in support of the depopulation. The letter, co-signed with the Texas Wildlife Association, marks a shift for the deer association, which opposed the killing of Williams’ deer shortly after the first positive was found.

Kevin Davis, the executive director of the Texas Deer Association, said the disease was too far out of control at RW Trophy Ranch.

“If we truly market ourselves as science-based and part of a long-term solution to CWD, then we also have to understand that some situations can be unsalvageable,” Davis said.

While the association lobbies on behalf of deer breeders, that also means taking into account what’s best for the entire industry, Davis said.

The outbreak at RW Trophy Ranch has shown just how bad CWD spread can be, said Jody Phillips, the president of the Texas Deer Association.

“If you have a problem that exists at your farm, you can’t turn a blind eye,” Phillips said. “As an industry, we’ve all learned from this.”

The shooting

Williams and his daughter, who manages the ranch, didn’t want their deer to be shot.

They didn’t want them killed at all, of course, but they would’ve preferred the animals be corralled and euthanized rather than shot with firearms. But the state Parks and Wildlife Department determined shooting was the most effective method. And, under a state law passed last year, the department will cover the cost of a deer depopulation, but only if the department conducts the depopulation itself.

That means Williams would’ve been left with the bill if he had opted to euthanize the deer on his farm.

Instead, Williams and his daughter euthanized just three deer on Tuesday. They darted and put down two bucks — 15-year-old Monarch Supreme and 13-year-old Bambi Remington — plus a doe named Amethyst. They couldn’t bear for those three, favorites of the family, to be shot.

When the state workers began arriving at RW Trophy Ranch on Tuesday afternoon, Williams was clear — with the media, with his senator and with workers themselves — that he didn’t want them there. But he didn’t have a choice. Under Texas state statute, the biologists and wardens carrying out the operation had a right to enter his property to manage the outbreak.

Williams’ ranch spreads across hundreds of acres and includes numerous houses and other buildings. The Williams family and friends were stationed on Tuesday at the lodge, just outside the safety zone enforced by Texas game wardens.

The deer pens were across a field from the lodge, blocked from view by a stand of trees but still within hearing distance. The shooting started shortly before 7 p.m., and then stopped for a long stretch.

The group at the lodge puttered around. The storms from earlier in the day had left the evening air cool. In the field around the lodge, as dusk fell, a wren sang. From somewhere else in the high growth, cicadas buzzed.

And then, the shots began again.

There was nothing to do but wait. Williams, as the property owner, was allowed closer to the pens, accompanied by a game warden. He left the lodge for a while and, when he came back, his guests crowded around him and listened for updates. Williams ranted, in short bursts, about the overreach of the state.

As the last of the day’s light left the sky, someone started a bonfire. Hall, the senator, asked if he could take home some antlers for his golden retriever to chew on. People milled about outside, eating pizza and swatting at mosquitoes.

Originally, Parks and Wildlife staff had said the shooting could continue through the night. But by 10 p.m., word came up to the lodge that the depopulation itself was over. The 250 deer left on Williams’ ranch were dead.

The dissections

With all the deer dead, Williams and his many guests — including the media and Hall — were allowed to watch the state biologists process the bodies.

The state’s temporary field lab was set between the deer pens, a short drive down the dirt ranch road. Williams and his entourage, plus state game wardens, parked at the gate of the pens and walked the rest of the way in the dark.

Still a little ways from the setup, a sharp smell — like pool chemicals — tinged the air. Two shallow dishes set on the ground came into view, a scrub brush laid nearby and a bottle of bleach sat off to the side. A little further along, the bleach smell gave way to something else — something earthier, mustier. Something like blood.

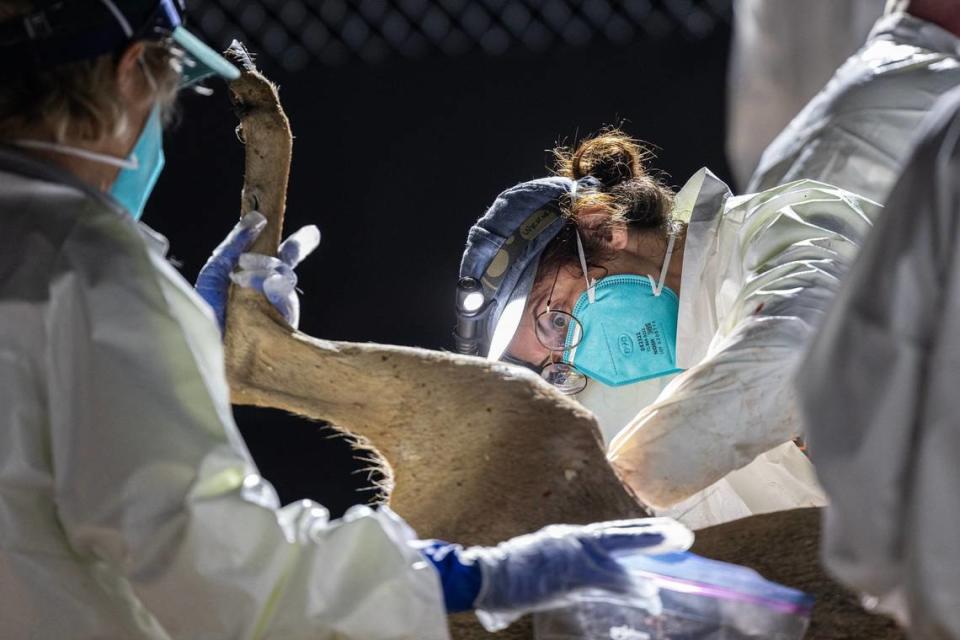

The staging area itself was lit bright as day, visible from across the ranch in the dark. A wide swath of the muddy ground was covered in thick black tarps, with about 15 deer bodies laid in neat rows in the center. Trailers — covered in the same thick black tarps — backed up to the staging area, with four wooden tables set directly in front of them.

The state biologists, in their plastic protective gear and double gloves, moved smoothly, efficiently, gathering around the dissection tables and the trailers.

As the biologists worked, Williams and some of his guests — including Hall’s staff — circled the tarps and took video. Some of them reprimanded the staff for participating in the depopulation. Williams at one point called his attorney and then asked to meet the wildlife veterinarian on the scene. The workers — with the exception of top staff who spoke with Williams — largely ignored the commotion; they hauled deer bodies around, made quick cuts with scalpels and spoke to each other in quiet questions and answers.

The process for each deer went like this: Three workers grabbed a dead whitetail deer from the line, one carrying each set of legs and the other carrying the head. They hauled the animal onto a wooden table, and a team cut up the animal precisely, gathering a prescribed set of samples.

Each ear, cut from the body with the tags still in place. A vial of blood, from a slice to the neck. Two lymph nodes, from the throat. A specific portion of the brain stem, called the obex. A whole eyeball.

And then state workers hauled the deer body off the table and into the back of the trailer. The workers repeated the process about 250 times, an efficient dissection for each dead deer. The state workers expected to fill five trailers with deer carcasses, which were later hauled away to a landfill equipped to dispose of biohazard waste.

The original plan — according to the state Parks and Wildlife Department’s big game director, Alan Cain — was to haul the trailers to a landfill in the Terrell area, near the farm. But the storms had flooded the landfill, forcing the department to instead drive the bodies to a landfill near Waco, about a two-hour drive away.

A total of 68 staff were on the ranch to process the deer bodies, according to a Parks and Wildlife spoksperson. Cain said the department called in a large number of workers in part to speed up the work. The biologists didn’t want to be conducting a depopulation any more than Williams wanted them on his property, Cain said.

“You didn’t become a wildlife biologist to do this,” Cain said. “None of them want to be here.”

The last of the Parks and Wildlife workers left the ranch at about 3:30 a.m. on Wednesday, Cain said. The operation took more than 12 hours and, by the end, the Williams ranch was emptied of deer.

Out of business

On Tuesday, as the day dragged into evening and then night, Williams didn’t say how he was feeling, exactly.

He said, first, that he’s already dug a new pond on his ranch property, using a bulldozer that he likes to drive himself. In the aftermath, with his herd gone, he thinks he’ll spend a lot of time fishing. Bass, mostly.

He said he’s been having a hard time sleeping. He said his blood pressure has been high, and that his doctor ordered him anxiety medication. He said he hates the Parks and Wildlife staff who killed his deer, even more than he hates President Joe Biden, and that he’s told them so, too.

He said he isn’t a crier, not around other people, but he might have a moment once he’s by himself.

The next day, Williams said in a phone interview that the reality of the depopulation had started to sink in. He drove out to the empty deer pens on Wednesday, he said, and regretted that he hadn’t let the deer out of the pens before the state got there.

“It made an old man cry,” he said.

He felt “furious,” he said, at the state and at the way his deer were killed.

George Courtney, the vice president of the Texas-based Deer Breeders Corporation, said he spent hours with Williams on Thursday, and could see that the reality of the depopulation was beginning to set in.

“This is the first time in 40 years the man hasn’t had deer,” Courtney said of Williams, who he called “one of the forefathers” of Texas’ deer breeding industry.

And now, after four decades, Williams said he used to be — heavy emphasis on the past tense — a whitetail deer breeder.