Strong arms, big feet: NC State paleontologists discover a digger of a dinosaur

99 million years ago — after the Jurassic dinosaurs but before the T-rex — a 7-foot dinosaur with freakishly long feet, teeth serrated like a steak knife, and strong, sturdy hips burrowed in tunnels along the shores of Utah.

This dinosaur, Fona herzogae, roamed these shores at a time when Utah closely resembled the Florida Everglades. During the mid- to late-Cretaceous period, the Western Interior Seaway divided North America.

Now, below the desert that has taken its place lies a rich collection of fauna, waiting to be uncovered.

How was Fona discovered?

Haviv Avrahami, who has been studying Fona for the last decade and formally named the dinosaur recently, said discovering these dinosaurs required knowledge of two fields — geology and biology. This provides paleontologists with an understanding of which rocks preserve fossils and of the animals preserved within them.

Avrahami is a Ph.D student at N.C. State University and digital technician for the “Dueling Dinosaurs” exhibit at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences.

“What we knew early on,” he said, “is that a particular rock unit in Utah holds particularly interesting vertebrate fossils.”

Exploring the area of Utah where these rocks are prevalent, Avrahami’s team discovered a rock outcrop with some bones pointing out of it. They chased those bones until they found the source. He told The News & Observer that if these bones were buried directly in “solid, solid bedrock, it’s a pretty good chance then that we found a new dinosaur site.”

“We got really lucky that when we dug in, there were multiple complete specimens, possibly an entire family of Fona, just in these tight little bundles under the earth that are probably burrows.”

The team discovered six or seven individuals at five locations in Utah. Avrahami said his team has been discovering new locations faster than they can excavate them.

Burrowing into history

It is unusual for dinosaurs to be found as complete specimens. Luckily for the researchers, since these animals basically buried themselves, “the preservation quality is absolutely exquisite,” said Avrahami.

He said many animals in the same region from the same period in time lived above ground. This meant their bones likely flowed away with the river, making it more difficult for researchers to piece their stories together.

The fact that Fona can be found as complete specimens is a big clue that the species is a burrowing one. Actually studying these complete specimens allowed researchers to confirm this.

Avrahami noted that Fona had “really strong arms that would have helped it to scrape away the dirt from the tunnels as it was digging.” At the same time, Fona had “really strong hips and strong legs that would have stabilized it.” Its freakishly large feet provided Fona with the ability to “kick bucket loads of dirt from out of its home.”

A name that honors the future and the past

“People oftentimes have this assumption that when paleontologists find a new dinosaur in the field, we give it a name the next day,” said Avrahami.

In reality, he said, the process can take five to 10 years. In order to name the dinosaur, he said, “I traveled across the United States and across the world.” The team had to study all of Fona’s bones, comparing them to similar dinosaurs to ensure that Fona’s structures are unique.

The culmination of this process: Avrahami and his team created a special name for the species — Fona herzogae.

The genus, Fona, was chosen in honor of Fo’na — an ancestral legend of the Chamorros from the Island of Guam in the Marianas. “That’s where my ancestral roots are from,” Avrahami told The News & Observer. “So I wanted to honor the ancient culture and our ancestors by choosing that name.”

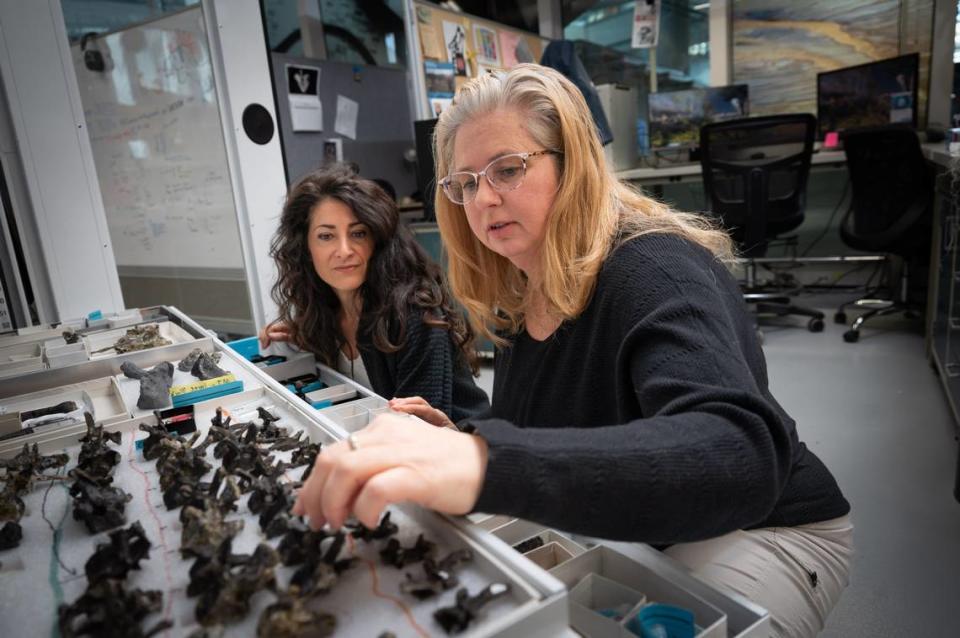

The species name, herzogae, honors Lisa Herzog, the paleontology operations manager at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences. Avrahami said Herzog showed him the ropes when he started working at the museum a decade ago. “She’s been just an absolutely critical component to the success of our entire paleontology program.”

What now?

Avrahami hopes to find out more about how Fona interacted with other dinosaurs and analyze its skull by creating detailed 3D-visualizations of the structure using an iPhone.

He also wants to find out more about how all “small bodied, early diverging ornithischians” — he calls them SPEEDOS — relate to each other to develop a family tree. This group includes Fona.

“Imagine if you went to a family reunion of SPEEDOS, you know, it’d be like walking in, and everybody has amnesia, and now you’re the forensics detective that needs to figure out how everybody is related to each other. And that’s kind of what my job is right now.”

He said family trees form the pillar of paleontology, providing information about how dinosaur features evolved in response to dramatic changes like the increasing global temperatures and rising sea levels that occurred during the Cretaceous period. These are changes mirrored by the modern world today.

That’s why paleontology is so important, Avrahami said.

“The world we live in now is only a single snapshot of the history of life on planet Earth. But paleontology adds the video frames to that story. That helps us fill in the gaps between our understanding of how life got to the way it is now.”