In sunny Arizona, a relocated gas plant ignites questions over who profits and who pays

MOHAVE VALLEY – At the corner of King Street and Aquarius Drive, on a dilapidated structure used for farmworker housing, a piece of a particle-board sign patches up a hole in one window where an air conditioning unit likely used to be. What’s left spells out the words “Energy Efficient.”

This building nestled among dusty alfalfa fields is now the closest residence to the new proposed location for the Mohave Energy Park, Mohave Electric Cooperative’s natural gas peaker plant project that has been fueling unrest across Arizona’s Mohave County since the beginning of the year.

Last December, senior residents of the Sunrise Hills neighborhood in nearby Fort Mohave found out about plans by local electricity distributor MEC and its regional provider AEPCO, the Arizona Electric Power Cooperative, to construct two quick-start turbines half a mile from their homes. The retirees spoke out against what they saw as deceitful skirting of zoning and notification procedures that left them mistrustful of the utilities’ intentions.

MEC vowed to search for another location. But on March 18, the cooperative’s CEO, Tyler Carlson, told the Mohave County Board of Supervisors they had been unable to find a suitable alternative site for the peaker plant, which the utility partners say is essential to maintaining energy reliability as this rural desert region south of Las Vegas continues to grow.

Weeks later, after coverage of the dispute by The Arizona Republic following months of interviews and inquiries, MEC pivoted and announced on April 12 to an invite-only group of member ratepayers and elected leaders that they had shifted plans for the natural gas facility to a site a few miles away.

Read the full first chapter here: A solar ban, a gas power plant and the rural retirees firing back at dirty energy

Now, people living near the new proposed location — a lower-income agricultural area close to tribal lands and several schools — are echoing Sunrise Hills residents’ concerns about how the peaker plant may endanger human and environmental health, but fear they’re up against an energy Goliath with renewed determination.

The utilities' unwavering push for a new gas facility despite local opposition and viable clean energy alternatives is also raising questions about potential hidden profit motives for individuals aligned with these not-for-profit cooperatives.

New location, same impacts

On a sun-drenched afternoon in early May, Kim Qualey walks hand-in-hand with her 7-year-old granddaughter Scarlet, half a block down the dirt road and across Aquarius Drive from their Mohave Valley home.

She points northeast to the patch of farmland less than a mile away where MEC and AEPCO now want to site two natural gas turbines with a 98 megawatt generating capacity – or maybe four turbines with a 196 MW capacity, according to updates to the project brochure since the utility quietly opted to relocate and expand the power plant.

Qualey has a certificate in agricultural science and has raised chickens and pigs at the family homestead since she and her husband, Sean, a former director of operations at the local high school, moved on Dec. 27, 1990, into the property they call their Christmas present to themselves. She said she understands the need for energy reliability and she’s not necessarily against the use of natural gas. But she doesn’t see why it needs to be so close to homes and schools.

“There’s 7-plus miles of desert behind that are unoccupied, and there’s a substation on Polaris and Willow,” Qualey said. “Couldn’t they move it back a little farther to protect people and animals?”

If MEC insists on solving its stated 30 MW electricity shortage at the site near her home, Qualey would prefer solar panels for neighbors. Though the utility has promised to use upgraded air filtration and more efficient engines, experts say peaker plants are still one of the dirtiest ways to produce electricity after coal and diesel. The resulting carbon dioxide emissions and common methane leaks also worsen climate change.

Standing in her yard on that bright 94-degree day, Qualey said she worries about how air pollution from the peaker plant might affect Scarlet and her 11-year-old brother, Zane, as well as all the children attending Mohave Valley Junior High and River Valley High School, both within about 3 miles of the new project site. Children are known to be at greater risk of health complications from breathing fossil fuel emissions. They’ll also be the ones saddled with future climate warming consequences.

“There’s always kids around, people have their grandchildren here in the neighborhood all the time,” she said while Zane, disguised as a desert bandit with a bandana over the lower half of his face, snuck up behind her with a loaded squirt gun.

“(MEC and AEPCO) could engineer a beautiful future that we all could live in amicably and be a leader in innovative technology to help save the planet,” she said, dodging Zane’s aim with practiced calm. “They could do the right thing. They know the consequences to the environment and the members they serve by building a peaker plant that close by.”

Member-funded ‘scare tactics’

In America’s sunniest state, these utilities are quick to dispute the idea that they’re anti-solar.

MEC’s commercial solar fields in Mohave County currently make up about 14% of its energy portfolio. AEPCO received board approval last October to install a large solar-plus-storage project near its coal plant at the opposite corner of the state that will get them closer to their goal of a 30% solar energy mix by 2026. The cooperatives are also applying for an array of federal grants to help fund more batteries and renewables.

But they have simultaneously pushed hard to gain public acceptance for this fossil fuel facility in Mohave County, sponsoring local newspaper ads and billboards claiming that “Natural gas power generation supports hospitals” and “Natural gas power generation supports cooling centers,” a summer necessity in this hot desert environment.

The not-for-profit, member-owned utilities declined requests from The Republic for records of how much ratepayer money they have spent on this advertising. Instead, Patrick Ledger, CEO of AEPCO, responded that “when we are developing special projects, the communication budgets may be higher in order to properly inform the public.”

Many residents and experts view the billboards as not only a waste of co-op members’ money, but as dangerously misleading. By definition, peaker plants are designed to fire up to meet surges in electricity demand during peak hours, not to power essential services.

“The hospitals have all been here for many, many years now and they all have backup generators. That is the truth,” said Kris Schoppers, a local real estate agent who opposes the project and has been working with Qualey to organize with Mohave Valley neighbors. “They're using scare tactics to make us think this is for our local benefit.”

In emails with The Republic, Allison Ellingson, MEC’s Chief Communications Officer, defended the advertisements, saying hospitals would prefer to rely on electricity from the peaker plant than from their diesel generators during a major outage. But Ledger told The Republic in February that the peaker plant would not have helped much with past outages in MEC's service area, most of which have been caused by faulty or damaged transmission infrastructure, not insufficient energy supply.

The answers underscore Schoppers' questions about who the construction of this gas plant would really serve.

Politics casts a shadow over solar

Similar pro-gas, anti-solar sentiments in the region date back to at least October of last year, when Mohave County Supervisors, all Republican, voted to ban new renewable energy projects on privately owned land until a better process could be worked out for managing impacts.

Email records obtained by The Republic reveal that MEC employees weighed in with elected officials on the wording of the moratorium before it was passed to ensure it wouldn’t derail their own renewable energy projects. Ledger has pointed to this exception for local utilities to make the point that the solar ban, which expired in early June and was replaced with more stringent zoning restrictions on renewables projects, “has nothing to do with our (gas) project.”

But Supervisor Jean Bishop told The Republic in late April she thinks the existence of the solar moratorium has facilitated both the formal approval and the public acceptance of fossil fuel energy generation in the region, potentially quelling more widespread resident opposition.

That’s no accident, according to Autumn Johnson, executive director of the Arizona Solar Energy Industries Association. She thinks elected officials stoke fear about excessive development in this rural-by-choice community to win votes.

“If anything, the locals are worked up about it because their policymakers have gotten them worked up about it,” Johnson said. “I don’t know what percentage of (solar) projects are going into Mohave versus other counties, but I certainly don’t think they’re being inundated. Most of the concern and fear is just based on misinformation, not based on what is actually happening with solar or wind development.”

Solar panels are indeed harder to spot in recent aerial images of Mohave County than the turbines and settling ponds of natural gas facilities. And the projects keep coming. By the Sierra Club's count, at least 36 new natural gas turbines are progressing through the state permitting pipeline, slashing at environmental regulations as they go.

Unisource Energy, the other major utility serving Mohave County, has a 200 MW natural gas expansion project that the company recently used to successfully lobby state regulators to ease rules around environmental assessments for gas turbines. The site for that project is farther into the desert away from homes than MEC's, close to a prison, one small solar field and the 653.8 MW Griffith Energy plant, which pulls its fuel from El Paso Natural Gas through the Transwestern Gas Pipeline and sells the electricity to Nevada Power.

In response to questions from The Republic about local energy development, Supervisor Travis Lingenfelter expressed support for gas projects in the name of “a strong Mohave County.” He views the solar moratorium as an important counterbalance to efforts by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to site more solar projects throughout the West to meet clean energy goals. He said Arizona’s renewable energy standards, which were eliminated in 2022, have cost residents money on their energy bills.

“Arizona will now let the invisible hand of the free market decide how electricity is produced towards saving Arizonans money on their utility bills,” Lingenfelter wrote in an email. (Electricity in Arizona is cheaper than the national average, according to recent reports from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.)

Supervisors Hildy Angius and Buster Johnson did not respond to emailed inquiries about the moratorium or these gas projects. Residents who spoke with The Republic have long suspected Angius of being overly sympathetic to MEC’s interests given public interactions they view as excessively friendly. She has not filed campaign finance disclosure forms with the county since 2017, so there is little evidence of incentives.

But email records obtained by The Republic reveal that a letter purportedly from Angius to state utility regulators in support of AEPCO's gas project was written and sent to her by Carlson, MEC’s CEO. Her emails also show her exchanging complaints about resident opposition to the peaker plant with MEC’s COO, Jon Martell. Reacting to Sunrise Hills neighborhood organizer Mac McKeever’s requests for information, Martell told Angius “I feel like he is setting us both up.” She replied minutes later that the situation was “too political” and she was “getting pissed off.”

All five supervisor seats are on the ballot in November, with Angius vacating in favor of a state Senate run. But it seems unlikely the county’s stance on solar will shift. One notable contender for Johnson’s spot is Mohave County’s current term-limited State Sen. Sonny Borrelli.

Borrelli introduced legislation in 2024 to let counties impose a 12.5% tax on solar generation, which failed after overwhelming opposition from statewide climate and public health groups.

His county supervisor campaign will carry over more than $76,000 in campaign contributions made during his state senate run, including from natural gas provider Southwest Gas and political action committees representing Arizona’s primarily gas-based electricity providers, including UNS Energy Corporation, PNW PAC and AzACRE, which is affiliated with AEPCO.

As a local representative, Borrelli may find his ideas more likely to gain traction. Emails to supervisors reviewed by The Republic included a half dozen from residents expressing support for the peaker plant based on the local energy generation and lower costs MEC and AEPCO have promised. And when The Republic connected with Danielle Ohle-Keck, a resident who started a petition last fall in support of the solar moratorium, she shared views that the economic benefits of solar projects are not enough to offset their disruption to open desert landscapes.

A report prepared for Johnson’s organization, AriSEA, estimated an example solar project would generate $30.9 million in tax revenue for Mohave County over its lifetime. Mohave County Economic Development Director Tami Ursenbach declined to provide The Republic with real numbers, but echoed the perspective of many of her elected officials and neighbors when she replied that completed solar projects offer little to the community in terms of taxes, jobs or energy reliability, since much of the electricity is exported for use out of state.

'2008’s answer to the energy problem'

To clean energy advocates, the fact that electricity generated by solar panels gets sucked out of sunny Mohave County via the region’s veiny tangle of transmission lines connecting Los Angeles, Las Vegas and beyond is evidence not of a need for local generation, but that northwest Arizona is incredibly well-positioned to tap into the grid for its future energy needs.

“It doesn't matter where the plant is because this goes on a grid,” said Amanda Ormond, a professor at Arizona State University and an expert on the regional transition to post-coal-dependent economies with three decades of experience working in Western energy and public policy.

“I think it's more that this is what makes utilities feel comfortable, to have a peaking plant. It's the old hammer they know," Ormond said. "They can turn it on when they need it. The world of wind, solar and battery takes a lot more active management.”

Ledger responded to The Republic’s initial story on the peaker plant project by underscoring that, as not-for-profits, AEPCO and MEC work solely for the benefit of their co-op members and that building a natural gas facility now is an essential bridge to the overall clean energy transition.

“As our (Integrated Resource Plan) demonstrates, and as every other utility in the region has similarly concluded, combining solar and battery storage with small efficient emission-controlled dispatchable peaker facilities is the lowest cost, most reliable, and most responsible option available,” he wrote.

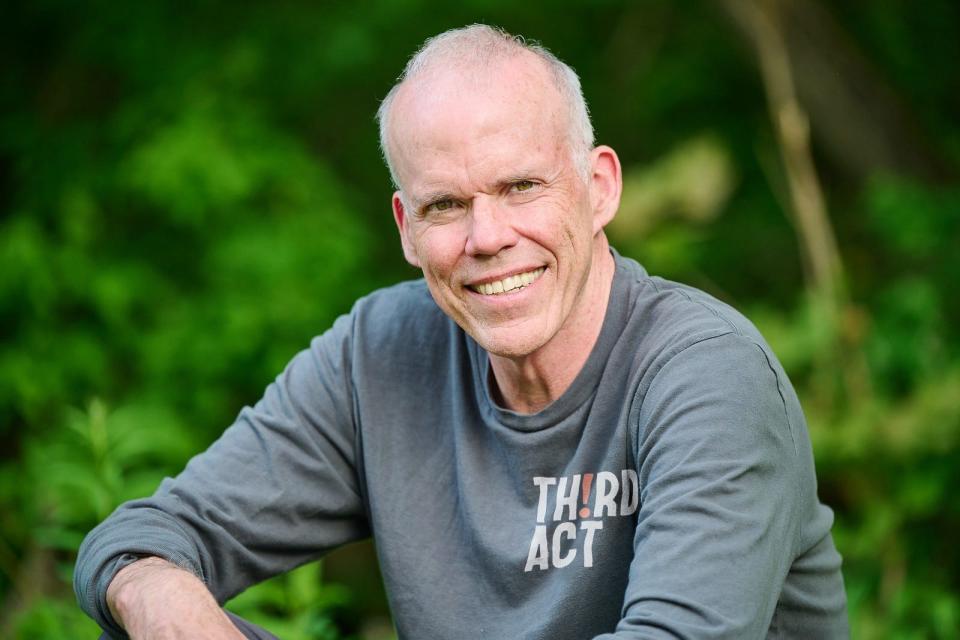

But environmentalists don’t see it that way. Bill McKibben, a well-known climate activist and environmental author, told The Republic the idea that building another fossil fuel facility in 2024 is in anyone’s best interests is absurd, especially given the trend of renewables becoming cheaper and more reliable every year while natural gas prices are notoriously volatile in response to international conflict. He views MEC’s 14% renewable energy generation (and Unisource’s 17%) in one of the country’s sunniest spots as a huge missed opportunity.

“Truthfully, utilities have a pretty good track record for being lazy thinkers about these things,” McKibben said. “A gas-fired power plant is 2008’s answer to the energy problem. If you build one now, you’re an absolute sucker because you’re putting yesterday’s technology in place for the next 40 years and it’s hard to imagine a bigger waste of money or a bigger way to contribute to the climate crisis that is liable to render Arizona uninhabitable.”

Energy experts assembled for a recent panel hosted by Canary Media came to a similar conclusion, calling nationwide efforts to build new gas peaker plants a “knee jerk reaction” by utility CEOs sticking to the old energy playbook. As data centers and other electricity-intensive industries are welcomed into communities based on projected economic benefits — a major factor metro Phoenix, which was recently ranked fifth globally on data center development — meeting skyrocketing energy demand with fossil fuel generation is incompatible with long-term benefits to consumers and with U.S. commitments to power sector emissions reductions, the experts said.

“I think it’s a tough job right now to be a utility load forecaster or planner because it’s such a critical moment,” said Maggie Shober, a research director at Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. “But it’s so important that we get it right, right now.”

AEPCO has emphasized that the electricity from its Mohave peaker plant will benefit the environment by facilitating the closure of its coal unit. Given the long queue of proposed renewable energy projects waiting to connect to nationwide grid infrastructure not fully ready for this shift, it’s a reality that there are obstacles to moving immediately into renewables.

But some Arizona-based clean energy experts would prefer to see existing coal plants stay active slightly longer while those details get worked out — which energy companies are being paid to do in other parts of the country — than support investments in new fossil fuel facilities.

“I would say, for my money, I'd rather have that coal plant temporarily running for three months out of the year than to go build that new gas plant,” Ormond said. “Power outages during storms in Texas showed us that natural gas is not as reliable as they want to believe, or as clean, especially when you don’t count upstream methane emissions. It’s just the good ‘ole boy network saying, ‘This is the way we do things.’”

Ormond would urge MEC to pursue more aggressive energy efficiency options to balance increasing demand.

In response to questions about the utility’s efficiency efforts, Allison Ellingson, MEC’s communications officer, told The Republic they’ve had good member participation on offers for home energy audits, weatherization, more tree shade and rebates for items like LED light bulbs, heat pumps and rooftop solar panels.

But MEC has seen little member interest in “smart thermostat” programs to reduce demand during peak times and has had to abandon other efficiency initiatives due to lack of staff, funding or approval by the state regulatory body, she said.

Ellingson represented MEC and the Mohave Energy Park project at two recent community meetings in Mohave Valley, on May 3 and June 4. At both, she stressed that Mohave County needs this peaker plant to ensure the utility can generate the additional 30 MW necessary to meet the community’s projected energy demands and support essential services. She also echoed Ledger’s points that solar panels are unreliable on cloudy days.

But documents accessed by The Republic show that MEC and AEPCO jointly submitted an application to the Arizona Corporation Commission on April 17 for approval of an electric energy services agreement with Nucor Steel in Kingman, a local steel manufacturer seeking to expand its operations and energy use.

In it, the utilities propose to develop a 50 MW battery storage system and future solar project to “serve the expected Nucor peak load,” all of which raises the question of why the same approach can’t serve the expected peak load of Mohave County residents.

'No profit motive'

So why build a gas-fired peaker plant that nearby residents oppose given costly risks to a livable environment and increasingly promising energy alternatives?

After The Republic published the first story chronicling local opposition and expert perspectives on the project, Ledger sent the reporter an email:

“We really are a totally different organization than most of the big utilities — no profit motive, democratic, member-owned, community based — so the usual script about us being motivated by profit and what’s good for us vs. what’s good for the consumer really doesn’t cut it,” he wrote.

Ledger also called ASU law professor Troy Rule, who was quoted in that first story casting doubt on the benefits of peaker plants, and offered to “help clarify some of his misunderstandings.” Rule is an expert on solar energy markets and author of the books “Solar, Wind and Land: Conflicts in Renewable Energy Development” and “Renewable Energy: Law, Policy and Practice.” He has followed what he calls a recent nationwide disinformation trend undermining renewable energy projects.

“We are a not-for-profit cooperative, so we have no profit motive,” Ledger wrote in his email to The Republic. “Had you or Professor Rule conducted appropriate research, you would have discovered that we do not have shareholders, we have no connections to the fossil fuel industry, and in fact that we serve lower-income rural communities.”

Rule declined the offer from Ledger, but followed up with The Republic to clarify that he thinks the push for this peaker plant likely is profit motivated, and not in service of lower-income rural communities.

“There’s a lot of transmission infrastructure relatively close to their site, which means they can ship this power throughout the Southwest at peak times and sell it for a lot of money,” Rule said. “And that’s an attractive thing for them because they have significant debts and stranded cost problems and are looking for a way to improve their financial situation.”

Sandy Bahr, who directs the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter, agrees.

“These things are not cheap so once they invest in building these turbines they’re going to want to run them and keep running them,” Bahr said. “And if we move away from fossil fuels faster than they expect, they could end up with significant stranded assets.”

In a February interview with The Republic, Ledger mentioned the anticipated closure of AEPCO’s coal plant, the Apache Generating Station, as a reason they needed to bring this gas plant online before the Biden administration’s new rules about carbon emissions from fossil fuel plants take effect.

To Ormond, the expert on transitioning away from coal, that argument doesn’t add up either.

“We’re at this really interesting period when the economics have completely changed,” she said. “Solar combined with battery storage is the lowest cost resource available. But change is difficult and systems are getting more complex. Smaller, rural co-op utilities are typically slower to adopt newer technologies. Utilities are projecting huge load growth in the West, creating resource adequacy problems. If you can build a peaker plant in Arizona, you can turn it on, sell excess energy and make some really good money.”

That “really good money” is not officially counted as profit, since MEC reports $0 in net income most years. But the utility’s accounting on executive salaries raises questions.

Tax filings reviewed by The Republic reveal that Carlson, MEC’s CEO, was paid $1.35 million by the utility in 2022, with an additional $267,535 in “other” compensation. That’s more than the $1.2 million that SRP, Arizona’s much larger, urban utility company, paid its CEO.

Ledger explained it’s not unusual for rural utilities to offer higher salaries to recruit the necessary talent to manage the dynamic challenges of providing electricity to far-flung consumers. At other times, he said employees of utility cooperatives accept lower salaries because they believe in the work. Tax filings show Ledger was paid $740,947 by AEPCO, also a rural electric cooperative, in 2022, with an additional $90,760 in “other” compensation.

What is unusual and hard to explain, according to not-for-profits expert Robert Ashcraft, who directs ASU’s Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation, is the dramatic fluctuation of Carlson’s salary year to year, which bounces from $1.66 million in 2017 down to $617,483 in 2018, back up to $1.24 million in 2020 and then down to $658,030 in 2021, before doubling again in 2022.

Read more from this reporter: The latest on climate from Joan Meiners at azcentral

The fact that MEC zeroes out its net income on tax filings each year, matching large revenue numbers with expense numbers, is also odd. In 2022, for example, MEC reported revenue and expenses to exactly match at $96,009,131. Ashcraft said this begs the question of where the surplus revenue is spent in order to even out the financials each year.

“That salary fluctuation rollercoaster is quite fascinating,” Ashcraft said. “You normally don’t see that in nonprofits. You might see it in for-profit shareholding companies, depending upon CEO performance contract details.”

Carlson also received between $27,000 and $42,000 annually for his participation on AEPCO’s board during those years, while his additional “other” compensation at MEC was listed at between $115,009 and $267,535.

Neither Carlson nor Joe Anderson, who oversees executive salary changes as the president of MEC's board, responded to The Republic’s requests for an explanation of how Carlson’s compensation is determined or for copies of meeting minutes when those decisions were made.

Over the phone, Ledger explained that “other” compensation packages, which include items like retirement benefits, company cars and annual bonuses, sometimes reflect performance on project goals, “if I do well.” After a good year, the utility might also issue checks to some of their partners. AEPCO reported a net income of $3.15 million in 2022 and $9.65 million in 2021.

Ledger estimated his own performance bonus last year at less than $40,000, then called The Republic’s line of questioning “grotesque” before abruptly ending the call. Later via email, he clarified that “No employee of Arizona Electric Power receives any direct or special pecuniary gain from the development of new resources. We have a “smart goal” program that provides small incentives for performance linked to our strategic plans and goals.”

But to not-for-profit experts, this closed-door practice suggests the potential for individual profit motives for executives who successfully push through profitable projects.

“When you think nonprofit, it’s really a tax status,” Ashcraft said. “There are so many types of nonprofits and not all are charities. Some of them are billion dollar enterprises. It doesn’t speak to purpose, mission, results, all the rest, which can have bearing on CEO compensation packages.”

An energized community, divided

Questions about profit motives came to a head in Mohave Valley at a community meeting about the peaker plant in early May.

Out of more than 70 attendees, almost everyone who spoke opposed the project, including several enrolled members of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, which had not yet publicly taken a stance on the project.

“We’re just the Indian people, half of you don’t even know we’re here,” said Beatrice Jacobo, a tribal member speaking as an individual at the meeting. “But we’re all in this together and I’m going to stand up and fight.”

The project site is less than 800 feet from tribal land. Ashley Hemmers, the tribal administrator responsible for management of public services on the reservation, later told The Republic the land is one of vanishingly few options where the tribe may want to build future homesteads. She spoke against the project on behalf of the tribe at a Mohave County Board of Supervisors meeting a few days after the community gathering.

As of early May, five months into AEPCO's public push for the project, Hemmers said she was not aware of any attempts by either utility to consult with the tribe on environmental or community impacts of the project. MEC’s Ellingson said the utility sent an email to tribal chairman Tim Williams but never got a response. Hemmers responded by saying she thinks MEC is putting out a lot of misinformation. AEPCO has since restated its intention to consult with the tribe, but Hemmers remains wary.

“They put billboards up because they think they can just buy land and tell us what to think and we’ll put up with it,” she said.

The only person not employed by MEC to speak in support of the project at the community gathering in May was Ted Martin, the Mohave Valley Fire Department chief. Martin stood at the front of the room for much of the meeting, offering impassioned counterpoints in support of the project to other speakers' concerns.

His behavior rubbed some attendees the wrong way. Hemmers told The Republic Mohave Valley has struggled with funding, recruiting and maintaining firefighters in recent years. To help ensure fire services are available, the tribe has contributed funds. Now she feels Martin should be respecting their position on the project.

When The Republic connected with Martin, he called his neighbors' suspicions about his motives “sickening” and said he supports the project because he believes it to be in the best interests of the community, especially lower-income residents who would struggle if electricity prices went up. He feels that misunderstandings of the risks have drummed up emotional responses.

But Pastor Roy Hagemyer, who ministers at the nondenominational Way Christian Church in Fort Mohave, isn’t buying it. He lives about a mile from the proposed site for the plant in Mohave Valley.

“Nobody, as a private citizen, wants a peaker plant in their backyard if there isn't something in it for them," Hagemyer told The Republic, adding that Martin seemed "far too zealous."

Along with community organizer Kris Schoppers, Hagemyer also has questions about Chip Sherrill’s personal interests in the project. Sherrill is a prominent local farmer, land and business owner and the current chairman of the Mohave Valley Irrigation and Drainage District. Hagemyer said Sherrill was in the room at MEC's invite-only meeting announcing the new project site in Mohave Valley on April 12.

On its website, the district says it “has the right to subcontract its entitlement to entities and individuals” within its management area. It determines which farmers, subdivisions and facilities get access to water. In an agricultural community with restricted pumping and fallowed farm fields due to lack of water, the idea that a commercial project might be cutting in line is quick to raise hackles.

In February, Ledger told The Republic he was not yet sure where the peaker plant would get the water it needs to run, which he estimates at around 9 million gallons per turbine per year, for a potential annual total of 36 million gallons if four turbines are eventually installed. He noted this is less than would be used for farming at the site and that they will comply with water quality standards set by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality.

After the site relocation to Mohave Valley, Ledger said in May that AEPCO is working to purchase and rezone the land, and that the sale will include water rights. The utility has submitted its rezoning request to the county but did not respond to recent requests for updates on the land sale.

ADEQ told The Republic in late June that the agency had not received any applications for the required air or water quality permits related to this project. Since the site is in a rural area without water restrictions for industrial facilities, Bahr of the Sierra Club said she isn't holding out hope the eventual permits would "include anything strong," meaning the peaker plant could potentially run continuously without concern about air pollution or water use limits.

As far as Sherrill's potential control over water the project still lacks, The Republic found documents that confirm his ownership of land near the new project site and others that show the transfer of a portion of water rights in 2014 between Sherrill’s company and a Delaware-based LLC named WPI-919 AZ Farms, which is the current owner of the land parcel proposed for the gas facility. On different pages of that transfer agreement, Sherrill signed as both the General Partner of Sherrill Ventures, LLLP and as the Chairman of the Mohave Valley Irrigation District.

WPI-919 Farm AZ, owned by New York City-based water asset manager Marc Robert, was previously accused by a CNN investigation of buying up land in the West so as to hoard water rights in a practice known as “drought profiteering.” It’s not illegal, but is viewed by many as an unfair foreign power grab as the West teeters ever closer to the “water wars.”

Sherrill did not directly respond to requests for details on his interest in the peaker plant or influence over its water access. His secretary, Kerri Hatz, told The Republic Sherrill is not currently involved with any projects with MEC.

Speculating on water and quality of life

On a sunny Saturday morning in May following the community meeting in Mohave Valley, Robert Jacobo loads his yellow lab, Bo, into his red Jeep Grand Cherokee and bumps down a sandy road to the banks of the Colorado River where it separates Arizona from California. He scopes out a few spots before parking and unloading his fishing gear.

Jacobo, an enrolled member of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe who is the son of Beatrice Jacobo and cousin to Ashley Hemmers, was born and raised in this area and feels a deep connection to the river and the landscapes viewable from its best fishing spots. Getting out on the water reminds him of his dad, who passed away two years ago.

“Culturally, fishing is a big thing,” Jacobo says as he works a worm onto his hook. “If you talk to tribal elders, they’ll tell you stories about when the river was five miles wide. I would think that’s a little exaggeration, but definitely, you look at the lands around here and you can tell, ‘oh this used to be underwater for sure.’ And then you realize, yeah, you’re a fisherman at heart.”

Jacobo has spoken out alongside his relatives at both community meetings about the power plant in Mohave Valley. He also wrote a recent opinion piece about being stewards of this land, which he views as incompatible with allowing a new gas plant to be built here.

He reels in a striped bass just as a family speeds by on their motor boat towing a raft with screaming kids in its wake. Bo is ecstatic.

Thirty miles upriver in Bullhead City, where MEC is headquartered, Mohave County residents used to celebrate their location along the Colorado River with an annual river festival. But in 2019, the event was canceled for being “too divisive.” The cracks caused by drought and water restrictions ripple far and wide throughout this community.

Recent water use limitations frustrate locals like Steve Arnold, who runs a hay distribution business and grows shrinking quantities of fruit for sale near the original site for the peaker plant in Fort Mohave. Arnold opposed that location for MEC’s Mohave Energy Park primarily because of uncertainty surrounding how much water the plant would use and where it would come from.

“MEC has done two solar plants, which I have no problem with,” Arnold told The Republic during a tour of his property. “They're fairly passive, there's no threat of explosions, they're not really unsightly and they don’t use water (after construction). But (natural gas) power plants, they have to pump water. It’s like, ‘Hey, let’s just forget about the farmers.’”

Four miles south from Arnold’s land, at the new proposed project location in Mohave Valley, Kim Qualey drives her ATV past fallowed farmlands and the farmworker housing with the “Energy Efficient” sign patching up a broken window. Given how agriculture has already been squeezed dry, she and her neighbors do not think a peaker plant is a reasonable use of the region’s “liquid gold,” or a reason to sully its clean air.

When she reaches the corner of the project site, Qualey pauses and looks out over rusty irrigation canals filled with sand that fan out through desiccated alfalfa fields like spokes of a forgotten wheel.

In the distance, the two towering natural gas turbines of Calpine’s South Point Energy Center, built at 530 MW with peaking capacity in 2001, pump electricity onto the grid for sale throughout the tri-state area.

This report was made possible in part by a grant from the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Joan Meiners is the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com. Read more of her coverage at environment.azcentral.com.

Sign up for AZ Climate, The Republic's weekly climate and environment newsletter.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Profit motives and political influence plague Mohave gas plant project