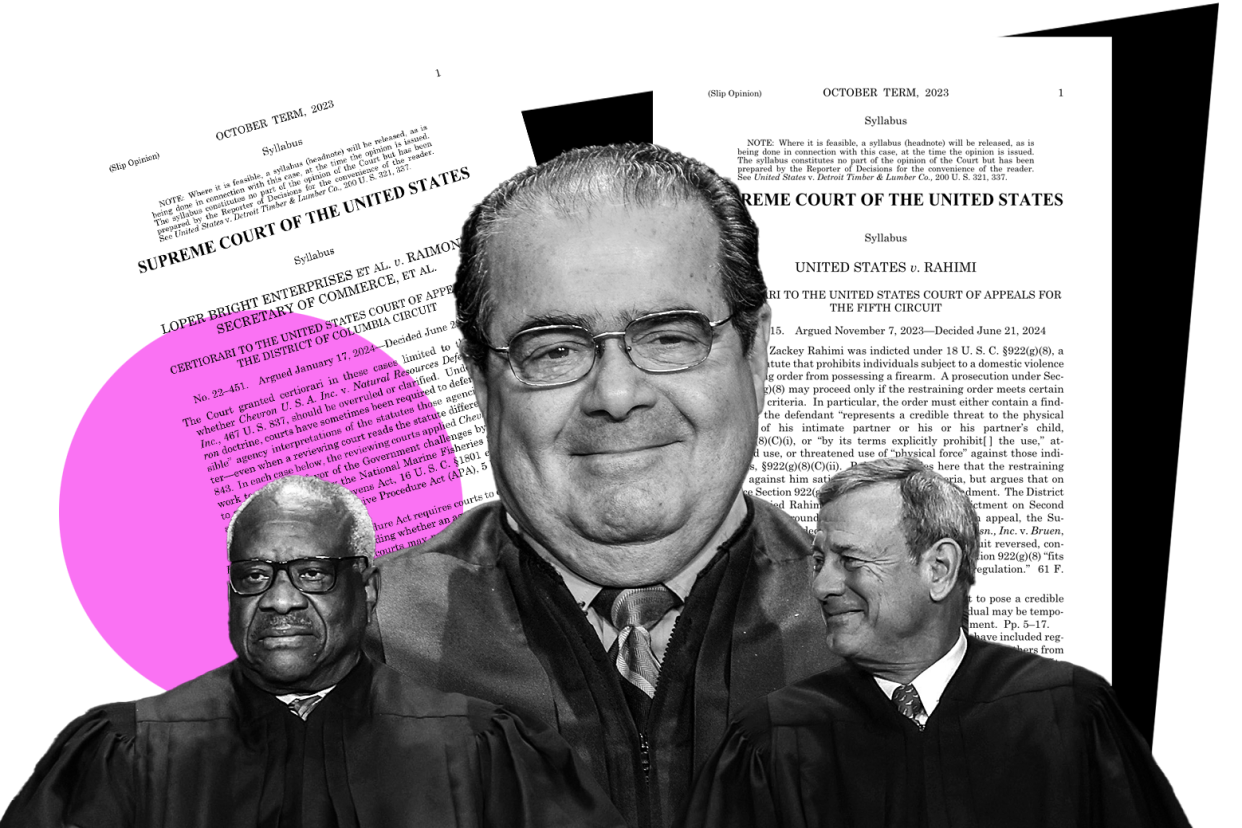

This Supreme Court Has Betrayed Antonin Scalia’s Legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the wake of Friday’s decision by the Supreme Court in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, commentators will have a field day picking apart the case’s implications for separation of powers, the future of the regulatory state, and the upheaval of administrative law professors’ syllabi. I’m left, however, with a different immediate thought: about the late Justice Antonin Scalia, and the French proverb that every revolution devours its own children.

Scalia, more than anyone else, was the architect of the conservative counterrevolution that swept the federal bench during the Reagan era and reached its apotheosis in the 2022 Dobbs decision that overruled Roe v. Wade. For Scalia, a social conservative who railed against Roe every chance he got, a ruling like Dobbs was a consummation to be devoutly wished. But, strikingly, in many other areas of the law, the court’s current right-wing supermajority has moved far beyond, and in some cases torn down, the judicial goalposts that Scalia erected. Today’s conservative justices purport to celebrate the philosophies Scalia championed—textualism and originalism—but he might not even recognize them as they are now being practiced.

Start with Loper Bright. On the surface, the case concerned an obscure federal regulation requiring commercial fishing operations to pay for observers to board their vessels and monitor their compliance with conservation goals. Not content to challenge that regulation, the fishermen plaintiffs in Loper Bright cast their nets wider, hoping to deep-six a foundational principle of administrative law known as the Chevron doctrine. Chevron—decided 40 years ago, and one of the most frequently cited Supreme Court decisions of all time—declared that when an administrative agency exercises authority pursuant to an ambiguous federal law, the agency may interpret that law in any reasonable manner. The plaintiffs contended that Chevron violated the separation of powers by allowing agencies rather than the courts to say what the law is.

On Friday, the court agreed with the plaintiffs and overruled Chevron. It based its decision largely on a provision of the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act that calls upon courts to “decide all relevant questions of law” and “interpret … statutory provisions” when reviewing agencies’ handiwork. Yet that provision, like many in the vaguely worded APA, is question-begging: It doesn’t preclude judges from deferring to reasonable interpretations offered by agencies. Scalia recognized all of this decades ago, deriding as a “quite mistaken assumption” the notion that courts must construe regulatory statutes from scratch. Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion never wrestles with that point, or with Scalia’s other oft-repeated defenses of Chevron, dismissing him as an “early champion” of that decision who later saw the light.

The outcome in Loper Bright was unsurprising—conservative justices have been telegraphing their antipathy to Chevron for years, and the doctrine was already on its last legs. My own view is that the court was wrong to reject Chevron, because the specialists who staff agencies are better equipped than generalist judges to figure out how laws should apply in new and unforeseen circumstances. And if Congress thought the court had been mistaken for the past 40 years, it could always uproot Chevron by revising the APA. But, regardless of the merits of the case, Loper Bright signals how thoroughly the court’s right wing has turned its back on Scalia, its erstwhile avatar.

Scalia wasn’t on the court yet when Chevron was decided, but he soon became an unabashed superfan of the Chevron doctrine, defending it in public remarks as well as in majority and dissenting opinions. Depending on how cynical one wants to be, one can identify both principled and unprincipled justifications for Scalia’s Chevron fandom. The principled justification is that when Congress leaves a statutory silence, it would prefer to have that gap filled by agency decisionmakers who answer to a democratically accountable president, as Scalia insisted they must. Somewhat less principled was Scalia’s confession that Chevron rarely required him to accept results he personally abhorred. The son of a formalist literature professor, Scalia was what Harold Bloom might have called a “strong reader” (or misreader?) of statutory texts. That meant that he almost always found enough clarity in the underlying statute to happily ignore the agency’s interpretation of it, even under Chevron.

The most cynical explanation for Scalia’s cheerleading for Chevron is that, in the 1980s and early 1990s, judicial deference offered a convenient cover for Republican agency officials’ deregulatory interpretations of broadly written public interest statutes—as happened in the Chevron case itself. The flipside of that explanation may also underlie the current majority’s hostility to Chevron: during the Clinton, Obama, and Biden administrations, the doctrine of deference has made it harder for business-friendly judges to dismantle agency rules that protect workers, consumers, and the environment. Indeed, as the chief justice’s Loper Bright opinion notes, even Scalia himself appeared to sour on Chevron in the last year or so of his life. Abandoning deference, one might argue, proved a small price to pay for the deconstruction of the administrative state.

But it isn’t only Chevron that marks the divide between Scalia and his conservative acolytes. In 1990, Scalia wrote the seminal decision in Employment Division v. Smith, holding that the First Amendment’s free exercise clause doesn’t give religious practitioners a license to ignore neutral, generally applicable laws. To be clear, Smith was unpopular from the start, including among liberals; lopsided majorities in both houses of Congress attempted to overturn it within a few years. But the decision drew especially harsh scorn from religious conservatives. Indeed, the story goes that the feisty Scalia used to ask prospective law clerks to identify their least favorite decision of his so that he could spar with them—but told them not to bother naming Smith because everyone hated it. For my money, Smith got it right: As Scalia wrote, a system in which the government has to justify applying general laws to everyone threatens to become “a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself.” But recent decisions make clear that the current conservative supermajority, in their zeal to undermine antidiscrimination law and the separation of church and state, will soon part ways with Scalia and overrule Smith.

And consider Scalia’s most famous legacies: textualism and originalism. In the landmark Heller case from 2008, Scalia held that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to own firearms, unconnected to the amendment’s reference to militia service. I’m not here to defend Heller; Scalia almost certainly got the text and history wrong and, more fundamentally, neglected the need for law to respond to changing realities. But at least the Heller court signaled its acceptance of longstanding regulations barring guns from being carried by dangerous people or in sensitive places.

In its 2022 Bruen decision, however, the court blew past that reassurance and drove Second Amendment law to a precipice from which the jurisprudential foundations laid by Scalia were barely visible. According to Justice Clarence Thomas’ majority opinion, gun control measures are presumptively unconstitutional, and can be rescued only if the government can show a tradition of analogous restrictions from some unspecified era in the 18th or 19th century. This reasoning is reckless and unworkable—and has virtually nothing to do with Scalia’s brand of textualism or originalism. It’s no wonder that Scalia once remarked of Thomas’ style of judging, “I’m an originalist and a textualist, not a nut.” In last week’s Rahimi case, the court retreated to some extent from the heights of Bruen’s absurdity, but the chief justice’s incoherent majority opinion, and the spate of dueling concurrences, showed that the court misses Scalia’s steadying hand.

To cite one more example, early in his career Scalia recognized that public employees can be required to help fund the unions that, in turn, have a legal duty to represent them. Yet in the 2018 Janus decision, Justice Samuel Alito unceremoniously discarded this insight in the course of holding that so-called “fair share fees” violate the First Amendment. (A disclosure: as Illinois solicitor general, I represented the losing side in the Janus litigation.)

The point of all of this is emphatically not to retrospectively laud Scalia as a justice. His jurisprudence all too often relied on tendentious readings of history and rigid parsing of legal texts to prop up a stagnant and exclusionary constitutional order. The point, instead, is to show the extent to which Scalia’s conservative successors have broken free of the philosophical moorings established by his decisions.

It’s not unusual for zealots to compete with one another to be plus catholique que le pape. But the current court, in seeking to serve the partisan interests of the Republican Party by any means possible, has taken the law to places even the archconservative Scalia was too intellectually honest to go. Scalia, at least some of the time, stopped short of acting on his ideological preferences thanks to an overriding commitment to judicial restraint; today’s conservative justices rarely have such qualms. The doctrine of deference to administrative agencies is only the latest of Scalia’s edifices to topple. Perhaps the real lesson is that every revolution devours its own fathers.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)