The Supreme Court Is Out of Control. This Is Our Best Hope.

The Supreme Court ended this term with a bonanza of terrible, antidemocratic decisions. On Monday, the justices tossed aside the fundamental principle that no one is above the law, declaring that presidents have between presumptive and total immunity from prosecution for official acts. This decision may make it impossible to hold former President Donald Trump accountable for trying to overturn the 2020 election, and will embolden him to abuse his power even more flagrantly if he is elected again.

The court’s right-wing supermajority also decreed that courts can ignore federal agencies’ reasonable interpretations of the laws they’re charged with administering, substituting judges’ own views instead, and that businesses can challenge regulations years or decades after they went into effect. Together, these decisions will destabilize the government, leaving rules on everything from clean water and air to safe food and drugs and to climate change subject to second-guessing by judges.

All of this comes on top of the court’s many other decisions in recent years that have chipped away at our rights and undermined our democracy: allowing states to ban abortion, weakening public-sector unions, invalidating a student debt forgiveness plan, gutting the Voting Rights Act and flooding our politics with dark money, preventing Congress from expanding Medicaid nationwide, banning affirmative action in higher education, constricting the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to address climate change, and striking down gun safety laws.

It does not require a crystal ball to know that if nothing changes, the court will continue to take away the rights of workers and other non-powerful people, strike down progressive laws, and protect the interests of the wealthy, corporations, and the Republican Party. And even when Supreme Court decisions aren’t in the headlines, they chill Congress from even attempting to pass laws because of the risk that courts might strike them down, and limit what we can imagine for our future.

Right now, we have a Supreme Court that acts as a power-hungry, partisan policymaker. It is fundamentally antidemocratic for unelected judges to constantly overturn laws passed by the people’s elected representatives in Congress. But things do not have to be this way—Congress can reshape the court and change how it works.

As we argue in a new People’s Parity Project report called “Protecting Workers’ Rights and Democracy from the Courts: A Practical Guide to Court Reform,” court reform is an urgently needed solution to the many problems of the federal courts. It could correct the Supreme Court’s current far-right warp and shift the power to make policy and determine our future back to the people and their elected representatives. It could also address other related problems, including the justices’ unethical behavior and refusal to recuse themselves in the face of obvious conflicts of interest, the disconnect between election outcomes and the court’s membership, and the justices’ increasing habit of deciding vital questions through the “shadow docket” without explanation.

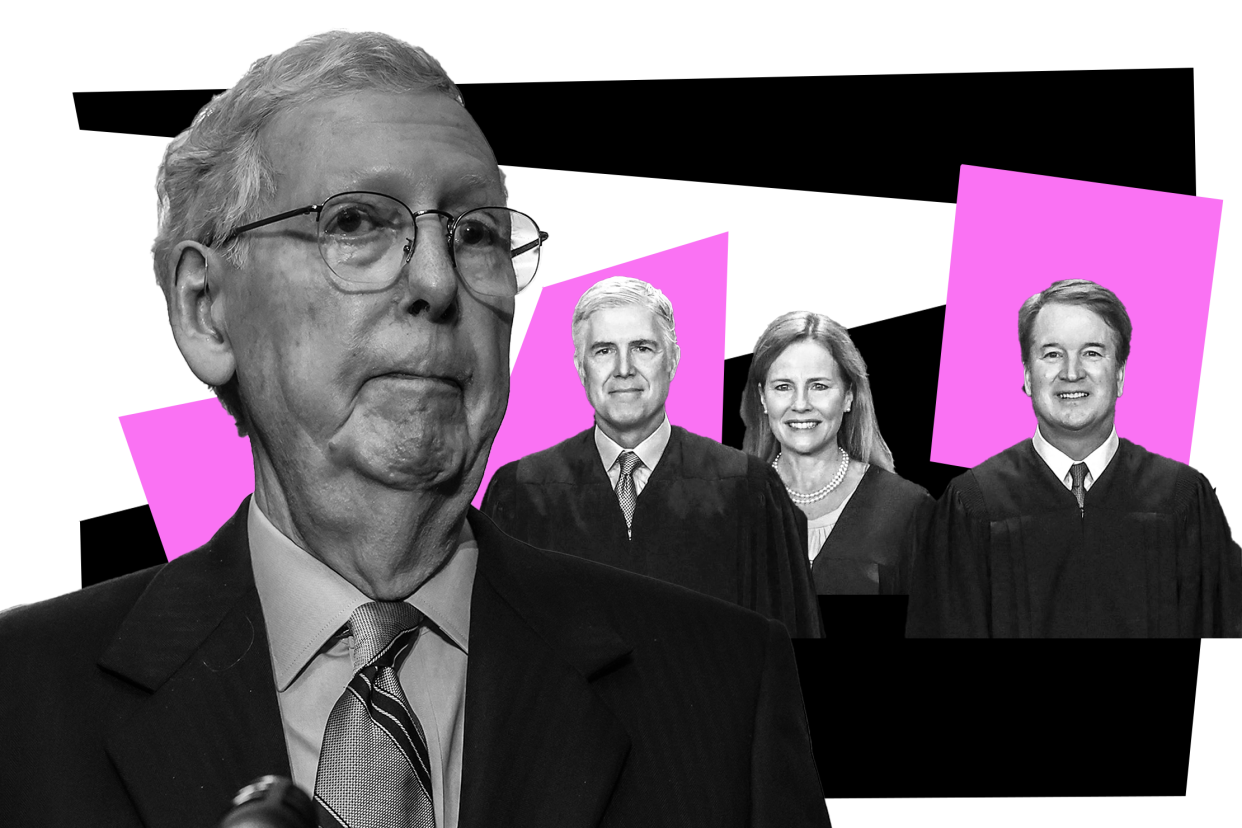

The current Supreme Court is unusually extreme in many ways. Its right-wing supermajority is the result of right-wing court packing, including Senate Republicans’ refusal to consider President Barack Obama’s nominee after Justice Antonin Scalia died in 2016, effectively shrinking the court for more than a year until they confirmed Neil Gorsuch in 2017; their confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 despite credible allegations of sexual assault against him; and their rushed confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett just a week before the end of the 2020 election.

That supermajority is also unusually antimajoritarian, in that three of its members were appointed by a president who lost the popular vote, and four were confirmed by senators who represented a minority of the population. And it is particularly brash in its willingness to issue decisions without explanation, disregard ethical norms, and overturn decades-old precedents and the decisions of democratically accountable officials to benefit the political party that nominated most of its members.

But the current court is not an aberration in terms of the antidemocratic role it plays. Throughout American history, the Supreme Court has struck down democracy- and equality-enhancing laws passed by Congress while leaving in place policies that benefit the wealthy and powerful. In the late 1800s and through the 1930s, the court backed employers and the government as they violently suppressed a burgeoning labor movement, upholding injunctions against strikes, imprisoning labor leaders, and invalidating hundreds of worker-protective laws. In perhaps its most infamous decision, Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), the court held that enslaved Black people were not citizens entitled to the protections of the Constitution—a decision that helped spark the Civil War.

During the Reconstruction period after the war, Congress amended the Constitution and passed numerous laws to safeguard the rights of formerly enslaved people. But the court quashed these attempts to guarantee equality and justice by interpreting the Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution narrowly, and striking down or narrowing many of those laws. This permitted decades of racist disenfranchisement, segregation, and racial terror against Black people. The court held that Congress could disregard treaties with Native American tribes, and upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Beginning in the 1970s, it invalidated campaign finance legislation. It handed the presidency to George W. Bush in 2000.

This long history of antidemocratic and unjust court decisions is sometimes overshadowed by the towering role in the public imagination occupied by progressive decisions like Brown v. Board of Education (1954), striking down school segregation, Roe v. Wade (1973), striking down state laws banning abortion, and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), striking down state laws banning gay marriage. But none of those decisions struck down laws passed by Congress; rather, they enforced a Reconstruction-era law Congress passed to allow courts to strike down unconstitutional state laws.

These famous decisions also generally followed the sweep of public opinion, rather than going against it. Congress has acted more often to protect minority rights than have the courts. And as the court’s recent reversal of Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health shows, relying on the courts to consistently protect minority rights is not a good bet.

Reforming the federal courts would increase democratic legitimacy. It could make it harder for unelected judges to strike down legislation passed by living voters’ elected representatives on the basis of judges’ interpretations of a Constitution that is very old, short, vague, and difficult to amend. Many court reform tools would shift the power to decide which policies the Constitution permits from courts to the public, social movements, and democratically accountable officials.

This shift would allow a more progressive vision of the Constitution to prevail. According to the current Supreme Court, the Constitution is a collection of rules that help corporations and property owners and keep existing hierarchies in place. But workers and their labor movement understand the Constitution differently—as requiring the expansion of democracy to the workplace, recognizing workers’ rights to livable wages and benefits, including historically excluded workers like farmworkers and gig workers, and necessitating a more democratic government. Court reform would allow this more democratic, egalitarian vision to carry the day, and would broaden the futures people can plausibly demand beyond the restrictive boundaries drawn by the federal courts.

Our report does not prescribe one perfect or best court reform strategy, because there is no one fix for all the problems of the federal courts. Instead, it explains a number of court reform tools, each of which could address some of the problems. These tools include:

• Court expansion to balance out the current justices’ partisan skew;

• Stripping courts of jurisdiction to hear challenges to specific, or all, federal laws or regulations;

• Channeling jurisdiction to a specific court or other body;

• Supermajority or unanimity requirements, meaning courts can only strike down a law or regulation if a supermajority, or all, of its members agree; and

• An efficient way for Congress to correct court decisions misinterpreting federal law or regulations.

• The report also discusses other reforms which would complement these: ethics reform, shadow docket reform, lower court expansion, term limits, and laws to correct antidemocratic judicial doctrines like qualified immunity for civil rights claims and the “major questions doctrine.”

Congress could enact any of these through regular legislation, and many of them have been used multiple times before. For instance, Congress has changed the number of seats on the court seven times, and has passed hundreds of laws stripping courts of jurisdiction to hear challenges to specific laws or regulations. Nearly every U.S. state has term limits and/or mandatory retirement ages for high-court justices, as does every other constitutional democracy in the world.

Progressives should take some steps right away. They should support the Judiciary Act of 2023, which would add four seats to the Supreme Court. They should add jurisdiction-stripping, channeling, or supermajority language to every progressive bill to protect it from the courts. And they should work with Congress to write and build support for broader court reform legislation, including some or all of the tools described in the report, so that it is ready to go when it’s politically possible to enact it.

Some court watchers object to court reform on the grounds that it would harm the public’s respect for the judiciary. But the court’s low public approval rating is earned; Americans are correct to think that it acts as a partisan political body. Trying to prop up public support for the courts by ignoring glaring problems with them is not a solid basis for a system of government.

Some critics also object to shifting power from the courts to Congress. It’s true that Congress is currently ineffectual and populated by alarming extremists. But the problems with Congress are in part due to the court’s own rulings in areas like voting rights, campaign finance, partisan gerrymandering, and weakening the labor movement. Even with a highly imperfect Congress, it is healthier in a democracy for the public to be able to make policy demands of elected officials and democratically accountable agencies, rather than being limited to pleading their cases to unelected judges.

Progressives must not accept learned helplessness by deciding it is pointless to consider court reform because it is unlikely to be enacted in the short term, or because courts might strike it down. Progressives must build consensus on court reform now so that elements of it can be enacted when political conditions make that possible. Court reform has the potential to strengthen democracy and increase equality and justice. Enacting it will be difficult, but we must try. The ability of the American people to shape our future depends on it.