Supreme Court Decision Spares Potential Future Wealth Tax — For Now

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Supreme Court Thursday ruled not to redefine “income” — a move, pushed aggressively by Justice Neil Gorsuch during oral arguments, that would have headed off various wealth tax proposals that have gained steam on the left, and been a gift to the very wealthy and corporations.

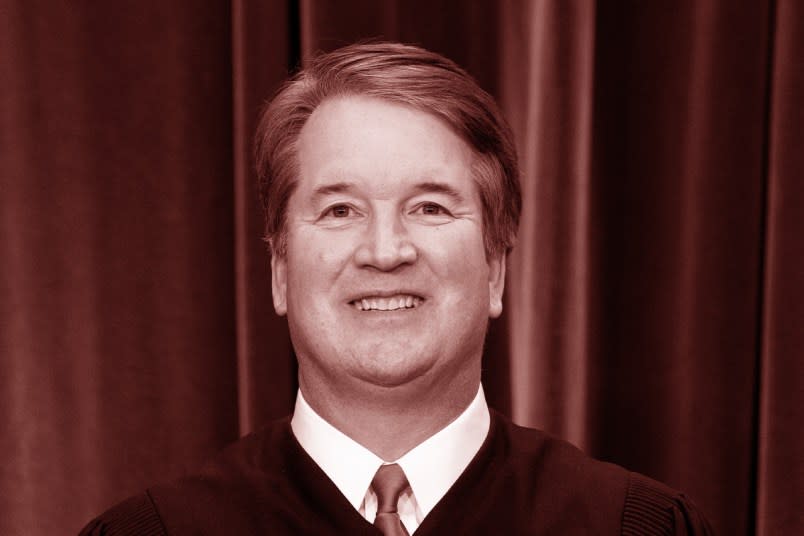

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote for the majority, in which all of the liberals joined. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson also wrote a solo concurrence; Justice Amy Coney Barrett concurred in the judgment, joined by Justice Samuel Alito.

Gorsuch and Justice Clarence Thomas dissented.

The case centers on a couple’s, the Moores’, attempt to wriggle out of a one-time tax on gains from a foreign company, which they were required to pay under a provision imposed by the Trump tax cuts of 2017. But there’s a reason such forces on the right as Wall Street Journal’s opinion pages, right-wing nonprofits and Alito’s favorite interviewer-turned-lawyer for the Moores got in on the action: redefining income like the Moores wanted would be a boon to ultra-rich people and institutions who benefit from alternative revenue streams.

Redefining income this way also would have required the Supreme Court to both ignore Congress and overturn its own precedent (something it has proven very willing to do on the right cases).

“Congress’s longstanding practice of taxing the shareholders or partners of a business entity on the entity’s undistributed income reflects and reinforces the Court’s precedents,” Kavanaugh wrote.

The case also put the Moores in the difficult position of arguing that the specific tax making them cough up around $14,000 (on over $500,000 in gains) was unconstitutional, while the many other taxes operating similarly are not.

“The Moores have advanced an array of ad hoc distinctions to try to explain why those longstanding taxes are constitutional and why those precedents are correct, and to simultaneously try to explain why those taxes and precedents do not eviscerate their argument that the MRT is unconstitutional,” Kavanaugh wrote, referring to the tax governing the case, the mandatory repatriation tax. “But the Moores’ effort to thread that needle, although inventive, is unavailing.”

“The upshot is that the Moores’ argument, taken to its logical conclusion, could render vast swaths of the Internal Revenue Code unconstitutional,” he added.

He echoed points made by Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar during oral arguments, noting that agreeing with the Moores’ elimination of all of those taxes would shift the burden to “ordinary Americans,” or those of us not huffy because we had to pay a fraction of our giant investment gains. Gorsuch (occasionally joined by Alito), during his oral argument performance, had taken great pains to repaint the case as one that posed an existential threat to the more meager wealth of the American everyman — clearly clocking the case’s unsympathetic main characters.

In a footnote, Kavanaugh hastened to say that Thursday’s decision should not be read as a ruling on or a judicial endorsement of a wealth tax, something the Court would consider in the future if Congress passed it. Coming down the opposite way, though, likely would have made imposing one virtually impossible — though foreshadowing in Moore positions many of the conservatives as preemptively hostile to such a tax.

In her concurrence, Jackson issued a mild warning to the Court, seeming to look to a future where Democrats may successfully pass one of the burgeoning wealth tax proposals.

“I have no doubt that future Congresses will pass, and future Presidents will sign, taxes that outrage one group or another — taxes that strike some as demanding too much, others as asking too little,” she wrote, adding that previous cases teach the justices “that this Court’s role in such disputes should be limited.”

Thomas and Gorsuch, the dissenters, also looked towards a future wealth tax — but as a frightening congressional power grab to which the Court has now made itself vulnerable.

“Even as the majority admits to reasoning from fiscal consequences, it apparently believes that a generous application of dicta will guard against unconstitutional taxes in the future. The majority’s analysis begins with a list of nonexistent taxes that the Court does not today bless, including a wealth tax,” Thomas wrote. “Sensing that upholding the MRT cedes additional ground to Congress, the majority arms itself with dicta to tell Congress ‘no’ in the future. But, if the Court is not willing to uphold limitations on the taxing power in expensive cases, cheap dicta will make no difference.”