The Supreme Court Just Opened the Door to New Second Amendment Chaos

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)

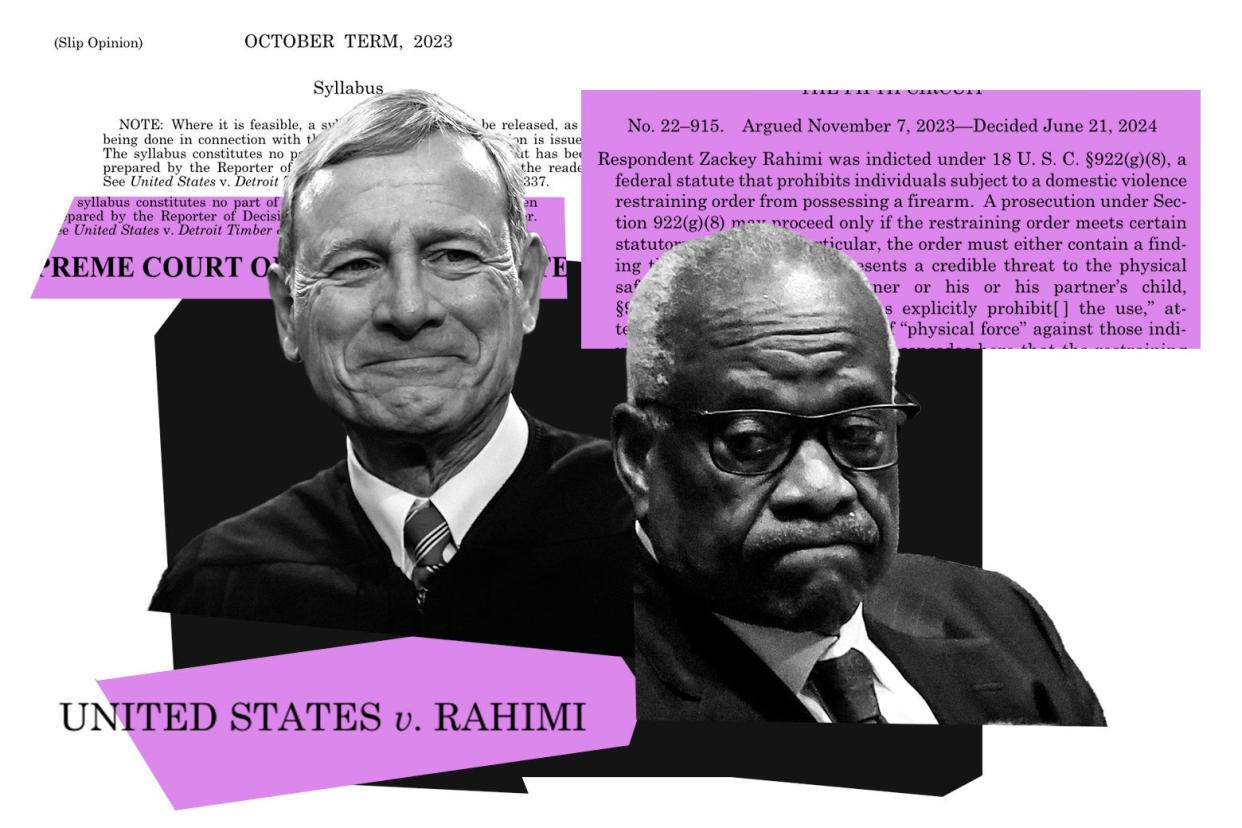

On Friday, the Supreme Court finally issued its decision in U.S. v. Rahimi, handing down 103 pages that can best be summarized as high-speed doctrinal backpedaling. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for a very fractured majority of eight, upheld a federal law that disarms domestic abusers, deeming it sufficiently rooted in “history and tradition.” Roberts painstakingly explained that while the court’s conservative justices are still very much gun nuts, they’re not in fact wedded to the insane version of originalism they adopted in their 2022 Bruen decision. That’s the opinion, authored by Justice Clarence Thomas, that reimagined judges as amateur historians, or perhaps costumed reenactors of the founding, striking down every gun restriction that doesn’t have enough “historical analogues” from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The court instead cleaned up Bruen’s mess, transforming the decision into something less radical and more practical, but took great pains to paint its decision as a gentle refinement for confused lower courts. Nonetheless, Roberts kept the court firmly planted in the gun rights arena, giving policymakers a new test—under the guise of reaffirming the old one—that will spawn all-new confusion. We have entered the era of living originalism, with more Second Amendment chaos around the corner.

On Saturday’s episode of Amicus, Dahlia Lithwick was joined by Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern and Kelly Roskam, director of law and policy at the John Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, to discuss what Rahimi means for gun safety in America. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dahlia Lithwick: I want to be really clear: This is not a win, this is a not-loss. Rahimi prunes back the worst of Bruen without doing much to help solve the catastrophic gun violence in the country. Last year, more than 40,000 people were killed by guns in the United States. Gun violence is now the No. 1 killer of children in America. Every month about 70 American women are murdered by a gun-wielding intimate partner. If her abuser has a gun, a woman is five times more likely to be killed by that partner.

Kelly, what does Rahimi change going forward in terms of what laws can be put into place and what measures can be bolstered? I mean, does this literally mean that every single domestic violence law that was in the crosshairs, so to speak, is now safe?

Kelly Roskam: There’s a lot that we need to do. When the opinion came out on Friday morning, I was incredibly relieved. But the bar is really low. If it had come out any other way, it would be absolutely devastating. I don’t think the Supreme Court gets any brownie points for doing the right thing here.

What it did not do—very specifically and very carefully—was say anything about an additional provision of the law at issue. The federal law prohibits people who are subject to protective orders from possessing guns. Some of these orders are issued after notice and a hearing against intimate partners, plus a credible finding of threat. But others don’t require that finding. The Supreme Court did not uphold protective orders where there is no credible finding of threat. That issue, I think, will percolate up through the courts.

Also, the majority did not discuss ex parte or emergency protective orders. Often, when individuals get protective orders, they first get an emergency order that is issued against an alleged abuser before they are given notice, and before they have the opportunity to participate in a hearing. That’s often the most dangerous time for individuals because it’s the first indication that an abuser is losing control over them. Many states across the nation also prohibit purchase and possession of firearms during that ex parte protective order period. We’re likely to see cases challenging that as well.

Lithwick: What about red flag laws? Those are laws that allow courts to temporarily disarm an individual if they’re alleged to pose a threat of physical violence.

Roskam: I do think Rahimi indicates that red flag laws, or extreme risk protection orders, are on safe constitutional ground, at least where they involve risk of harm to others. It’s less clear that these laws will be upheld when they’re issued because a person poses a risk of self-harm. Though the court repeatedly refers to prohibitions on persons with mental illness, which is a positive sign.

And apart from the constitutional aspect of this, implementation is incredibly important. It’s great to have the law prohibiting purchase and possession, but we need everybody who’s involved in that process to do their job. We need follow-up; we need to ensure compliance to really effectuate the promise of this protection.

Lithwick: Reading Roberts’ opinion for the court, I kept wondering: Is this what originalism is now? Bruen held out originalism to be locked in history, incredibly cramped, forcing judges to do nothing but become historians and to cherry-pick history. Rahimi feels like a win for the claim that all of that was a very bad idea.

Is there something, some glimmer of hope, in the fact that every conservative justice except Clarence Thomas backed off that incredibly punitive, dangerous view of originalism that he set forth in Bruen? And does that mean judges can now go back to doing whatever it was that they did until the 1990s when originalism became a thing?

Mark Joseph Stern: With regard to the Second Amendment, I think it’s going to be a mixed bag. It’s still going to be a choose-your-own-adventure situation in the lower courts. The 5th Circuit is probably not going to take the hint. The 5th Circuit is going to continue to churn out extremist decisions affirming a sweeping right to bear arms specifically for its favored parties, and it will need to be reeled back in by the Supreme Court.

One of the first things that’s going to happen is that the Supreme Court is going to take up a bunch of lower-court decisions on the Second Amendment, vacate them, send them back down for reconsideration in light of Rahimi. So we’re about to get a spate of second bites at the apple from the lower courts trying to apply this. And even though I’m grateful for what the chief justice did, and I’m glad that they have walked back the extremism of Bruen, there are still so many questions Kelly was pointing toward that just are not answered in this decision.

What about ex parte orders? What about red flag laws? What about self-harm and mental illness? Even in this relatively narrow category of potentially violent gun owners, there’s a lot we still don’t know. The courts are going to splinter, and the Supreme Court’s going to have to come back and provide an answer, and then another, and another. And the court’s going to stay stuck in this Second Amendment area where—as I think we proved in our originalism series—they have no right to be in the first place. There’s no legitimate justification for the Supreme Court to repeal the first sentence of the Second Amendment and transform a clause about the state militias being preserved after the ratification of the Constitution into this freewheeling, policy-driven right of individuals to keep and bear and travel with and use arms in self-defense. So Rahimi doesn’t solve the underlying problem. It closes one can of worms and opens a bunch more.

What I hope is that the court is so chastened by its experiment with originalism here that it won’t be overly aggressive in pushing originalism into other areas. And that was what Justice Amy Coney Barrett was hinting at in her opinion in that trademark case recently, where she splintered from the other conservatives and said, Look, we already have an established First Amendment framework, we don’t need to reinvent the wheel here and create some new kind of history and tradition test for free speech. I hope that Barrett has at least one more vote from the right in similar cases. But Justice Brett Kavanaugh spent many, many pages in Rahimi talking about why every other test is bogus and history and tradition is the only one that matters, so I’m not sure that a majority of the majority got the message it should have from Bruen’s fallout.

Lithwick: Kelly, we started this term saying that originalism, as constituted in Justice Thomas’ Bruen opinion, would not withstand Zackey Rahimi, the defendant in this case. And I think that’s true for the purposes of this Supreme Court. But it is not at all clear that that’s true for the 5th Circuit, or the other courts around the country who really, really wanna take us back to the founding.

Do you see Rahimi as a large-scale renunciation of a really bad idea? Or do you think the Supreme Court kind of embarrassed itself two years ago, and now wants to not look stupid? Because in some sense, the train has left the station and there are judges in courts around the country who don’t care what the Supreme Court thinks anymore.

Kelly Roskam: So on the Supreme Court’s part, I don’t think this is some massive renunciation of Bruen’s framework. I think the facts of the Rahimi case are the sword that cuts both ways. It was so bad, it was hard to conceive of the case coming out any other way than it did. As you know, Justice Barrett and several others at oral argument kept repeating that Zackey Rahimi was clearly dangerous. He was exactly the kind of person who shouldn’t have a gun.

Other cases, I think, are going to be a little bit closer. This decision may stem the massive flow from the dam, but it doesn’t provide any real clarity for other courts on how to find these general principles, and at what level of generality to define them. It’s clear that there’s this historical tradition of disarming people who judges have found are a credible threat to the physical safety of other people. But how do we piece together these analogues to find a greater purpose? There’s still so much opportunity for subjectivity all over every single substep of this test—which really flies in the face of what we were told in Bruen, which was that this is so objective and administrable. What we have after Rahimi is much more open to interpretation and personal preference on the part of judges.