The Supreme Court Just Opened the Door to the Criminalization of Disability

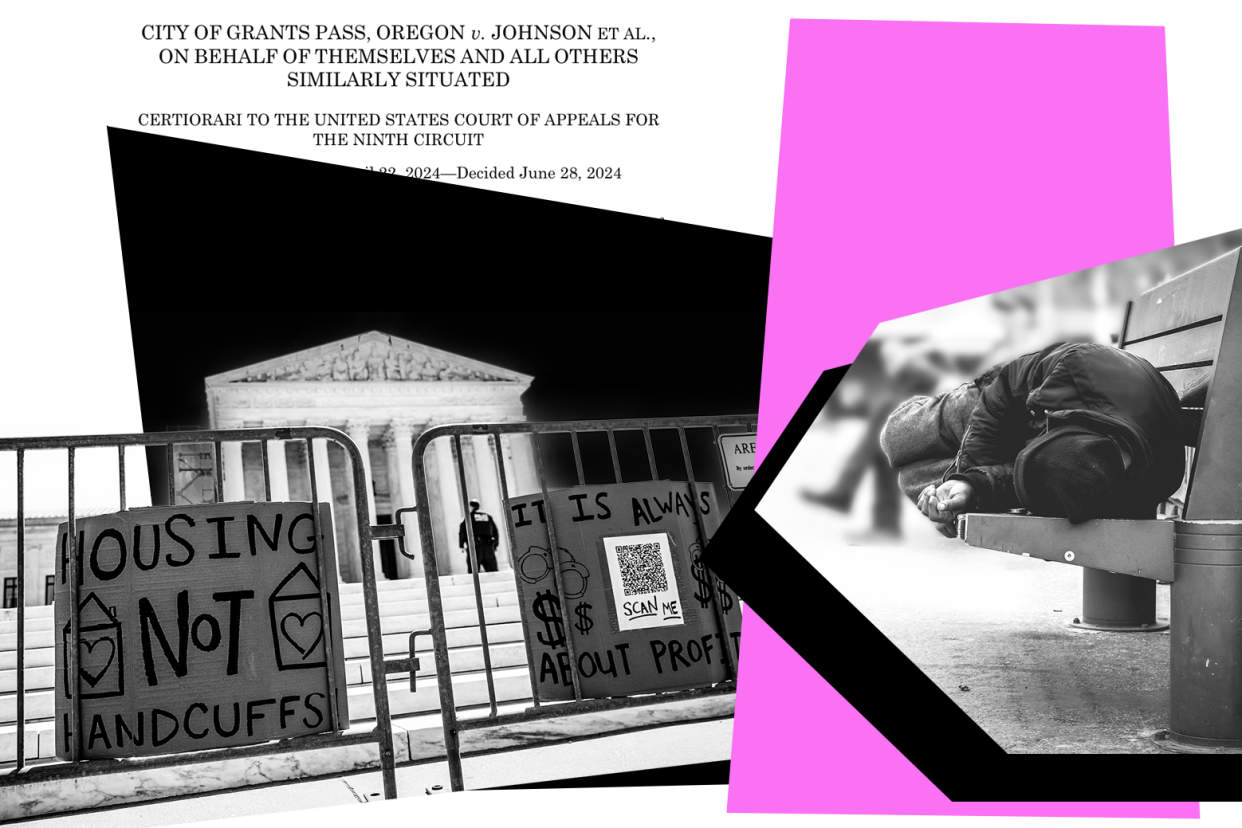

In a 6–3 ruling, the Supreme Court just held that people experiencing homelessness could be subject to criminal and civil penalties for sleeping in public spaces. In City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, the court overturned a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, which had held that these penalties were unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. This case stemmed from Grants Pass, Oregon, where local politicians were seeking to eradicate the homeless population through fines and jail time.

As a disability rights lawyer who has a disability, I know that this decision will devastate my community. People with disabilities are disproportionately likely to experience homelessness. Data reveals that 78 percent of homeless people report having mental health conditions, and an estimated 52 percent of homeless adults in shelters nationwide have a disability. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities in particular face a housing crisis with many contributing factors, such as a serious lack of safe, affordable, accessible, and integrated housing, and significant housing-related discrimination. Outdated public policy and programs unnecessarily segregate people with IDD, and community-based programs are frequently underfunded. Likewise, the lack of physically accessible and affordable housing pushes people with disabilities who rely on Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income into homelessness. Only 6 percent of homes nationwide are wheelchair accessible.

People with disabilities are at the heart of the Grants Pass case. At the trial court level, multiple people submitted declarations that they were not able to stay at the only shelter in Grants Pass because of their disqualifying disabilities. For example, CarrieLynn Hill could not stay at the shelter because it banned residents from using the nebulizer she needed regularly in her room. Debra Blake’s disabilities prevent her from working, and she could not comply with the shelter’s requirement to work 40 hours a week. Hill and Blake are examples of the impossible choices faced by so many homeless disabled people. They cannot be at the shelter, but they risk prosecution under the ordinances if they remain unhoused.

Faced with criminal sanctions for not having a place to live, Hill and Blake, alongside other homeless people, sued Grants Pass because they felt that the ordinances amounted to cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. They relied on Robinson v. California, a Supreme Court decision from 1962. In that case, the court held that the Eighth Amendment bars state and local governments from criminalizing a status, such as being addicted to drugs.

In Robinson, the court based its decision partially on an understanding that the Eighth Amendment bars the criminalization of disability. Writing for the Robinson majority, Justice Potter Stewart declared, “It is unlikely that any State at this moment in history would attempt to make it a criminal offense for a person to be mentally ill, or a leper, or to be afflicted with a venereal disease.” Even in the early ’60s, the court recognized that the criminalization of disability was unconstitutional.

This was a groundbreaking decision. From the 1860s to 1972, cities in the United States succeeded in criminalizing disability through so-called ugly laws. These horrific ordinances prohibited disabled people from existing in public. For example, an 1881 Chicago ordinance provided that “no person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object or improper person [is] to be allowed in or on the public ways or other public places in this city.” Professor Susan Schweik has documented how this type of ordinance was enacted in cities across the country. In essence, ugly laws were designed to suppress disabled bodies (including “unsightly” beggars). Such legislation was obviously unconstitutional post-Robinson because it criminalized the status of being “diseased” or “maimed” in public.

Yet in Grants Pass, the Supreme Court has sent the Eighth Amendment back to the 19th century. Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch distinguished the case from Robinson, claiming that the ordinance in Grants Pass prohibits only actions like sleeping outside, regardless of housing status. The opinion implicitly overrules Robinson by casting it as an outlier that “sits uneasily with the [Eighth] Amendment’s terms, original meaning, and our precedents.” The opinion contains no reference to disability, even after a group of 24 disability rights groups filed a friend-of-the-court brief urging the court to consider how Grants Pass’ ordinance criminalizes being disabled and homeless. My organization, the Arc of the United States, proudly signed on to this brief.

In contrast, Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent recognizes the effect these ordinances have on the disability community, citing extensively to our amicus brief. Because of the lack of accessible housing, she writes, “it is unsurprising that the burdens of homelessness fall disproportionately on the most vulnerable in our society.” Sotomayor also centers the stories of Hill and Blake and deftly undermines the majority’s reasoning.

Grants Pass’s Ordinances criminalize being homeless. The status of being homeless (lacking available shelter) is defined by the very behavior singled out for punishment (sleeping outside). The majority protests that the Ordinances “do not criminalize mere status.” Saying so does not make it so. … The Ordinances’ purpose, text, and enforcement confirm that they target status, not conduct. For someone with no available shelter, the only way to comply with the Ordinances is to leave Grants Pass altogether.

Grants Pass is one of several cases in this and previous Supreme Court terms that significantly affect the rights of people with disabilities—even when disability may not be the central theme or be explicitly addressed. Applying this “disability lens” to the Supreme Court is critical in understanding the broader impact these decisions have on the lives of people with disabilities nationwide.

The disability rights groups argue in their brief, “Criminalizing the involuntary conduct of being a homeless person without a place to sleep—in a city with no public shelters—is anathema to the decency standards of any civilized society.” Yet the court’s decision in Grants Pass allows localities to punish, as Sotomayor writes, “the very existence of those without shelter,” including those with disabilities. For her part, Sotomayor remains hopeful “that someday in the near future, this Court will play its role in safeguarding constitutional liberties for the most vulnerable among us.” In the face of this decision, the disability rights bar will continue to fight alongside people with disabilities to ensure that the promise of constitutional and federal disability rights protections are realized to the full extent of the law. Even when Supreme Court decisions may be inconsistent with the guarantees of these laws, it is critical that courts—and the general public—understand what is at stake.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)