Two decades ago, Republicans chose to attack environmental regulations. Now we're paying the price

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When the Supreme Court ruled against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on Thursday, June 27, it incurred the ire of many analysts. At issue in the case of Ohio v. EPA was whether the agency can implement a plan to limit cross-state air pollution via the Clear Air Act while affected states challenge its legality. By ruling that the EPA lacks this power, the Supreme Court — according to University of Michigan law professor Rachel Rothschild — "reflects two longstanding trends in his environmental law jurisprudence: deep skepticism of agency experts and emphasis on state authority over environmental protection." California Democratic Party Executive Committeewoman Christine Pelosi was more blunt, tweeting that "polluters pay big money, win big rulings."

While it is bracing for the Supreme Court to act like this, it is sadly not a new trend. Both of these trends — denying scientific expertise and siding with "big money" over common sense — began in the early 21st century, when powerful political leaders realized humanity's excessive release of greenhouse gases was dangerously overheating the planet.

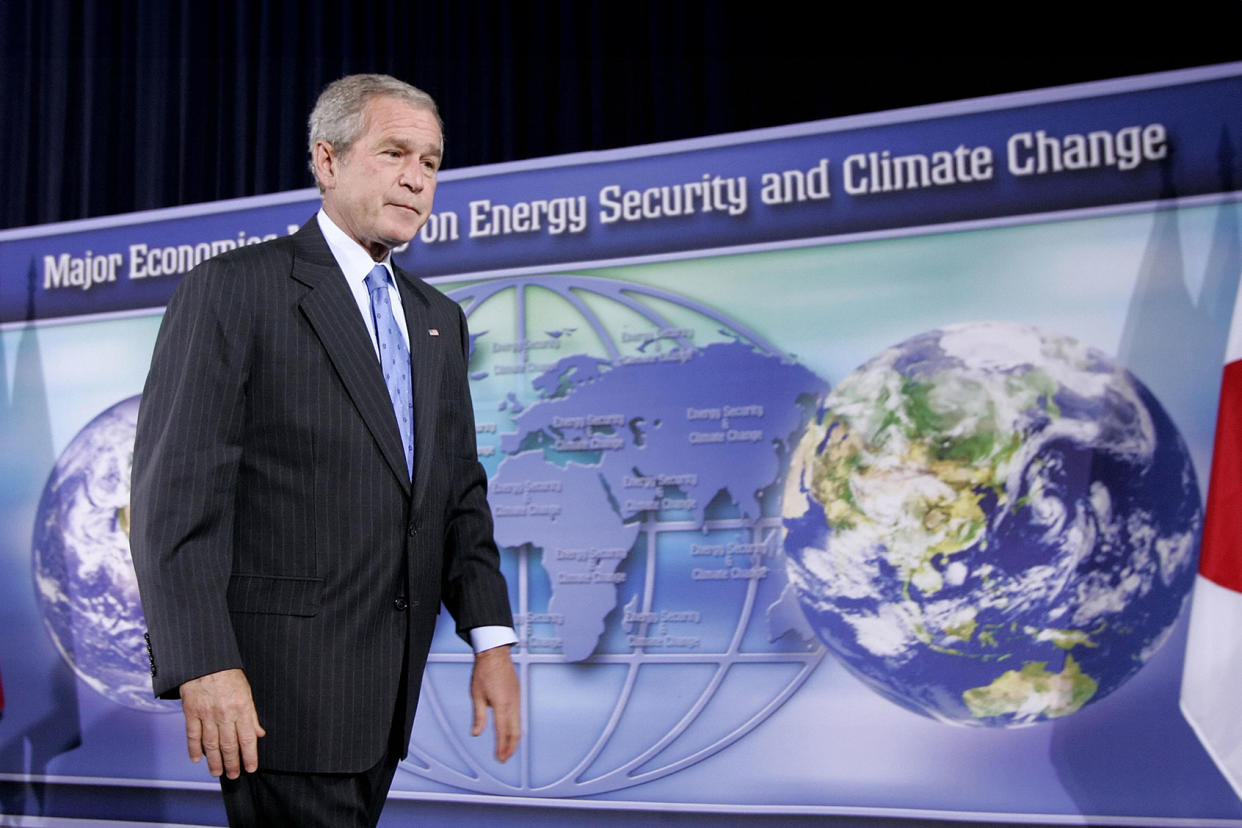

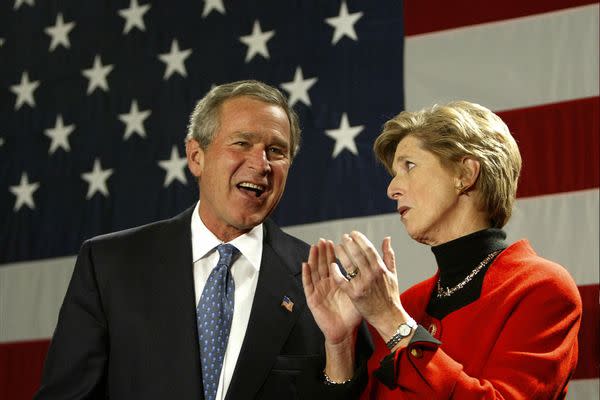

More than 20 years ago, a historic battle within the White House over how to classify carbon dioxide had profound reverberations that humanity still feels today in the form of climate change worsening and science denialism increasing. It took place during the height of the George W. Bush Administration, when the head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was a famously moderate Republican, former New Jersey governor Christine Todd Whitman, who eventually left the agency out of frustration.

If the saga of human-caused climate change could ever be boiled down to a single moment, one that foreshadowed the dark future that lay ahead, it was the dramatic story that culminated in Whitman's resignation.

Whitman understood that carbon dioxide needs to be regulated as a pollutant, and anti-environmentalists could hardly argue that she felt this way because she is a tree-hugging hippie. Descended from a dynasty of New Jersey Republicans, she had worked for the Republican National Committee and helped found the Republican Leadership Council (then known as the Committee for Responsible Government). As New Jersey's governor she had a reputation as a centrist, and when Whitman agreed to be Bush's EPA head, she did so from the understanding that the Texas governor had characterized himself as a fellow moderate, particularly on environmental issues.

Being a moderate included an ability unusual in politicians — namely, to admit to their own mistakes. Whitman did this years after leaving the EPA by apologizing for incorrectly claiming the air around Ground Zero was safe to breathe after the Sept. 11th terrorist attacks. When she departed the EPA, environmentalists criticized Whitman's tenure by alleging she was too pro-business, as well as too willing to delegate powers to the states.

However, criticisms also came from her own party because she did things like follow scientific data. As Whitman told Salon, among individuals like Cheney "there was just a questioning of the science, of how real is this, and aren't we being a little Chicken Little?"

Whitman was adamant about heeding her science advisers' warnings about climate change, who insisted that carbon dioxide emissions were overheating the planet. Whitman's stance on that issue — and, as a consequence, about air pollution overall — is what would ultimately lead to her decision to leave the Bush administration.

"As governor, [Bush] had put a cap on carbon, and it was in his campaign platform," Whitman told Salon. He made it clear from the beginning that he would not take bolder steps, such as joining the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty limiting greenhouse gas emissions by extending the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. At the same time, Whitman "made sure with the White House that it was okay to say that, while we weren't endorsing Kyoto, we would be regulating carbon. But when I got back, that was when the pushback happened."

Cheney took a letter up through Capitol Hill that had been composed by senators opposed to regulating carbon emissions. California had been in the throes of widespread brownouts due to an energy crisis when Bush took office in 2000, and continued to grapple with that crisis during his first year in 2001. People worried there would be blackouts. Bush set up an energy task force and assigned Cheney as its chair.

"It was evident from the very beginning that the focus was on the EPA and regulation," Whitman recalled. "They tried to take the Clean Air Act enforcement away from the agency and give it to [the Department of Energy], which obviously I pushed back on, and they did not do it. But [Cheney] was still not a big fan, shall we say, of regulating the energy industry."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Yet the Cheney-Whitman feud over energy regulation didn't end there. As Whitman explained, it wasn't easy implementing the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon dioxide pollutants because it made an exemption for emissions caused by routine maintenance, repair and replacement for businesses trying to comply with reforms. Under Bush's predecessor, President Bill Clinton, the EPA had "pulled in a lot of the small power companies that had been doing things they thought were the right way. Actually, they had been; it was the big guys who were gaming the system. So we needed to have a definition of what was routine."

Whitman recalled the next two-and-a-half years, going "back and forth on numbers, on what the scientists could come up with that was reasonable, which would capture the bad actors but recognize those small guys that were just repairing or replacing and weren't secretly increasing their output, which is what a lot of the big guys were doing."

Unfortunately for environmental protection efforts, the two sides couldn't come to an agreement and matters eventually reached a climax.

"Finally, the administration handed me a set of numbers and they said, 'This is where we should set it,'" Whitman said. "I went back to the agency and said to our scientists, 'Can you justify this in any way? And they said, 'No.' So I went back to the administration and said, 'Look, this is your policy, your administration, I can't see this regulation and I can't enforce it. So you need somebody there who will.' And that's what happened."

Whitman was replaced by another former Republican governor, Mike Leavitt of Utah, who served for an additional two years.

"The reason I left was over the Clean Air Act and a definition within that, but also I was getting to the point where I was losing more than I was winning, and certainly climate change was one of [those issues]," Whitman said. Her setbacks did more than harm the environment in the immediate sense — they also helped normalize the outright denial of climate science within the mainstream Republican Party.

As University of Pennsylvania climatologist Michael E. Mann previously told Salon, "in terms of like the party's official stance being the rejection of environmental science — climate science, ozone depletion, what have you — that really hit its stride during the George W. Bush years. That is the transition when Dick Cheney and the energy industry took over energy and environmental policy for the George W. Bush presidency. That's where they really veered sharply in the direction" of outright denialism.

Michael Oppenheimer, a Princeton University professor of geosciences and international affairs, elaborated on the ecological consequences of this denialism.

"From the a point of view on the climates issue alone, it is not only that was there no progress; there was regression," Oppenheimer told Salon, pointing to the spike in carbon dioxide emissions that occurred since the advent of the 21st Century. As long as Bush deferred to Cheney on energy policy, which he did through his entire eight years in office, the pro-science and centrist approach of people like Whitman was subordinated by the belief that environmentalists stood in the way of energy industry profits. The situation did not change until Bush was succeeded by President Barack Obama in 2009. At that point, Obama could appoint EPA leaders who supported regulating carbon dioxide and could fall back on a recent Supreme Court case, 2007's Massachusetts v. EPA, which argued that the EPA was required to regulate greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Clean Air Act.

"Obama benefited from the Supreme Court having made the decision in Massachusetts v. EPA, which gave the federal government the authority, without even changing a word, within Clean Air Act to control carbon dioxide, initially from motor vehicles and later across the whole economy," Oppenheimer said, adding that both this and subsequent Supreme Court and lower court decisions "validated efforts by California and other states to regulate greenhouse gas emissions as air pollutants and applied that finding first to automobiles, and later to electric power plants and other human made sources. For this and other reasons, particularly the declining price of natural gas, U.S. emissions of CO2 and total GHG emissions peaked in 2007 and began to fall, partly because industry anticipated more state and federal regulation now that CO2 was classified as an air pollutant."

Yet when President Donald Trump took office, these Obama regulations were either weakened or completely reversed. Now the Biden Administration is in the process of restoring these regulations, in a somewhat different form, Oppenheimer explained, "While at the same time pairing the rules with ample subsidies and tax breaks with the goal of electrification based largely on carbon-free generation."

"Other countries took note, particularly when the U.S. and China signed a bilateral agreement in 2014 with specific emissions targets," he continued. "This helped create the international consensus that developed the Paris Agreement in 2015. Since then, many countries, but not all, have put serious plans to cut GHG emissions in place, even if implementation has been slower than the original intent indicated in those commitments."

In his opinion, Oppenheimer said that without "the state actions to treat CO2 as an air pollutant, the 2007 [Supreme Court] decision, and the subsequent Federal regulations, much of the progress since 2007 on U.S. emissions, and to a lesser extent on turning around the growth of global emissions, would not have occurred."