When ‘universal’ pre-K really isn’t: Barriers to participating abound

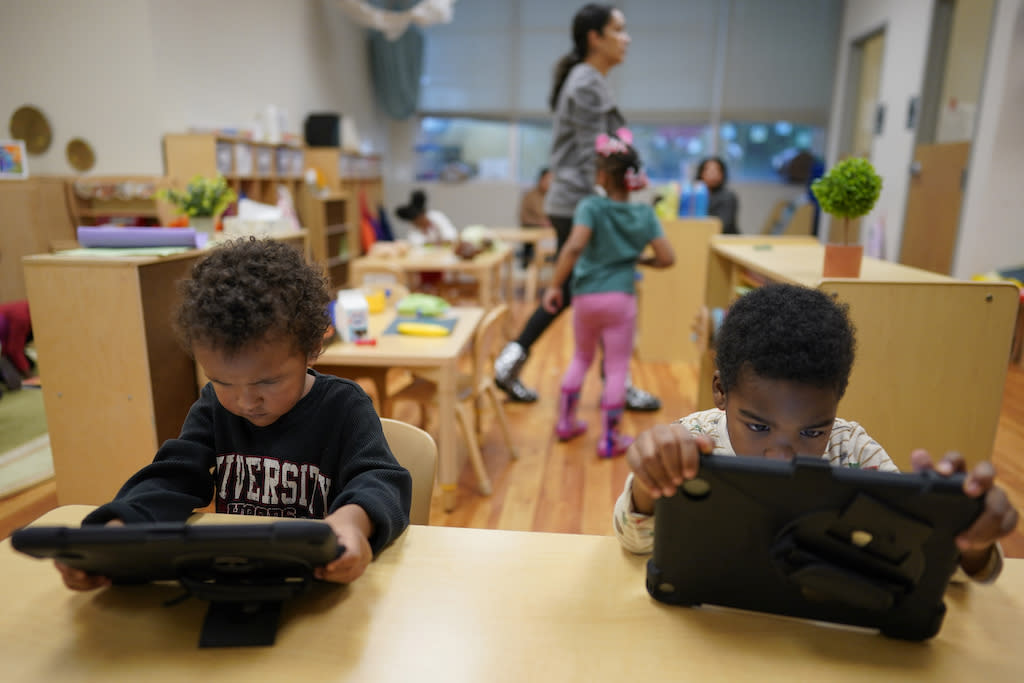

Children work on tablets during a preschool class in Cincinnati in 2023. Many states are expanding pre-K, but there are barriers to attendance for many families. (Carolyn Kaster/The Associated Press)

When Tanya Gillespie-Lambert goes to an event in a local park in Camden, New Jersey, she takes a handful of brochures about free preschool with her. She has no hesitation about approaching strangers — moms with kids especially — to plug the service in the local public school district, where she’s director of community and parent involvement.

Gillespie-Lambert and her team also hold door-knocking events several times a year to put the word out on free pre-K, dressing up in matching blue T-shirts and hats. That’s in addition to billboards, public service announcements and posters all over town.

“I still get a little shocked when they don’t know about it,” she said in an interview. “They always say, ‘I didn’t know they could start when they were 3 years old, and they don’t have to be potty trained. And it’s free?’”

Forty-four states offer some free preschool, and states from Colorado to Mississippi are expanding their programs. But even when states claim to have “universal” pre-K for 4-year-olds and sometimes 3-year-olds, some of the most comprehensive programs only serve a slice of the kids who are eligible.

There’s a host of reasons for that, beyond a lack of awareness.

Some states only provide funding for 10 or 15 hours of preschool per week. Some parents can’t afford the cost of before- and after-care or have transportation problems if there’s no bus. In some states, private pre-K providers, who often get state money for their pre-K programs, oppose shifting more state funds to public schools. And many states have a shortage of early education teachers and assistants, limiting the number of slots they can provide.

In South Carolina, the state provides full-day 4K for children who live in poverty or have other “at-risk” factors, such as developmental delays. The full-day program started as a pilot in 2006 and gradually expanded statewide. The state funds it in both public schools and private providers.

For the coming school year, the Legislature allocated more than $137 million toward full-day 4K, up from $76 million in 2019-20, according to budget documents and the latest report on South Carolina’s program.

Studies show preschool is highly beneficial for young children, giving them a jump on reading and math skills and the socialization that are key to later school success. Preschool differs from child care, which has less emphasis on academics and often doesn’t employ certified teachers. But private preschool is costly, making it difficult for parents with lower incomes to afford pre-K unless it’s state-funded.

“Everybody doesn’t define ‘universal’ the same way,” said Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University. “You can’t just wave a magic wand.”

Barnett said a state pre-K program should not be considered universal if there’s a cap on funding or a waitlist for slots. He advocates for states to treat pre-K like first grade — automatically available. But providing universal preschool is expensive for states.

Participation varies

More than 1.6 million 3- and 4-year-olds attended state-funded preschools in the 2022-2023 school year, with states serving 7% of 3-year-olds and 35% of 4-year-olds, according to Barnett’s institute.

But participation varies widely from state to state. The number of 4-year-olds enrolled in state-funded pre-K programs in the 2022-2023 school year ranged from a high of 67% in Florida, Iowa, Oklahoma and West Virginia to single digits in Alaska, Missouri, Nevada, Delaware, North Dakota, Arizona, Hawaii and Utah, according to the institute.

Last year, the institute ranked South Carolina 11th nationally in access to 4K.

Six states have no state-funded preschool: Idaho, Indiana, Montana, New Hampshire, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Some states are starting pre-K programs or expanding them. Mississippi doubled the number of kids in preschool in 2022-23 from the previous year to more than 5,300, added another 3,000 seats in 2023-24 and committed to future expansion, according to the state.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, signed a universal preschool bill in April 2022, and classes started in the 2023-24 school year. But Colorado’s program provides only 15 hours of free preschool per week in the year before kindergarten.

Similarly, Vermont’s universal pre-K program, enacted in 2014, provides only 10 hours a week of free school.

In addition to being problematic for parents who work 40 hours a week, 10 hours a week of preschool is not enough to provide quality learning, Barnett said. “It has to be a big enough dosage … of truly high-quality education.”

Everybody doesn’t define ‘universal’ the same way. You can’t just wave a magic wand.

– Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University

Vermont state Sen. Ruth Hardy, a Democrat, called the program “technically universal” because all 4-year-olds are allowed to participate but acknowledged there are gaps. She filed a bill last year that would have expanded the pre-K program to include full school days but it died, amid other expansions to child care and educational priorities.

Hardy, a former educator and school board member, said in an interview that the legislature did enact a measure to study expanding pre-K to all 3- and 4-year-olds and report back by July 2026.

It was part of a larger law that focused on providing more child care subsidies, including for families with incomes up to “middle-class or close to upper-middle-class levels,” she said. To pay for it, the state instituted a new payroll tax of 0.44%. Employers may choose to pay all of it or deduct up to 0.11% of it from employees' wages.

Concerns about access

Hardy said that in Vermont, as well as other states, a roadblock to expanding public pre-K programs is the “tension” between public and private schools. Many states take a “mixed delivery” approach to public preschool, under which pre-K is offered in settings ranging from public schools to community-based centers to private schools. But private providers sometimes see expanding the public preschools as competition.

Aly Richards, CEO of Let’s Grow Kids, a Vermont child care advocacy organization, said the group’s concern is equitable access to pre-K programs, especially when parents need kids in all-day instruction and public programs only operate on school-day hours, while private programs often last all workday.

“Working-class families can’t leave their job in the middle of the day if they have to move their kid,” she said.

She also said there is often not enough room in nearby public schools to accommodate all the children who want pre-K programs.

Similar tension is roiling efforts to expand public pre-K in Michigan. Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Democratic lawmakers want to make more children eligible, but private schools worry that legislative proposals would eliminate requirements that a percentage of slots go to private providers and thereby cut their state funding.

In Hawaii — which has one of the highest-quality public preschool programs, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research — the problem is getting enough educators into the classrooms.

Hawaii plans to open 44 more classrooms for 3- and 4-year-olds in the fall, bringing the state’s total to about 90, Lt. Gov. Sylvia Luke, a Democrat, said in a statement. But more staffing is needed if the state is going to reach its goal of getting all 3- and 4-year-olds in preschool by 2032, The Associated Press reported.

California is in the third year of a four-year phase-in of a universal pre-K program launched in the 2021-22 state budget. A draft report from the Learning Policy Institute, a California educational research group, found that while most school districts in the state are on track toward getting all 4-year-olds and income-eligible 3-year-olds in pre-K, staffing is a problem and is expected to get worse as new teacher requirements go into effect.

Hanna Melnick, a senior policy adviser at the Learning Policy Institute and one of the co-authors of the report, said it’s unclear how many of the eligible kids are actually taking advantage of the pre-K program.

Some families can’t afford before- and after-care, she said. “Extended care is a really critical barrier. And some families want more of a family-like environment [for their preschoolers]. They might not feel comfortable using out-of-home care or care in a school setting.”

In South Carolina, children participating in state-funded 4K at private providers automatically qualify for scholarships for free before- and after-school child care. The free child care covers not only the children in preschool but all of their siblings 12 and under.

Back in New Jersey, Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy announced in March that an additional $11 million in state funding had been secured to bring preschool to 16 more school districts in the state.

But despite the effort, workers such as Gillespie-Lambert need to keep walking neighborhoods.

“People don’t read,” she said. “We found canvassing — not just flyers, but having a conversation with them — seems to work a lot better.”

What SC's doing to increase participation for eligible 4-year-olds

In South Carolina, the state pays for full-day 4-year-old kindergarten for children designated "at risk." That's defined as children who qualify for Medicaid or free and reduced-price meals, as well as those who are homeless, in foster care or show developmental delays.

However, public school districts can, and many do, choose to use local property tax dollars to supplement state aid and expand eligibility to more children of parents with higher incomes.

It's a dual system in South Carolina, with the state Department of Education overseeing 4K programs in public schools, while First Steps — a separate agency created 25 years ago to help prepare children for school — oversees state-paid classes in approved, private schools and child care centers. Parents can choose either option, where slots are available.

South Carolina's state-paid 4K program dates to 1984, when the Education Improvement Act funded a half-day program for poor 4-year-olds.

The Legislature began paying for full-day 4K classes in 2006 in response to a court decision in a long-running education funding lawsuit. But it was launched only as a pilot program for at-risk children in the poor, rural school districts that sued the state 13 years earlier. The Legislature gradually expanded availability.

By 2023, the state-funded program was offered statewide, though four school districts still chose not to participate. Lack of additional classroom space in some public schools was one reason legislators cited in creating the dual public-private system from the outset. Another reason is that private providers didn't want to lose their customers.

As of last November, just over 200 children were on waitlists at 12 public schools, according to the state Education Oversight Committee's most recent annual report on the state’s 4K program.

The report, issued in March, estimated that around 21,400 children, or about 60% of the total number of children living in poverty in the state, did not participate in any of the state’s 4K programs during the 2022-2023 school year.

That number is down from 72% of eligible children not participating during the prior school year.

But First Steps continues to work on bringing it down further, said spokeswoman Beth Moore.

One major barrier, officials found, was that parents didn’t know what was available or how to enroll, so they would skip the program altogether, she said.

Since 2020, the Early Childhood Advisory Council has introduced two different portals to help parents determine what programs their children qualify for — a system other states have mimicked.

Palmetto Pre-K, launched in 2020, tells parents whether they’re eligible for state-funded preschool programs. First Five SC, launched two years later, does the same but includes all early childhood programs with federal or state funding, as well as a host of other assistance programs, such as other child care options, health care, food assistance and parenting support, Moore said.

Since May 2023, parents have been able to fill out a single application on first5sc.org to apply to dozens of programs.

Because preschool options can vary among counties or school districts, the portals cut down on the time and effort it might take parents to navigate an otherwise confusing process, Moore said.

Plus, any student who qualifies for First Steps 4K automatically qualifies for a Department of Social Services scholarship to cover child care costs before and after school. That means that if the school day ends before a child’s parent gets off work, they don’t have to worry about paying for the gap in time, Moore said.

Since 2021, the scholarship has applied to all siblings in a household who are 12 years old or younger, not just the student in preschool. That cut down on another barrier in enrolling children in 4K: When a parent would have to stay at home with other children, they often decided not to send one off to preschool, Moore said.

However, some barriers remain.

Along with getting the word out about what’s available, First Steps is trying to find more ways to incentivize additional private schools and child care centers to sign up. Because the state money often doesn’t match what a private provider could be making through tuition or regular daycare charges, that can be difficult, Moore said.

On top of offering extra coaching and resources to its contracted preschools, First Steps 4K is looking for other benefits that could encourage more centers to take children on the state’s dollar and help the program continue to expand, she said.

The number of classrooms available has been improving in recent years.

During the 2022-2023 school year, First Steps 4K operated in 279 classrooms in private child care centers and private schools in 40 of the state's 46 counties. That's an increase from 265 classrooms the year before, according to the annual report.

Including public schools, the state funded 1,160 preschool classrooms statewide during the 2022-2023 school year, the latest data available. That's up from 888 total three years earlier, according to the yearly report by the Education Oversight Committee.

In South Carolina, 3-year-olds with disabilities and developmental delays are eligible for public preschool. But slots for the federally funded program are very limited.

During the 2022-2023 school year, 2,593 3-year-olds received special education services through the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act grant program.

_Skylar Laird, SC Daily Gazette

Like SC Daily Gazette, Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org. Follow Stateline on Facebook and X.

The post When ‘universal’ pre-K really isn’t: Barriers to participating abound appeared first on SC Daily Gazette.