How Venezuelans in Miami, unable to vote Sunday, are playing a role in pivotal election

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

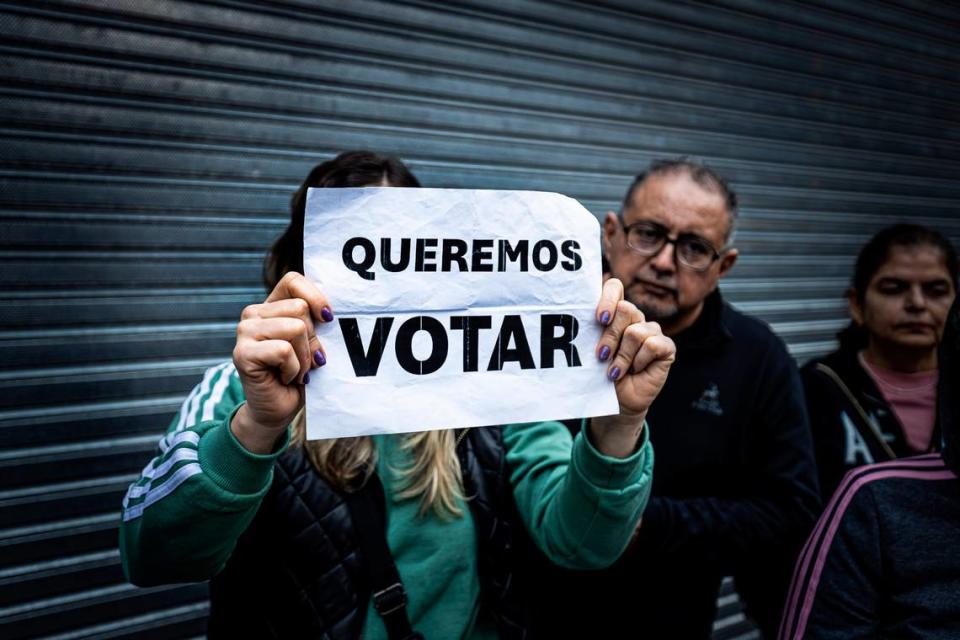

Unable to vote in Sunday’s pivotal presidential election in Venezuela, Venezuelan exiles in the United States are nevertheless organizing to play a role by recruiting friends and family members to be part of an army of observers to help safeguard the vote in their home country.

Helping to build this network of unofficial election observers, organized around what are being called comanditos — little command centers — from Miami and other U.S. cities has had by necessity a clandestine feel, because participants in Venezuela will risk harassment and even arrest by security forces of the Nicolas Maduro regime.

“This is risky work,” said a top organizer in Miami, who asked to remain anonymous because of his sensitive work in Venezuela. “We are trying to organize an election inside of a failed state, with areas controlled by leftist guerrillas as well as crime bosses allied to those heading the government, to compete against a regime whose security forces treat those challenging them in the election as if they were committing a crime against the state.”

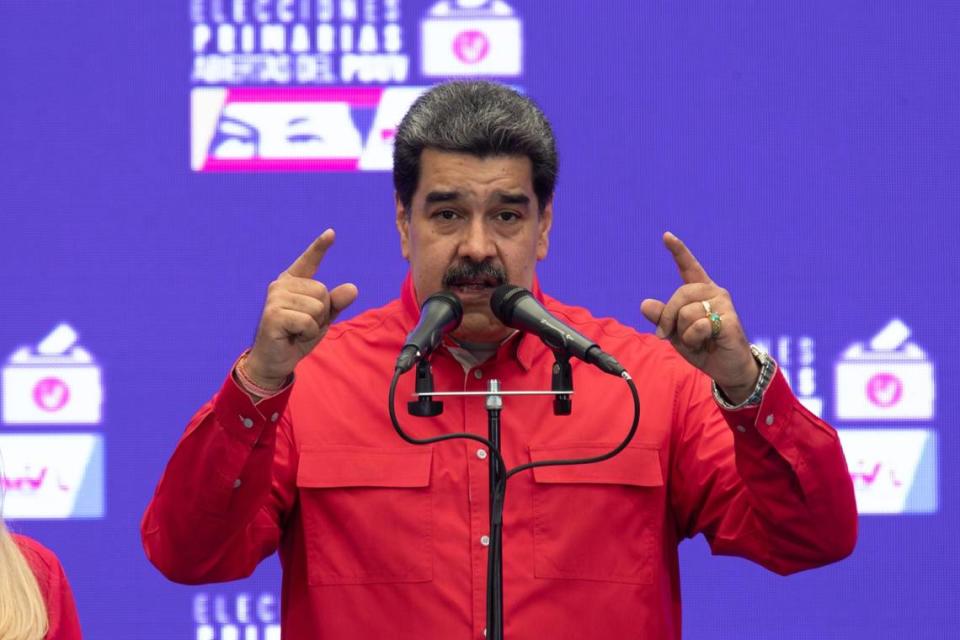

As Maduro heads towards a crucial election that could put an end to his rule — he’s behind as much as 40 points in most respected polls — his security forces have redoubled efforts to clamp down on supporters of opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez and of his mentor, opposition leader María Corina Machado.

In the past few weeks security forces have arrested more than 100 volunteers from the Gonzalez campaign, freeing some of them soon after but keeping a number of them in prison.

For those inside Venezuela who are being asked by friends and family members in the U.S. to get involved in the election, becoming part of the election-monitoring network being organized by the opposition carries an unquestionable degree of risk.

“It might not automatically land them in jail, but some of them might be risking their access to medical care or to subsidized food or gasoline,” said the Miami organizer.

In some cases, campaign volunteers may even have their property confiscated, as was the case of a car mechanic who recently lost his truck and had his shop raided because he dared to lend a vehicle to the opposition’s campaign so Machado could travel inside the country, he added.

If the regime does decide to make an example of them, volunteers could be arrested by Maduro’s feared intelligence services, which have frequently been accused of torturing political prisoners.

Knowing that the overwhelming majority of Venezuelans in the United States would vote for the opposition, the Caracas regime has made no effort to allow them to vote. In the past, Venezuelan exiles have been able to vote at locations rented by their country’s consulates in the U.S., but there are currently no diplomatic relations between the two countries.

More than 800,000 Venezuelans are currently believed to be living in the U.S., forming part of the 7.7 million-strong wave of people who have fled the socialist government.

The comanditos are expected to play a key role in the opposition’s efforts to win the election by serving as support groups to voters having difficulties in getting to polling stations, and by having members staying at polls after they close to keep regime members from trying to manipulate the count.

Given the pronounced scarcity of everyday goods in Venezuela, the organizers have emphasized providing the army of volunteers with food and fuel to give to potential voters on election day.

Most of the U.S. efforts to help form the comanditos have been undertaken quietly, in many cases informally, by Venezuelans who are well aware of the risks.

The organizing effort is worldwide, with Venezuelan exiles in many other countries taking part. But there is a particular stigma attached to any help coming from Venezuelans in the U.S., which raises the stakes of the organizational work. Miami, for example, has often been described by the Caracas regime as a nest of terrorists plotting to topple the Maduro government.

Sensing that Sunday’s election might be the last chance the country has to restore democracy, many Venezuelans in the U.S. say they refuse to be uninvolved.

“After they denied us the right to vote, I proceeded to start organizing the comanditos,” said Miami resident Petra Figueroa, who sought refuge in the U.S. after becoming escaping an assassination attempt in Venezuela for her political views.

A retired college professor, Figeroa, 61, said she began contacting her former students through social media, encouraging them to get involved in the election. “I started building these ‘groups of conscience’ among these young people, who have only lived under this dictatorship. So I started convincing them not only of the need to vote but to get involved and create their own comanditos.”

Reaching out to former students, sometimes at odd hours to get around the frequent electricity blackouts and interruptions in internet service, she has been able to get around 125 of them to get involved, along with an additional 50 friends and family members.

Euridice Rodríguez, 61, who lives in Branson, Missouri, has helped organize voters in the central Venezuelan town of San Juan de Los Morros.

She got involved, she said, because the Caracas regime has stripped Venezuelans of their freedom to choose. “Liberty is the most beautiful right given to us by God and this regime has wanted to take it away from us.”

Deciding that they could help, even from Missouri, Rodríguez and her group have been sending money for food and fuel to 60 different comanditos in Venezuela and reaching out to those unsure about the election about the need to vote.

Carolina Mercedes Barreto, 58, has been providing assistance from Houston to the army of volunteers, but said that she has also been working to encourage other exiles to get involved and build other comanditos from the U.S.

Barreto said volunteers need the help in the face of the regime’s persecution and efforts to disrupt the opposition’s campaign, and to deal with the country’s dire economic situation.

“Our people face all sorts of difficulties, from the inability to fill their cars’ gas tanks to being able to get to places because the regime decides to erect roadblocks,” said Barreto, a college math professor before she fled the country. Venezuelans who oppose the government, she said, are “constantly watched. Their phones are tapped.”

Barreto said that she is aware of the risks that the election volunteers face, but added that Venezuelans have no option but to press ahead with trying to win the election.

“You always fear for your friends, you are always concerned about the risk that our former neighbors face.... But we must act, because this regime has already taken everything from us,” she said. “They have taken everything except our ability to hope.”