West Virginia is having a record year for tornadoes. Experts say it’s hard to pinpoint why

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

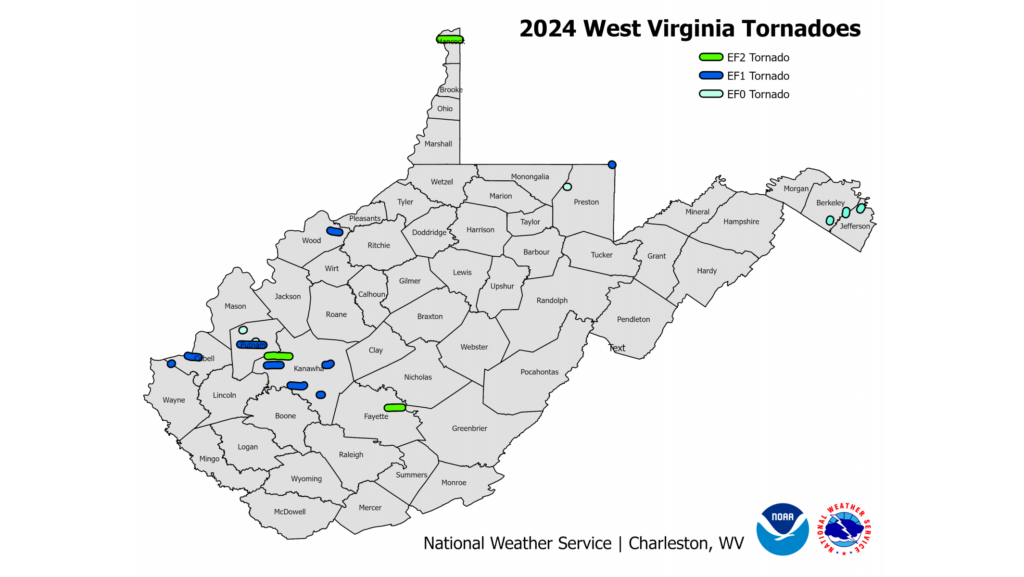

The National Weather Service in Charleston, W.Va., has recorded 18 tornadoes in West Virginia so far this year, a new state record. (National Weather Service graphic)

As tornado season winds down, West Virginia is having a record year for the storms. As of earlier this month, the National Weather Service in Charleston had recorded 18 twisters in the Mountain State so far this year, which is a new state record for the most tornadoes in a calendar year.

Until this year, the most active year for tornadoes in West Virginia was 1998, when 14 tornadoes occurred.

It’s not just West Virginia. The United States is seeing an increase in the storms this year as well.

According to preliminary numbers from the Weather Service, as of June 26, the United States had 1,262 tornadoes, compared to the average annual trend of 1,004 through this time.

“Reasons… that’s a tough thing to say,” said Harold Brooks, a senior scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Severe Storms Laboratory. “Basically, the ingredients [for tornadoes] have come together more often than they have in the past this year.”

While climate change is impacting extreme weather, increasing the frequency and intensity of heat waves, droughts, floods and wildfires, experts say connecting climate change to an increase in tornadoes isn’t as simple.

Tornadoes are “very localized events,” and the United States does not have a very long record of tornadoes to refer to, said Jana Houser, an associate professor at The Ohio State University. Houser studies radar analysis of tornado formation and the processes that impact their evolution, intensity and path.

“There’s some question about how has climate change actually modulated the larger scale pattern that could potentially make conditions over a larger geographic area favorable for tornadoes,” she said. “So you can’t pinpoint any one exact event to climate change, but at the same time, climate change is modifying the larger scale environment, so it could have made a signal just kind of like a little bit more robust than what it might have been otherwise outside climate change.”

The nation’s formal tornado database goes back to 1950, but for 20 years, from 1950 until 1970, those reports came from students in the 1970s who dug through newspaper reports for mentions of tornadoes and tallied the numbers for those storms, Houser said.

In the 1990s, the National Weather Service brought online a series of weather radars able to determine areas of storm rotation, she said.

“Prior to that point, somebody had to see the tornado, somebody had to see the damage, somebody had to call the Weather Service and report the tornado,” she said. “But with the advance of the radar system… we’ve been able to much more accurately understand the nature of tornado frequency.”

Brooks said there’s no scientific evidence that tornado activity in the United States is linked to climate change.

“A large part of that is because the U.S. is unique because our environments are so dominated by the presence of the Gulf [of Mexico] and the Rockies, and those aren’t going anywhere,” Brooks said. “…Tornadoes are pretty hard to pin down as a climate effect anyway.”

For tornadoes to develop, there needs to be a combination of lots of warm moist air at low levels and lots of cool dry air aloft. Storms also have to be organized and rotating, which require wind shear, a change in wind direction and/or speed at a height.

“[With climate change] some of the ingredients that are important for tornadoes will become more favorable, others will become less favorable,” Brooks said. “And what the balance is is really hard to tell.”

Jason Hubbart, a professor and associate dean of research and the associate director of the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, said climate change may indeed be involved in the uptick.

“With increasing temperatures and continental climate instabilities in the higher atmosphere, we may see an increased formation of high-velocity unstable winds and subsequent tornadoes in the Midwest and Appalachia,” he wrote in an email to West Virginia Watch. “Additionally, citizens and agencies are equipped with better technologies to detect and track tornadoes, so increased numbers may be detected.”

Many West Virginians may have heard the state’s hilly terrain prevents tornadoes from forming or breaks them up as they travel. But Brooks said the state’s elevation matters more than the terrain when it comes to tornadoes. The tornadoes that happen in the middle of the country are due to the presence of the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico. It takes more effort to get the moisture required for thunderstorms into West Virginia, he said.

“It’s because you’re high, not necessarily because there are hills,” he said. “If you were high and flat, it would still have trouble getting enough moisture to get storms to go.”

Since 1875, 117 West Virginians have died in tornadoes, and most of those deaths were prior to 1950. A total of 192 tornadoes have been confirmed in West Virginia since 1875, though many more have occurred than were reported, the Weather Service said.

In 1944, a tornado tore through Shinnston as well as communities in Maryland and Pennsylvania, destroying 404 homes and killing a total of 153 people, including 103 West Virginians.

According to the National Weather Service in Charleston, the state’s uptick this year may be “nothing abnormal at all.” The numbers have increased largely because weaker tornadoes are being reported.

“Due to the prevalence of security cameras, cell phones and social media, many more of these tornadoes are being recorded now than was possible in the past,” according to the Weather Service.

Drones have improved the weather service’s ability to distinguish tornado damage from straight-line wind damage, which can be challenging, the weather service said.

“This is especially true in hard to access areas or where there’s not very many damage indicators,” the Weather Service said. “Before drones became commonplace, NWS survey teams were limited to what they could see from the road since aerial reconnaissance had to be done by costly fixed-wing planes or helicopters. Drones can now give us a complete picture of the damage, even in hard to access areas, and they have allowed us to be more accurate in what we call tornado vs. straight-line wind damage.”

All of the tornadoes reported this year in West Virginia so far have been weaker, EF0, EF1 or EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale, a 0-to-5 scale gauging tornado strength based on estimated wind speeds and related damage.

Of the 18 tornadoes that have been reported in the state this year, 10 were reported on April 2, breaking the record for the number of tornadoes on one day in the state. That day, a total of 17 tornadoes were reported across the National Weather Service Charleston’s 49-county area in Ohio, Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia. In West Virginia, the tornadoes damaged or destroyed 376 homes, according to West Virginia Emergency Management.

An EF1 tornado was reported east of Parkersburg in May. Also that month, an EF2 tornado hit Hancock County, reportedly destroying homes and farmland.

Houser said reports of more intense tornados, those with EF3, EF4 and EF5 ratings, have been constant, if not decreasing. But there’s been an increase in reporting of weaker tornadoes, likely because they’re easier to report these days than they have been in the past.

“Anybody can be out there and take a picture, and have really easy access to Twitter or the National Weather Service, the local news place,” she said. “We have storm chasers out covering the country in a way that has never before happened within the last 10 years or so. So basically there are people who are going to see tornadoes, and if there’s one to see, somebody’s going to see it, and somebody’s going to report it.”

Prior to radars that can confirm rotation and cellphone pictures of funnel clouds, there were instances where tornadoes could have been identified as a wind event, she said.

“So, we’re basically surveying the atmosphere in a way that has never been done before,” Houser said.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post West Virginia is having a record year for tornadoes. Experts say it’s hard to pinpoint why appeared first on West Virginia Watch.