Why Brett Kavanaugh Shot Down a Fake Case That Would Have Blown Up the Tax Code

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court passed up an opportunity to implode the United State tax code on the basis of bogus facts. By a 7–2 vote, the court sided with the government in Moore v. U.S., a case that conservative activists engineered to preemptively kill an Elizabeth Warren–style “wealth tax.” Moore, however, does not mean that a future federal tax on exorbitant wealth will survive SCOTUS. Rather, it seems to stand for the proposition that even this very conservative court has limited patience for oligarchical policy demands dressed up in the shaggy pretext of a fake legal controversy.

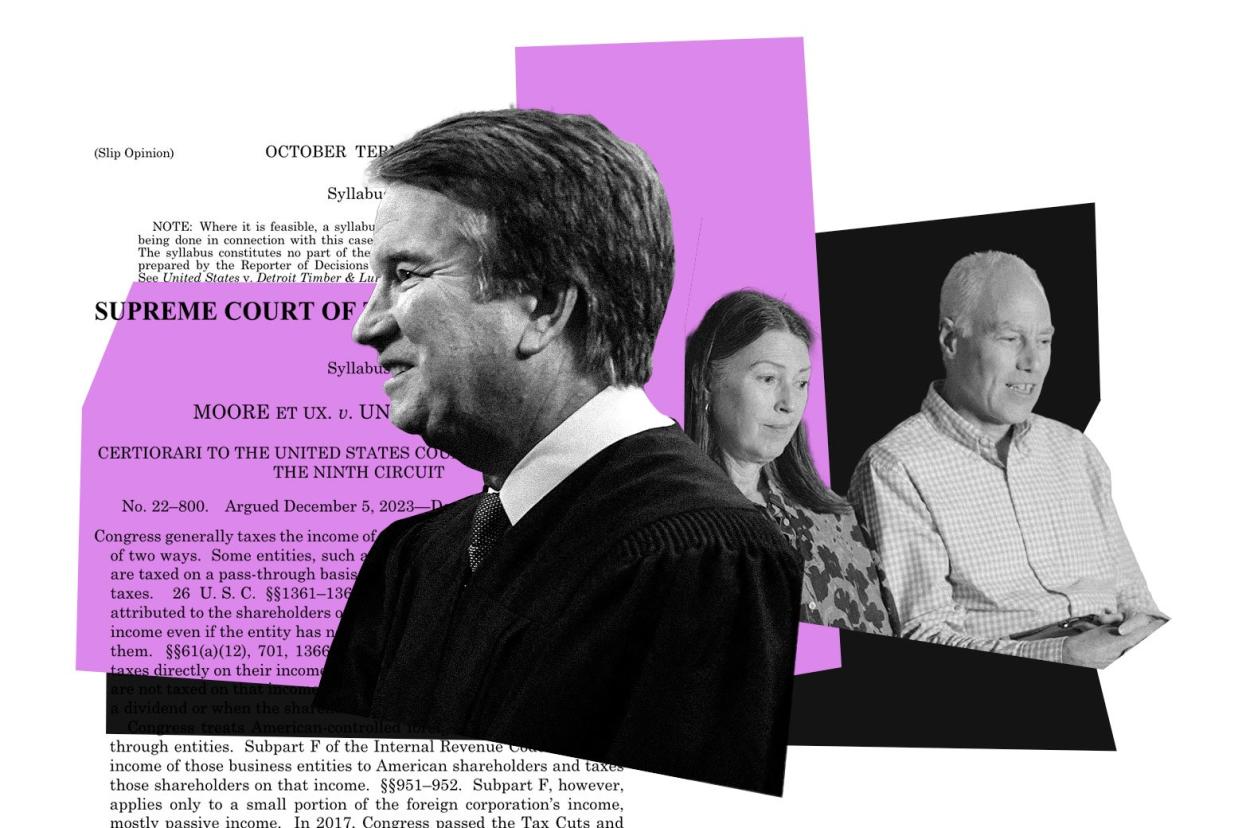

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s majority opinion in Moore recounts the facts as Charles and Kathleen Moore (the plaintiffs) and Andrew Grossman and David Rivkin (their lawyers) presented them. By this account, the Moores beneficently invested just $40,000 in KisanKraft, an American-owned corporation that manufactures farm equipment in India. They received a 13 percent ownership share but no immediate distribution of its income, even as the company made a great deal of money. So they were shocked to discover that they owed $14,729 in “income” on federal taxes after Donald Trump signed the 2017 tax cuts. It turns out that bill included a one-time, “backward-looking” tax on American shareholders of American-owned corporations located oversees that accumulated undistributed income. This provision marked an attempt to encourage Americans to reinvest that money domestically.

Rather than accept this obligation, the Moores sued the government, alleging that the new tax was unconstitutional. This theory was cooked up by BakerHostetler attorneys Grossman and Rivkin, the latter of whom is a good friend of Justice Samuel Alito. These lawyers argued that their clients were caught up in a grossly unfair scheme that penalized magnanimous Americans who tried to assist overseas corporations through investments. In this telling, the new tax punished U.S. citizens, like the Moores, who had little to no direct involvement with these companies, attributing to them a falsely heightened level of control over their operations. Grossman and Rivkin therefore claimed that the tax violated the 16th Amendment, which authorized federal “taxes on income, from whatever source derived.” They insisted that the amendment is implicitly limited to “realized” income, meaning money that’s been paid out to individuals.

There are three problems with the case, best taken in reverse order. First: The 16th Amendment does not include a “realization” requirement. Congress has taxed unrealized gains since long before the 16th Amendment was ratified, and its drafters made an affirmative choice not to impose this limitation. Second: If the plaintiffs’ theory is correct, then “vast swaths” of the modern-day tax code are unconstitutional, as Kavanaugh pointed out. Myriad corporations and partnerships are “taxed on a pass-through basis”; that means the entity’s owners, typically shareholders or partners, pay taxes rather than the entity itself. And these owners pay taxes “on the income of the entity,” Kavanaugh wrote, “even if the entity has not distributed any money or property to them.”

The Moores, he continued, “cannot meaningfully distinguish” the recent tax “from similar taxes” on corporations and partnerships. “The upshot is that the Moores’ argument, taken to its logical conclusion,” would light much of the Internal Revenue Code on fire. This arson would “deprive the U. S. Government and the American people of trillions in lost tax revenue.” It would “require Congress to either drastically cut critical national programs or significantly increase taxes on the remaining sources available to it—including, of course, on ordinary Americans.” (Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, suggested that the majority overstated these consequences, but added that “if Congress invites calamity by building the tax base on constitutional quicksand,” the courts have no “power to fashion an emergency escape.”)

Kavanaugh and his colleagues in the majority declined to take that drastic step. They avoided catastrophe by affirming that the government can attribute a corporation’s undistributed income to its shareholders, deeming it “realized” gains and taxing it. The court therefore declined to decide whether truly “unrealized” income can be taxed under the 16th Amendment. (Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, though, explained why it can be in a sharp concurrence, reminding her colleagues that the court should not override “the representatives of the people” on tax policy.)

Which brings us to the third flaw in Moore, unmentioned by the court but lurking, perhaps, in its highly skeptical analysis: The plaintiffs made up the facts of this case, stretching the truth far past its breaking point. University of Florida Law professor Mindy Herzfeld’s invaluable reporting at Tax Notes, verified by the Washington Post, points to numerous “mistakes and misstatements” in Grossman and Rivkin’s narrative. Charles Moore claims to have invested $40,000 in KisanKraft in a single transaction—but he actually invested $150,000 in three transactions over seven years. He also advanced the company $250,000 for a year, drawing 12 percent interest. Perhaps most egregiously, he served as director of the company for five years, repeatedly traveling to India and receiving at least $14,000 in reimbursements. Moore’s lawyers framed him as a passive investor who had little direct involvement with KisanKraft and merely wished to help it succeed through a relatively small investment. In reality, he was closely and continually involved, making his undistributed income exactly the kind of gains that Congress had traditionally taxed.

Over the past few years, the Supreme Court has consistently embarrassed itself by embracing fake facts to reach its desired (conservative) outcome in a number of phony cases. A victory for the Moores here would not only have destabilized much of the U.S. tax system, but also further confirmed that the justices will shamelessly exploit a counterfeit case to shift the law rightward. There are small signs that some members of the court are losing tolerance with the far-right-movement lawyers who keep lying to them. Moore offers further hope on that front. Chief Justice John Roberts joined Kavanaugh’s opinion, along with the three liberals—no surprise there. But Justice Samuel Alito joined Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s narrower (though still important) concurring opinion, despite his deep personal friendship with Rivkin. (He rejected calls to recuse from this case.) Alito sounded most enthusiastic about the plaintiffs’ theory at oral arguments. Yet not even he could sign on to their loony revision of the 16th Amendment.

Kavanaugh was careful to cabin his opinion, clarifying that the court had not passed on the constitutionality of a future wealth tax. This law, proposed by some Democrats, would tax the “net value” of rich people’s assets, including property, putting it far beyond the scope of Thursday’s decision. Nothing in Thursday’s decision greenlights this kind of law if Congress ever somehow enacted it. Instead, the court maintained the status quo, spurning a deceptive invitation to kill a popular progressive innovation before it can be born. Grossman and Rivkin’s anti-tax crusade has, for the time being, failed to make the cut of the conservative supermajority’s aggressive policy agenda.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)