How Willie Mays, and my first visit to the ballpark with my dad, changed my life | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I was with my family when I heard Willie Mays died at 93. One of my kids asked: “Who is Willie Mays?” The person who posed the question is 20 and was born 30 years after Mays retired from a celebrated baseball career that began with great fanfare in 1951.

The exploits of most famous people are often irrelevant to ensuing generations long before they die, but not Mays.

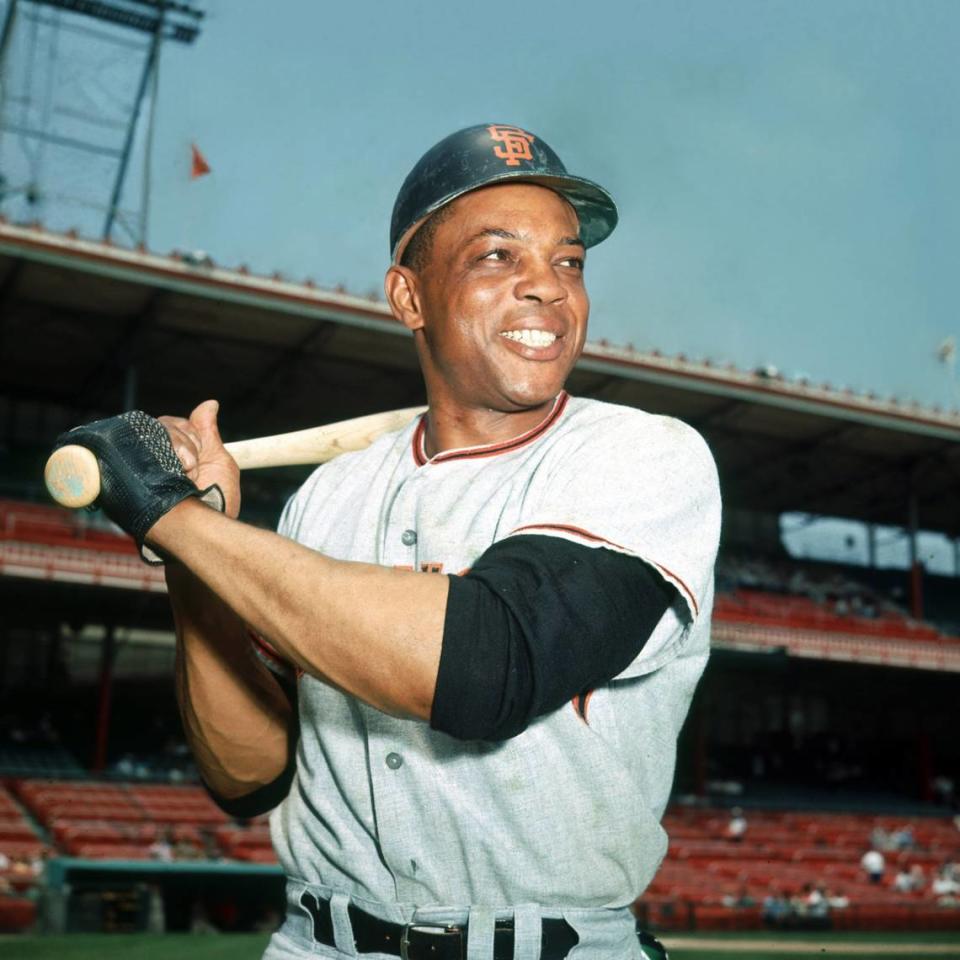

He wore the number No. 24 and for 24 years since it was christened in 2000, a statue of Mays has adorned the main entrance of Oracle Park in San Francisco, surrounded by 24 palm trees at the home of the Giants. Thousands of people have photographed themselves at the base of the statue of Mays, immortalized in an action pose, swinging the bat as Mays did brilliantly in a career that was second to no one who ever played baseball. By early Wednesday, the day after he died, the statue had become a memorial shrine to Mays.

The Oracle Park address is 24 Willie Mays Plaza. For nearly a quarter century, Mays the man and Mays the legend would often meet at the same place, where Mays was treated to adulation that grew more urgent and poignant as he grew older and frail.

Many people who cheered Mays in his final years had never seen him play live.

Opinion

But why? How could I explain to my kids — to anyone born decades after his playing days — who Willie Mays was and why he transcended a game he played with skill and style that moved people to scream themselves hoarse?

In my household, a sports answer to a Mays question is less relevant than the non-sports reasons why Willie Howard Mays Jr. stands among the most significant Americans of the last century. He was a Black man from Alabama born decades before American white people became aware of the Civil Rights movement. White America knew Willie Mays before they had heard of Martin Luther King Jr.

Mays broke in with the New York Giants in 1951 and fewer than 20 Black men were in major league baseball. The first, Jackie Robinson, is remembered for confronting mid-20th century racism in its more vulgar forms.

The truth is, all the early American and Latin American Black men playing in the big leagues day faced segregation and the dehumanization of daily taunts, slights and indignities. They absorbed it all from people who cheered them when they performed well but treated them as second-class when they weren’t playing ball.

Mays achieved acclaim denied others

From that first generation of men who integrated baseball, Mays achieved acclaim that no non-white people had before in his profession. According to the American Society of Baseball Research, Mays was the highest-paid player in his profession for a decade, quite a feat for a man whose 1960s prime coincided with the assassination of MLK and the brutalization of people marching for equality in Mays’ home state.

It’s true that Mays wasn’t political, but he was consequential. If Robinson’s bravery opened the doors of opportunity for non-white people, Mays’ excellence opened minds that were closed to the possibility that a non-white person could be great at something. Mays’ example demonstrates that greatness is possible in America when opportunity is conferred upon people from previously marginalized communities.

His example has inspired hope far beyond sports.

In 2010, in a discussion about Barack Obama, the first Black U.S. president, academic and author Eric Dyson used Willie Mays to make a larger point about how opportunities and expectations shouldn’t end with the first person to break a barrier in American culture.

“Barack Obama is the first Black president but we have to remember that. Jackie Robinson was the first,” Dyson said. “Jackie Robinson wasn’t the best ballplayer. He was the best ballplayer suited to exist under the conditions that white folk would impose upon him. I’m not suggesting that Mr. Obama is not a brilliant man.

“I love him...But at the end of the day, he’s Jackie Robinson. I’m waiting for Willie Mays to come behind him because Willie has a hell of a thing.”

Seeing Willie Mays

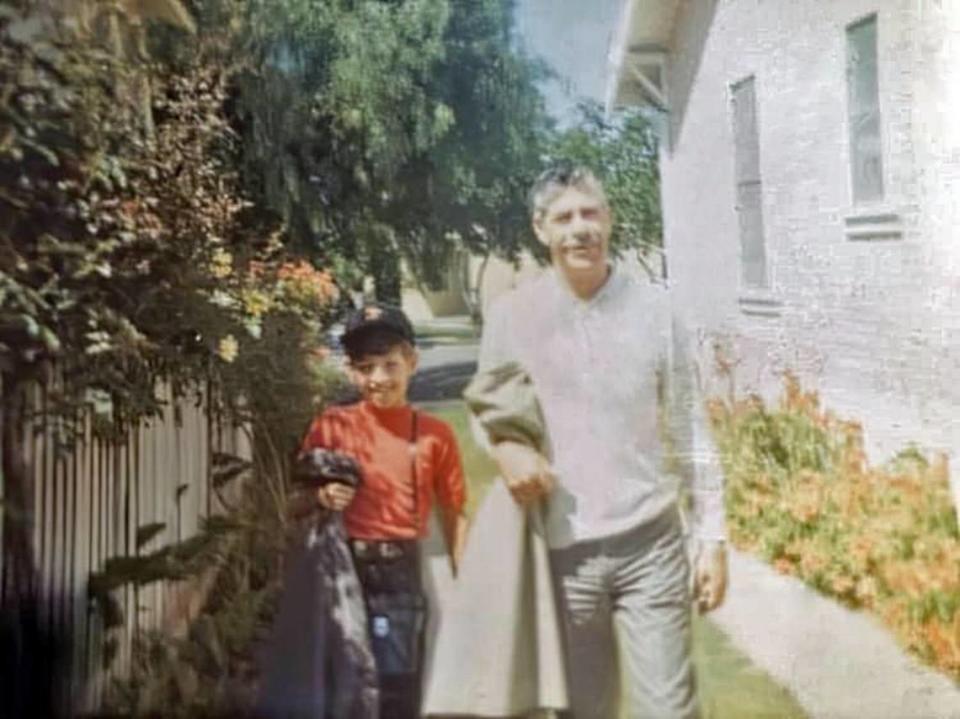

I was oblivious to who Mays was, and what he had accomplished, when my life first intersected with him on June 6, 1971. I was 8. My father, Reynaldo Breton took me to my first Giants game on a sunny Sunday. My mother, Elodia, made us pose in the driveway of our San Jose home so she could photograph a milestone in my life that has grown in significance with each passing year.

Sadly, I have no video of that day. My game program from a Giants clash against the Philadelphia Phillies is long gone. So is the Giants hat I wore, the baseball glove I took.

I only have snippets of memories jumbled together like a puzzle with too many missing pieces. I remember standing in the mezzanine at the old Candlestick Park, demolished in 2015.

I caught a glimpse of the field, then of artificial turf. The green of the synthetic grass juxtaposed with the Giants’ home white uniforms gave me goosebumps. My dad let me walk to the edge of the camera well behind home plate.

Then there he was, No. 24. All I knew was that my dad, who I revered, had told me that Mays was a great player and his word was good enough for me.

I wanted to get closer. I didn’t know I couldn’t step into the camera well, but I did anyway.

I probably sensed that I might get in trouble but I was frozen between fear and joy. Fifteen years later I would start my journalism career and, occasionally be growled at by press photographers admonishing me to get out of their way. That day was my first. I ran back to my seat, without getting in trouble the way anyone would today.

The Giants lost that game 1-0 in a brisk two hours and 27 minutes, according to the game box score. Mays failed to get a hit in three at-bats, striking out twice. My dad wanted to leave after the game.

We didn’t know when we arrived that two games were scheduled to be played. Once I knew that, I begged my dad to stay. He reluctantly agreed. I’m forever grateful.

The best there ever was

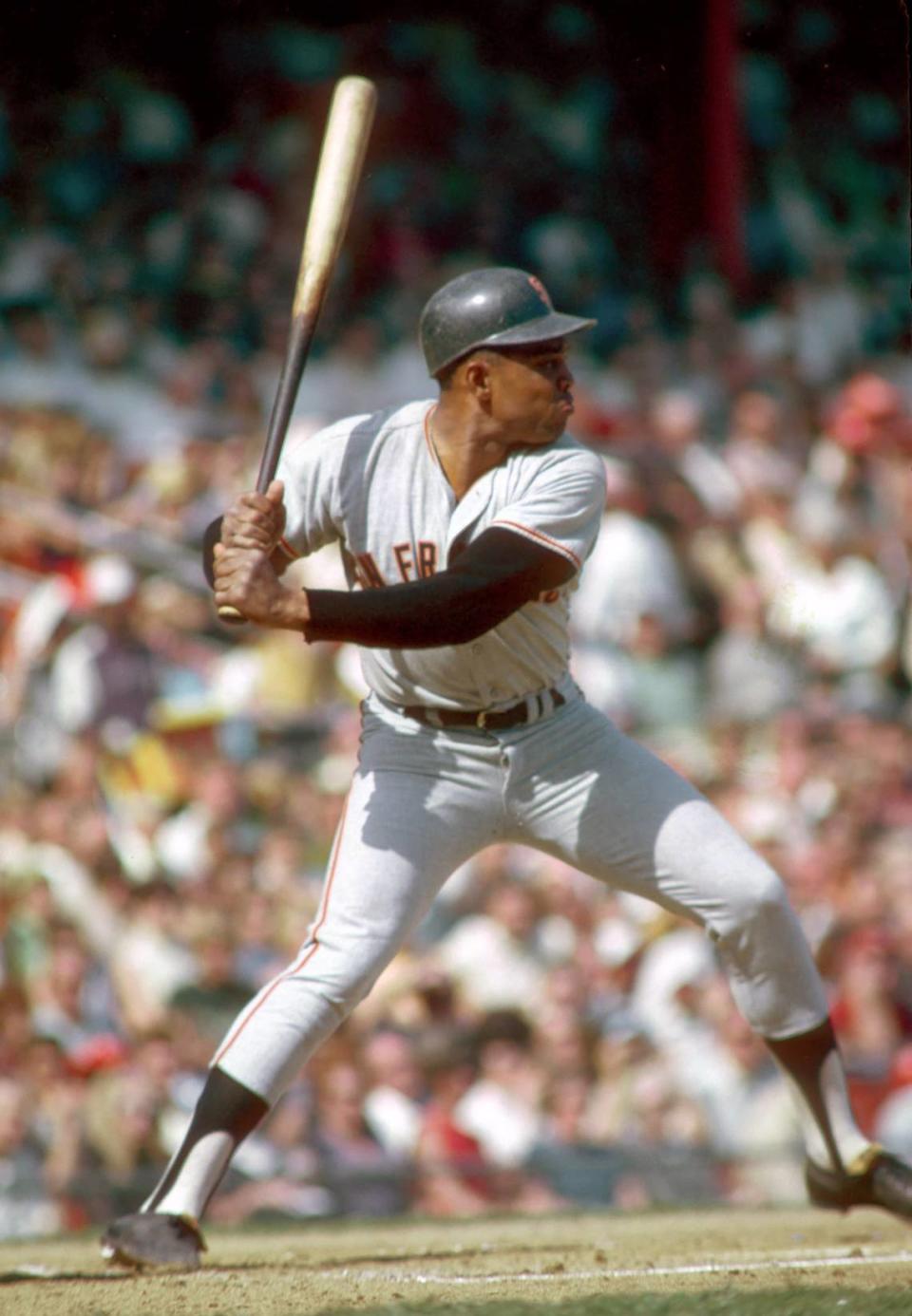

Mays was 40 by the time I saw him. Despite being beyond his prime, the respect for him within the game was so great, and his baseball intelligence was so advanced, that Mays walked 112 times in 1971 — more than any player in the National League.

His on-base percentage — which measures how often a batter reaches base — was .425, which also led the National League. OBP was not an important statistic in Mays’ day, but it is now. A .425 OBP today would be the third-best in all of baseball — hot on the heels of New York Yankees stars Juan Soto and Aaron Judge.

Again, Mays was 40.

For a long time, Babe Ruth was the most celebrated player in baseball history, despite never facing Black American or Latin American players outside of exhibitions. Ruth’s home run prowess was his calling card.

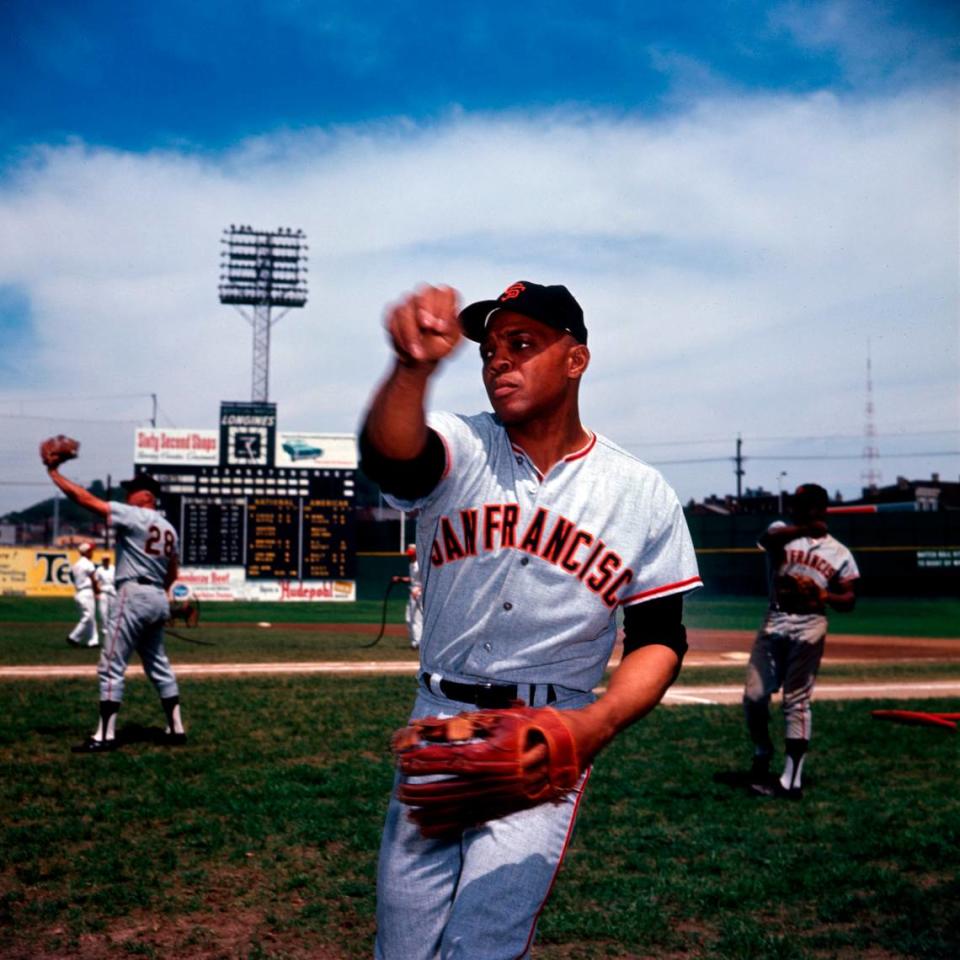

Mays could do it all. He hit home runs, stole bases and made historic catches in center field, the position requiring the most skill, speed and knowledge of the unpredictable flights of baseballs calculated instantly off the crack of the bat.

Coming along with the advent of TV, Mays was a performer who dazzled when the cameras were on. He was the perfect standard bearer when the images transitioned from black-and-white to living color.

His accolades are too lengthy to list here but accolades and awards don’t fully represent why he was great.

Mays understood that people paid their money to see him, so he approached every game intending to give each fan a memory they could take home with them.

This feeling has been diluted in the current era of baseball analytics, including on recent Giants teams that seem divorced from what the Giants have always been since they moved from New York to San Francisco with Mays in 1958.

Current Giants lose what Mays created

Since Buster Posey retired after the 2021 season, the Giants have lost what Mays created more than 60 years ago, when big-league baseball came to Northern California.

From Mays to Orlando Cepeda to Willie McCovey to Juan Marichal to Bobby Bonds to Jack Clark to Will Clark to Kevin Mitchell to Mke Krukow to Barry Bonds to Tim Lincecum to Madison Bumgarner to Posey, Giants baseball was about personalities. It was about identifiable names, and characters both homegrown and adopted.

Sometimes you wonder if the Giants ownership or the people running the Giants’ baseball operations like baseball at all.

The play of the current team is too often lifeless, filled with players who are interchangeable parts. Except for Rocklin-born pitcher Logan Webb and outfielder Heliot Ramos, it’s hard to excited about anyone wearing the Giants uniform.

Giants in Alabama

The Giants limped into a highly anticipated game Thursday at Rickwood Field, in Birmingham, Alabama, where Mays once played.

The game, at 4:15 p.m., was anticipated as a tribute to him. It’s the oldest professional ballpark in the country, the former home of the Birmingham Black Barons of the old Negro Leagues. Mays played there in 1948, when he was 17.

It was hoped that Mays could make the trip, where his life in baseball would have come full circle. Then it was clear he couldn’t make the trip for health reasons. Then Mays died late Tuesday.

The game became a memorial service. Giants announcer Dave Fleming was all of us when his voice choked with emotion as he broke the news of Mays’ passing Tuesday night.

Though he was feted and honored often, Mays still deserved more.

He came from a state in our nation bathed in the blood of slavery and defined by the oppression of Jim Crow. It was said that Mays played baseball with the joy of a child.

He was called “The Say Hey Kid,” to his dying day, a name based on the phrase “Say Hey,” which Mays once used to greet people.

These characterizations were often spoken with love and affection for a beloved man. But he was also a serious man, a proud man who lifted his profession to new heights and moved it past its segregationist past.

He was magic.

Mays walks it off

But on that day in 1971, my first trip to a big-league game, when I begged Dad to stay for the second game of a doubleheader, it seemed that Mays wouldn’t give us something to take home with us.

The Giants were shut out in the first game 1-0, and they were losing the second 2-0 until the bottom of the eighth inning.

They scored one run in the eighth, but the Phillies scored a run in the ninth to increase their lead to 3-1. My dad wanted to leave, I begged him to stay.

The Giants rallied for two runs in the bottom of the ninth, but couldn’t score the winner. That meant extra innings. Dad really wanted to go home. Again, I begged him to stay.

The 10th, 11th and 12th innings went by. Still 3-3. My dad was a lunch pail guy, he worked with his back, at a cannery. He started early in the morning. I knew this, but I couldn’t leave.

It was late afternoon, cold and sunny as Candlestick often was. Mays came up to bat with one out in the 13th.

God bless my dear, late father for taking me to the game that day, for teaching me to love baseball and for loving me enough to stay for that moment.

Willie Mays hit a home run over the left-field fence to end it. We saw 21 innings of baseball that day and Mays wasn’t a factor until the biggest moment.

I still see him running the bases in the afternoon sun. I see my dad, healthy and strong, as excited as I was. I thought of that moment on Tuesday when a colleague texted me the news that Willie Mays had died.

I could explain to my kids that I loved Willie Mays because he gave me a memory for a lifetime. That day was a gift. Willie Mays was a gift that will never die.