Words of lament and hope for Kansas as big agriculture eradicates farmland traditions

A farmer bales a crop on an irrigated field in southwest Kansas. The Ogallala Aquifer has transformed the region into an agricultural powerhouse but is quickly depleting. (Kevin Hardy/Stateline)

There’s still a lot to like about Kansas, but the relative economic security of five of its 105 counties insulates us from the small towns that epitomize America’s heartland.

I can’t help but lament the ongoing losses I see across the Sunflower State and thinking that we’re living in an artificial bubble. It’s a rarefied atmosphere in Manhattan where I live — largely disconnected from vast sections where work has disappeared, times are hard and few people live anymore. A hard truth is that our state’s plentiful grain crop has come at the expense of nearly everything else, bringing predictable cultural stresses and conflicts.

Rural and urban, we are surrounded by collapsing institutions, erosions of trust and a loss of faith in a shared sense of meaning. Motivating me to write about my home state is a mixture of awe, affection, sorrow and hope. Older Kansans especially can testify to these, although I’m aiming for the hearts of all ages.

Driving to a distant funeral the other day in a far corner of the state, I was saddened by decay and demolition everywhere. I felt the absence of people, commerce and landmarks gone missing. Railroads, homegrown manufacturing, hotels, restaurants, churches, department stores, hospitals and clinics, as well as many fine old homes, are gone. I noted this erosion as I crossed the Wheat State 20 times while Biking Across Kansas from 1985 through 2017.

None of this denies the abiding beauty, history, enterprise, colorful characters, wealth and general decency of Kansas people. There are signs of prosperity and innovation but also deterioration and despair, with meth houses in many places.

Kansas is like every other place: the big get bigger, the rich get richer. Consolidation, represented by Big Ag, appears to be an inexorable market force. I’m reminded of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child”:

“Them that’s got shall get

Them that’s not shall lose

So the Bible said

And it still is news” (based on Matthew 25:29)

The population in most of Kansas’s rural counties peaked many decades ago. Nearly all of the meager increase of humans is concentrated in Wichita, Kansas City, Topeka, Lawrence and the Manhattan-Junction City-Wamego area, where I reside. Population is also growing in the areas surrounding the state’s massive slaughterhouses, feedlots and dairies, which have built service centers, often unincorporated, around immigrant labor. But that’s nowhere near enough to stave off the decline, which is only expected to increase.

We can picture modern agriculture as an hourglass. At the top not long ago were many more farms producing commodities, which were funneled down toward the thinner waist, where a few key food processors controlled profits, which were then funneled downward to consumers in a broad variety of manufactured foods.

What’s changed is that now there are fewer but larger producers at the top of that hourglass as well as fewer but larger food processors occupying the middle. With farmers’ average age creeping upward, the looming question of who will assume stewardship of the land should be of concern to all of us.

Eastern Kansas, for example, thrived when almost every farm had a barn and silo to store homegrown grass and grain plus tractor-drawn manure spreaders to distribute animal waste onto fields, fertilizing the next crop. Farmers kept their beef calves on the farm until they were finished and ready for slaughter.

Beginning in the 1960s, concentrated animal feeding operations replaced these traditional agrarian practices, narrowing control of the market in favor of fewer but larger producers. Huge, smelly feedlots dramatically increased pollution of creeks and rivers and the air we breathe. Farmers, their numbers shrinking, had fewer buyers to choose from. The same now goes for dairying, as it already has for chickens and hogs.

Large corporate dairies — not family dairies — get the best prices and the best deals. If a dairy with 100,000 cows unintentionally sends out a tank of spoiled milk that dips below state health standards, does anyone really think their milk will get pulled out from processing plants? “Too big to fail” applies to more than banks. Every lactating cow needs 30 to 50 gallons of drinking water a day, so never mind falling water levels in the Ogallala Aquifer, or hastened climate change resulting from production of more methane from more animals.

Rapid depletion of the aquifer is an increasing threat to our economic stability, as is out migration of young people seeking employment. So too is the drought that covered nearly three-fourths of Kansas in 2022 and temperatures that have risen about 1.5 F since the beginning of the 20th century, with greater warming in the winter and spring than in the summer and fall. The number of very cold nights has been below average since 1990, while summer nights do not cool down as much.

It’s difficult to talk about Kansas without talking about wheat.

Almost 90% of Kansas’ total land area is devoted to agriculture. Most years, Kansas is the top U.S. wheat producer as well as exporter, contributing as much as 20% of the nation’s overall crop — enough to pack a freight train stretching from the state’s western border all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. It is a dark irony that, concentrating on industrial production, Kansas farmers have devalued their own goods.

Ever more sophisticated technology has led to a commodity grains glut that — thanks to the simple law of supply and demand — has crashed prices. In towns across Kansas, two- and three-year-old wheat, soybeans and sorghum commonly sit under tarps beside full-to-the-brim grain elevators. Farmers wait in the hope that prices will rise — even just a little bit — before they sell.

Farmers accepted the “get big or get out” dogma of the 1970s until their communities began to shrivel and die. Increasingly, farms of 1,000 acres are no longer enough. It’s a modern success story, yet one with a downside easy to ignore. Kansas farmers are good people, but they’ve been fed the line they must continue feeding the world. This mantra has started to smack of a con.

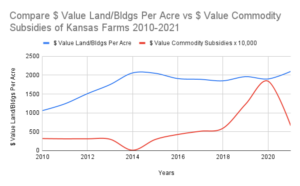

Though farm income has rebounded after falling to new lows from 2015 to 2020, income for all but the biggest operators continues trending downward. In 2020, federal commodity subsidies in Kansas totaled $1.84 billion — with 66% of those payments made to 7,842 biggest producers. They comprise 10% of recipients the guidelines were written to reward.

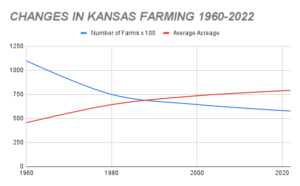

When debt-saddled farmers can’t recoup their expenses, they can quickly have no choice but to sell their land, a painful decision that sometimes means leaving rural Kansas entirely. There were 110,000 farms in Kansas in 1960 but only 75,000 by 1980. In 2022, the number of farms and ranches in Kansas was 57,700 — 900 fewer than in 2021, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. The big got bigger, the rich got richer.

Consequently, the dollar value of farmland multiplied while the number of voters shrank, diminishing the state’s representation in Congress.

Consolidation is not the only way Big Ag exacts a human cost. The very purpose of today’s highly mechanized agriculture is to eliminate people from the farming system. Modern technology — from machinery to chemical herbicides to proprietary high-yield seed — allows one farmer to accomplish a task that would have taken three a generation ago. Today, technology lies in wait allowing operators sitting at computers hundreds of miles from the farm to easily steer gigantic harvesters via satellite.

“Not long from now, the region will only need people to run the grain silos and the gas stations,” said Laszlo Kulcsar, the former director of Kansas State University’s Kansas Population Center and now interim dean of Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences. “Such people will not care about the place or the land. They will be people with no other options.”

This reflects poorly on the concept of good land stewardship — an expression of caring for our divine creation.

In Kulcsar’s view, commodity agriculture has squeezed all other economic life out of rural Kansas.

“Kansans are complacent,” he said. “They accept the depopulation. They think they are winning if they just slow it down. That’s not winning.”

Manhattan, long a city of transients, continues to produce K-State ag graduates — many of whom find work in commercial service centers owned by multinational agribusinesses. Large-scale operators hire immigrant day laborers and employ robotics, replacing family owner operators. With many purchases made from and deposits made to locations outside Kansas, local recycling of dollars is in rapid decline.

Commuters buy more online and possibly only fuel, groceries and pizza on their way home from work. Real community circles that have long generated mutual prosperity seem broken beyond repair.

The bigger picture is the steady disappearance of economic independence afforded by fewer and fewer farmers living and working their own land. It’s the relentless erosion of freedom that I mourn, and my heart breaks. But I am not alone in this lament.

Tears and grief are therapeutic. Our culture teaches us to embrace a triumphal and success-oriented posture, passing quickly into the future. But lament is needed as a ritual of cleansing and preparation for what is yet to come, and it leads to healing.

As we await next chapters, three bright hopes have emerged:

Natural Systems Agriculture is taking root at the Land Institute at Salina, where scientists influenced by geneticist Wes Jackson continue their vital research and development of perennial polyculture (such as a pasture or prairie) as an alternative to traditional monoculture of one-season (annual) crops like corn and soybeans.

Direct marketing of specialty items from small farms to consumers, plus niche products found at farmers markets, represent real potential to capture local dollars before they fly out of state.

The children of recent immigrants — a pool of highly motivated “Dreamers” seeking citizenship — could yield new entrepreneurs helping Kansas agriculture find its way forward into a more diverse future. Friction between Big Ag and emerging interests will be interesting to watch.

Wendell Berry, described by the New York Times as the “prophet of rural America,” is the author of 50 books, including “The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture.” In it, Berry argues that good farming is a cultural development and spiritual discipline. Today’s agribusiness, however, takes farming out of its cultural context and alienates families. As a result, we as a nation are becoming estranged from the land — from the intimate knowledge, love and care of it.

I’m a native of Kansas, and much of what I see brings tears to my eyes. I lament our losses and wonder how long any of us can survive this estrangement from the land that sustains us.

Dave Redmon is a retired journalist and educator reared in southeast Kansas and living in Manhattan. Through its opinion section, Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.

The post Words of lament and hope for Kansas as big agriculture eradicates farmland traditions appeared first on Kansas Reflector.