WWII veteran from Honesdale, 100, shares story as a battlefield medic in Aleutian Islands

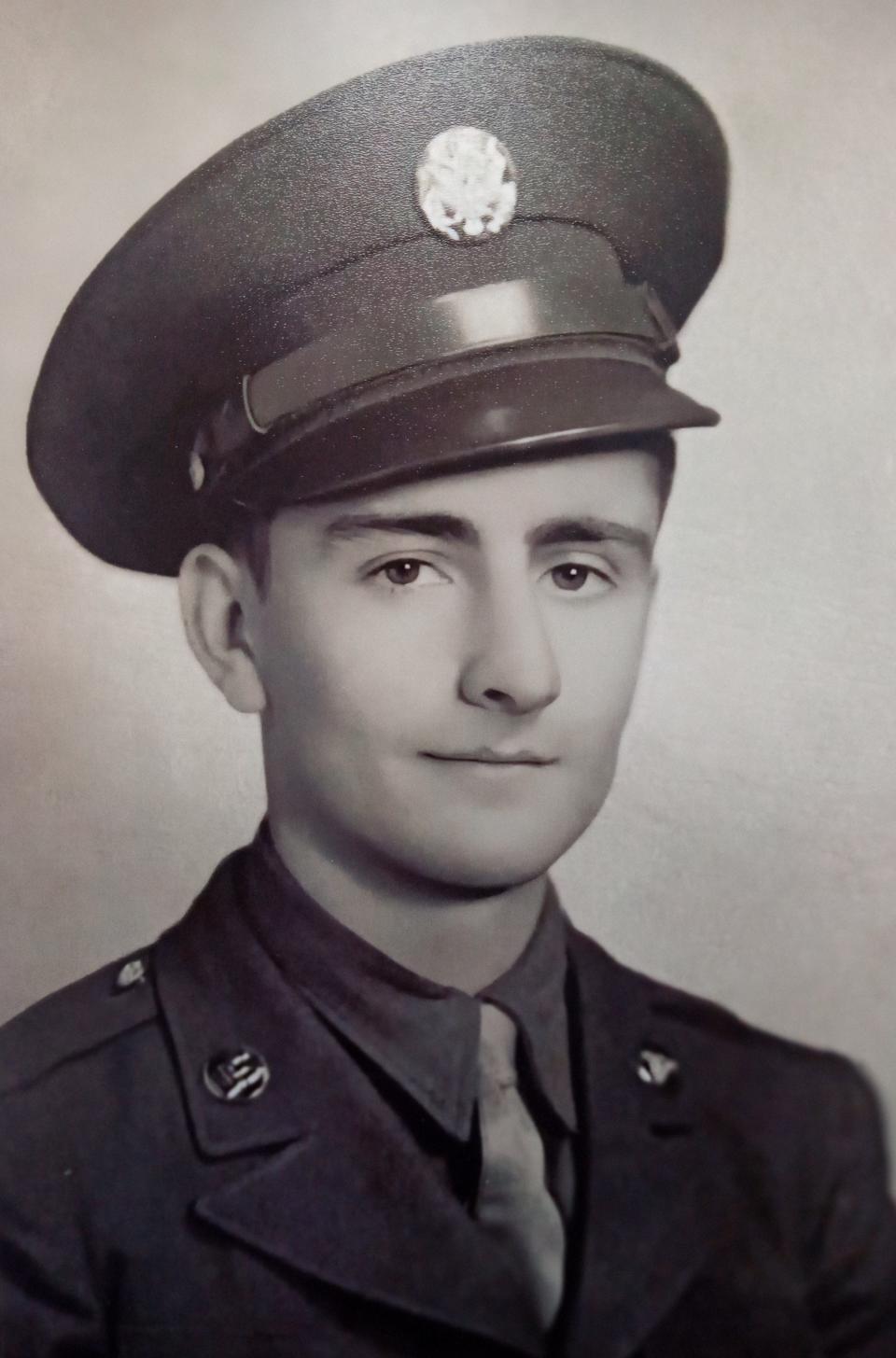

Just a few days after turning 100, Tony Battaglia shared his recollections as a U.S. Army medic serving in the embattled Aleutian Islands during World War II.

"It was a long time ago," the Honesdale resident said, freely recalling that time over 80 years past.

Pfc. Battaglia was born June 12, 1924, in Mount Vernon, New York, to Italian immigrants, Antonio and Carmella Battaglia, who didn't speak English. They raised four daughters and three sons. His brother Frank served in the U.S. Navy in the war, also making it home alive.

Battaglia was working on submarines as a welder at Electric Boat in Groton, Connecticut. He returned home and enlisted on Oct. 21, 1942, in the Army. He was 18.

He was in the 145th Infantry. He trained at Camp Grant, Illinois, for 13 weeks with the Army Medical Service. "I passed all my tests," he said.

They didn't know where they were headed next. "We were wondering when we were in the barracks, what clothes they were going to issue us," he said. "If they issued us summer clothes, we would be going to the South Pacific. We found we were going to the Aleutians. We wanted to go to the 'oven' but we went to the 'ice box.'"

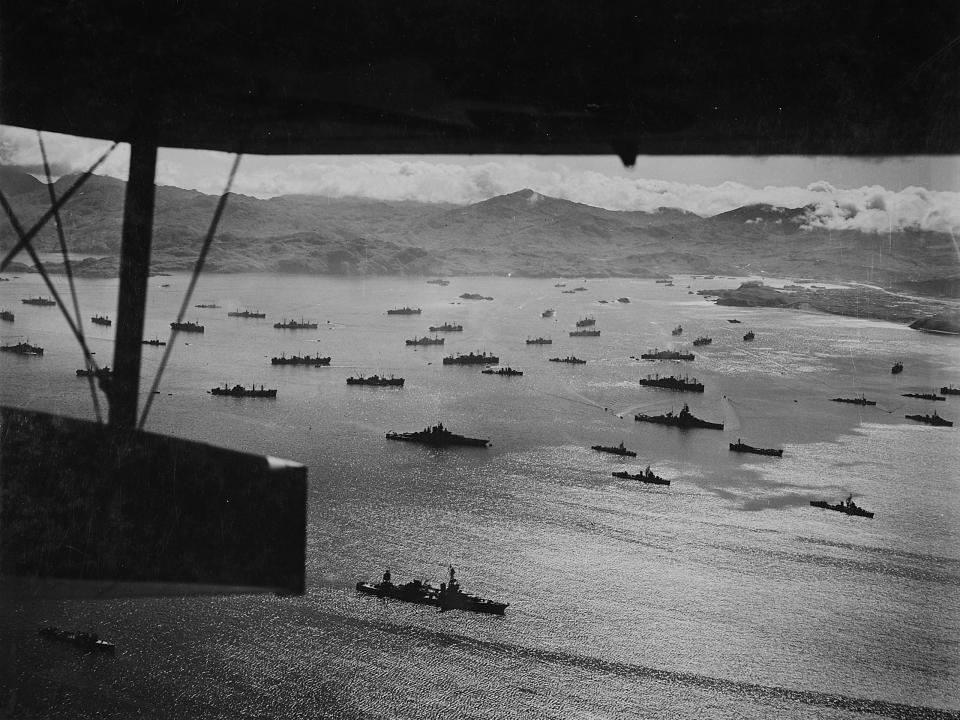

The Aleutians Campaign lasted from June 3, 1942, through Aug. 15, 1943. It was the only U.S. military campaign on North American soil during the war. Thousands of American soldiers fought against Japanese forces that had invaded the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska, which then was an American territory. The Library of Congress states that the stories from the Aleutian Campaign have largely been forgotten.

Battaglia served in Kiska and Attu islands, in the far western end of island chain.

They arrived in the thick of war when their boats landed. "When I landed there, they said my part of the island [Attu] was 80% secure... We could still hear the fighting from up in the mountains. We had the bomb squad discharging all the bombs that were left there as booby traps.”

"We had to lay down in the ditch, behind the snowbank," the veteran said. "They were shooting from the mountain. We didn't have the cannons to get them out of there, because the ship (carrying their artillery) came in too late. We landed at night, too. "It was winter... it was cold, cold, cold," he recalled.

Battaglia recalled some of the Japanese soldiers donned uniforms of American GIs their forces had killed, snuck in their camp and merged with the Japanese American soldiers at chow. "They ate their supper and took off for the hills again after supper. Eventually they got caught" when a Japanese soldier inadvertently spoke to a Japanese American soldier.

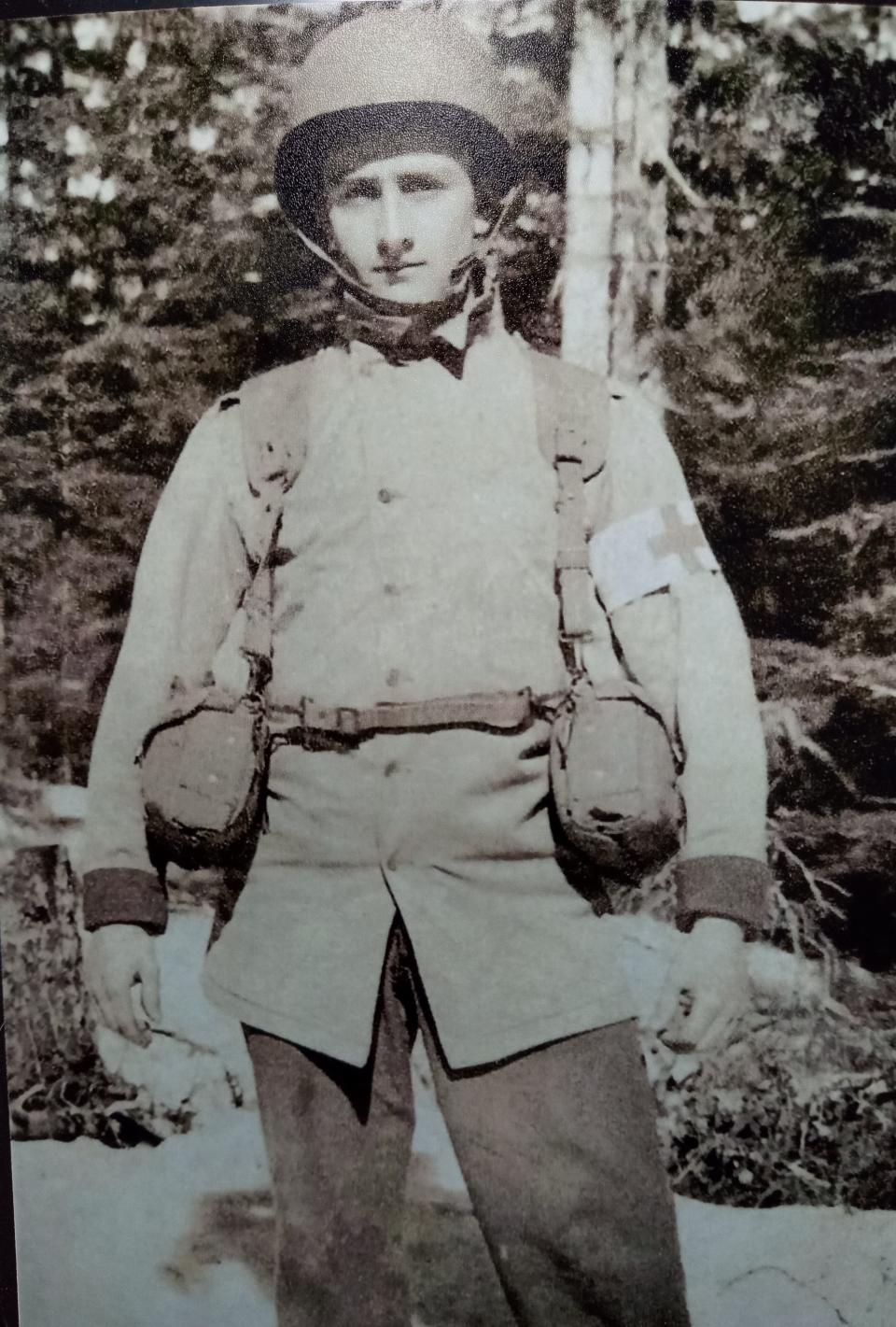

"My job was to take care of the wounded. I was a medical technician," Battaglia said. "I didn't carry a gun. I carried medical equipment on both sides. I took care of the wounded that I could." Other armed soldiers accompanied him and the other two medics. They traveled in an ambulance.

"If anybody got hurt, I was the one that had to patch them up. If anyone was hurt serious, they were shipped to Anchorage, which was not very far... it was the main hospital."

He served duty in field hospitals, giving the wounded intravenous fluid and shots.

"We came under fire all the time. The red cross on our arm [didn't mean a thing], if you were an American, boom, boom, boom," he said, making his hand like a gun as he spoke.

He said they treated the soldiers right on the battlefield. "And if the American soldier was dead, you wrapped him up in a body bag and you left him there with his dog tags on his gun, so the next group could come and take him away,” he said.

"You couldn't stay in one spot; you had to keep moving because they (the Japanese army) were all over. They had the advantage on us. They were shooting from mountains with cannons,” Battaglia continued. “We were shooting up them at the mountain. You couldn't see them unless you saw the smoke from the fire."

"Plenty of American soldiers got killed," he said. "You got hand grenades thrown at you. You got bombs falling on you. You had no protection because they had the advantage... I do remember a lot of Americans dying; I happened to be one of the lucky ones."

"A lot of memories, but I was a soldier. I lost a lot of friends," he said, including a soldier who was a neighbor from Mount Vernon who he found had been killed. After the war, Battaglia went to see his neighbor's father, who wanted to know the details of what happened.

He and other soldiers, including his neighbor, had dug under the snow and a rock ledge to sleep. The Japanese bombed them, and Battaglia was the only one who survived the attack, being protected by the crevice.

One day their ambulance hit a Japanese mine. Battaglia was injured; the aged vet rolled up his pant leg to show the scar. His face was cut from glass. Other medics rescued him.

The Japanese poisoned the farmland. He picked and ate a poisoned cucumber, making him gravely sick. He was in the hospital in Anchorage for two weeks. Ever since, he shuns cucumbers.

Afterward, he was transferred out of the "ice box" to the "oven," serving as a medic in the Philippines. The Japanese surrendered while he was there. His company found American prisoners of war in cages and liberated them.

There were happy memories too, he said. United Service Organizations (USO) shows came to Alaska with comedians and movie stars, including Bob Hope, Jerry Collona, the Marx Brothers and Jimmy Durante, who Battaglia sat next to.

He was discharged Christmas Day 1945 at Fort Dix, New Jersey. He had a big welcome when he arrived home to Mount Vernon. "My mother didn't hear from in two years. I was in a place where you couldn't get mail out right away," he said. Teary-eyed, Battaglia recalled his mother's joy when he was able to call home.

For his service, Battaglia received the American Service Medal, Asian-Pacific Service Medal, Good Conduct Medal, World War II Victory Medal and the Purple Heart.

In 1951, he and his late wife Gloria were married. He spoke of his love for his two children and grandchildren.

Battaglia worked in a factory and became a TV repairman. He also was custodian at his Catholic parish. In 1987, he and his wife moved permanently to their vacation home in Pleasant Mount, Wayne County.

Battaglia said he loves music but "not the rock and roll stuff," with soft dance and Italian music being his favorites. He also loves the Yankees.

"I never took drugs, I never drink," he said. "I take an aspirin and Gatorade. Gatorade is my drink."

Peter Becker has worked at the Tri-County Independent or its predecessor publications since 1994. Reach him at pbecker@tricountyindependent.com or 570-253-3055 ext. 1588.

This article originally appeared on Tri-County Independent: Tony Battaglia, 100, of Honesdale, shares about being WWII medic