Zoning in: What Columbus residents need to know about massive rezoning proposal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Have you been zoning in on what the city of Columbus mayor and City Council have been up to lately with major changes to the city codes that control what types of buildings can be located where?

For the past few years, city officials have worked on these zoning changes under an effort called "Zone In," meant to streamline the process of getting approval for development projects. The effort is intended to make it easier for developers by not requiring them to apply for variances — or exceptions to the rules.

Two of the most common variances routinely granted concern the height of new buildings and how much parking is required. Developers usually want to go higher than area residents desire, in order to get more tenants or buyers onto the same land. They usually also want to provide less off-street parking than the code requires. The Council routinely approves variances for projects on a case-by-case basis.

City officials say their hope is to "modernize" the code into a more lenient process that will eliminate delays, keep up with Columbus' growing population, and ease the housing shortage in the future. Buildings as high as 16 stories and with no required parking could be constructed along some major routes.

"Housing should be available to everyone in opportunity-rich neighborhoods at affordable price points — but the free market alone isn’t going to make it happen," Mayor Andrew J. Ginther said in an opinion piece in The Dispatch in December. "That’s why I’m bringing this policy forward."

"Council will vote early next year for some kind of a change," Council President Shannon Hardin told a meeting of residents and developers last September, saying he didn't want residents to feel the changes were being rushed through, and that they needed to get involved on the front end — not after changes are adopted.

Where are the proposed changes happening?

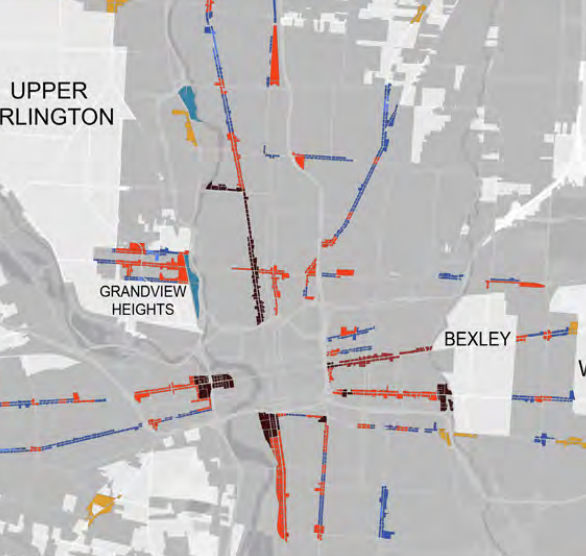

The city has targeted 12,300 parcels that follow major transportation corridors served by COTA and/or targeted for future improved "bus rapid transit" lines, under a separate new project called LinkUS.

The zoning changes shoot out from Downtown like spokes in a wheel, following main drags like High, Broad, East Long and East Main streets as well as Parsons, Mount Vernon, Cleveland, and Sullivant avenues, and other major crosstown corridors like Morse Road. Largely left off the rezoning map was Rt. 161 between I-71 east to I-270.

The city was approached by Northland area representatives about inclusion of 161 in late 2023, but staff determined that it wasn't able to add the area to the proposal due to a lack of prior analysis and public notice, said Anthony Celebrezze III, a spokesperson for the city Building and Zoning Department.

Why is this change needed now?

In November 2014, a new study made news in central Ohio by projecting large population growth. The number of people in Franklin and the six surrounding counties — Delaware, Licking, Fairfield, Pickaway, Madison and Union — was expected to rise by 500,000, to 2.3 million.

The report, called Insight 2050, was written by the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, Columbus 2020, which is an economic development non-profit created by the Columbus Partnership, ULI Columbus, a think tank supported largely by local developers, and Calthorpe Associates, an urban planning consultant.

The $700,000 effort was funded by the Federal Highway Administration, Columbus 2020, ULI Columbus, and "received support" from the L Brands Foundation, Easton Community Foundation, Casto Continental Real Estate Companies, and other local entities.

"Are today’s land use plans and development regulations aligned with the goal of attracting residents and businesses, helping communities to remain competitive and improve their tax bases?" the 2014 report asked. "Are private developers able to respond to these emerging market trends?"

In April 2019, the Insight 2050 backers released another report, this one specifically recommending that some parts of Franklin County should become more densely developed around transit. The update said central Ohio was expected to grow by 1 million residents from 2010 to 2050.

"We're going to have to look at zoning rules to ensure we have vibrant, mixed-income neighborhoods," Steve Schoeny, Mayor Andrew J. Ginther's then-development director, told The Dispatch in May 2019. "There's the opportunity to do that." Council President Hardin called current development trends "financially unsustainable."

"If we do dense development, we can reduce costs," Hardin said.

Does the proposal address redlining?

The city hired a zoning consultant, Lisa Wise, and announced in early 2021 it would launch a complete zoning overhaul. Around that same time, it launched an effort to tie the existing zoning plan to "redlining," the discriminatory practice of denying people access to credit because of where they live, pointing out that zoning played a role in who could afford to live where.

In 1935, The Federal Home Loan Bank Board asked the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, created in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression, to look at 239 cities across the country and create maps showing the level of security for real estate investments. Some neighborhoods, often with Black populations, were outlined in red and deemed the riskiest for mortgages.

The federal government drew Columbus' map in 1936.

The result was the loss of a intergenerational wealth for families of color over the years, which continued to damage vulnerable communities into the future.

Whereas that map was drawn behind closed doors, Columbus officials said this zoning effort is being done in a way to encourage full public participation.

"This increased accessibility is intended to unlock opportunities in all neighborhoods, including those that have experienced hardships from redlining and other discriminatory or exclusionary policies," reads the city's Zone In FAQ page. "Additional objectives of the update are to support investment in transit and expand the city’s housing supply. Our goal is to help create a Columbus where all neighborhoods can flourish and succeed."

Among the areas targeted for dramatic changes are inner-city neighborhoods of Franklinton, the Hilltop, the South Side, the Near East Side, Linden, and Northland. Some of the city's most affluent outlying neighborhoods, including those bordering New Albany, Hilliard, Canal Winchester and Delaware County are not recommended for any density-inducing rezoning.

Wise said in a virtual meeting that the newer parts of Columbus don't need major changes to the current land-use policies, because they have larger lots that can handle the current restrictions on setbacks and parking requirements.

Columbus City Council member Rob Dorans told The Dispatch that redlining and single-family zoning worked hand-in-hand to be exclusionary, and that Zone In's targeted corridors help fight historic redlining by slicing through many of those areas with new, more-inclusionary multi-family uses.

How would Zone In streamline development?

Zoning is basically a set of rules that places limits on developers' ability to build in ways that could impact neighboring properties. The body of code generally referred to as zoning not only separates residential areas from commercial and industrial ones, but also dictates how tall structures can be, whether sidewalks must be installed along with the structures, and how much parking they must construct, among other requirements.

When developers don't want to follow these rules, they seek a "variance" — or exception — from the City Council. This process typically begins at the neighborhood level, with area commissions, who review plans and make suggestions, often negotiate changes and ultimately render a recommendation. The city's planning staff also reviews the project and gives a recommendation, up or down.

But the buck stops with City Council, which ultimately decides what rules will be applied to any specific plan.

The entire process, start to finish, can take months, even years, and can end up derailing projects as they get re-designed to accommodate critics - the so-called NIMBYs.

So changing the rules to accommodate taller buildings, and allowing developers to determine what parking is appropriate, takes the need for variances — and neighborhood review — out of the equation. If a project meets the zoning rules, it can be built as designed, without developers seeking neighborhood or Council approval for deviations from those rules.

How does the plan affect building height?

With the exception of Downtown and certain urban corridors, Columbus' zoning code generally calls on buildings to lay low - no higher than 35 feet.

For the 12,300 parcels that will be grouped into five new "Zone In" zoning categories, the heights would grow dramatically - up to 16 stories along some major streets.

The lowest level of intensity under the new code would be called "Urban General," allowing structures of four stories. Next would be "Urban Center" and "Community Activity Center," with up to seven stories. "Regional Activity Center" calls for up to 10 stories. And the most intensive density, "Urban Core," would see the tallest buildings, up to 16 stories without a variance.

Except in the Urban General category, to get the maximum height allowed, developers would need to meet an "affordability requirement," that grants them two to four extra stories, based on the category, if developers provide the required amount of affordable housing. That means buildings of up to five stories, seven stories, and 12 stories could be built in the other four categories with no affordable housing.

Why doesn't the plan require parking?

Perhaps one of the most radical concepts of Zone In is that a developer could legally build a high-rise up to 16 stories tall that includes mixed residential and commercial and provide zero parking spaces, forcing customers or tenants who drive to park on the street or at another off-street location. That could affect the existing residents' ability to park, potentially competing against hundreds of new neighbors who need street parking.

Today, a developer of a building of five or six stories might be liable by code for providing hundreds of off-street parking spaces, often in expensive below-ground garages. Through the variance process, City Council often cuts the number substantially — but almost never down to zero for major projects.

City officials say that with the new, denser developments located along major corridors, those new buildings will be serviced by public transportation, including new "bus rapid transit" lines designed to operate like rapid transit trains, but much more cheaply.

Furthermore, officials claim that — despite there being no parking requirement — developers are still going to construct parking spaces with their new projects, because that's what renters, buyers and commercial customers will demand. This would allow developers to determine how much parking is needed without spending money on unnecessary spaces.

Where can I learn more?

The city's Zone In website provides in-depth details on the plan, including an interactive map showing every parcel affected.

What's next for Zone In?

City Council has held three public hearings on the proposal, and expects to hold a final hearing on July 17 to unveil any changes that City Council makes to the plan. Council is expected to vote on final changes before adjourning for its regular summer recess during the month of August.

After the first phase is approved, city officials have said they aim to look at updating the zoning rules for the rest of the city — although allowed uses will be far less intense in neighborhoods than they would be along major corridors. For example, it might allow the construction of duplexes or triplexes in areas that now only allow single family homes.

wbush@gannett.com

@ReporterBush

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Columbus Zone In zoning overhaul - what you need to know