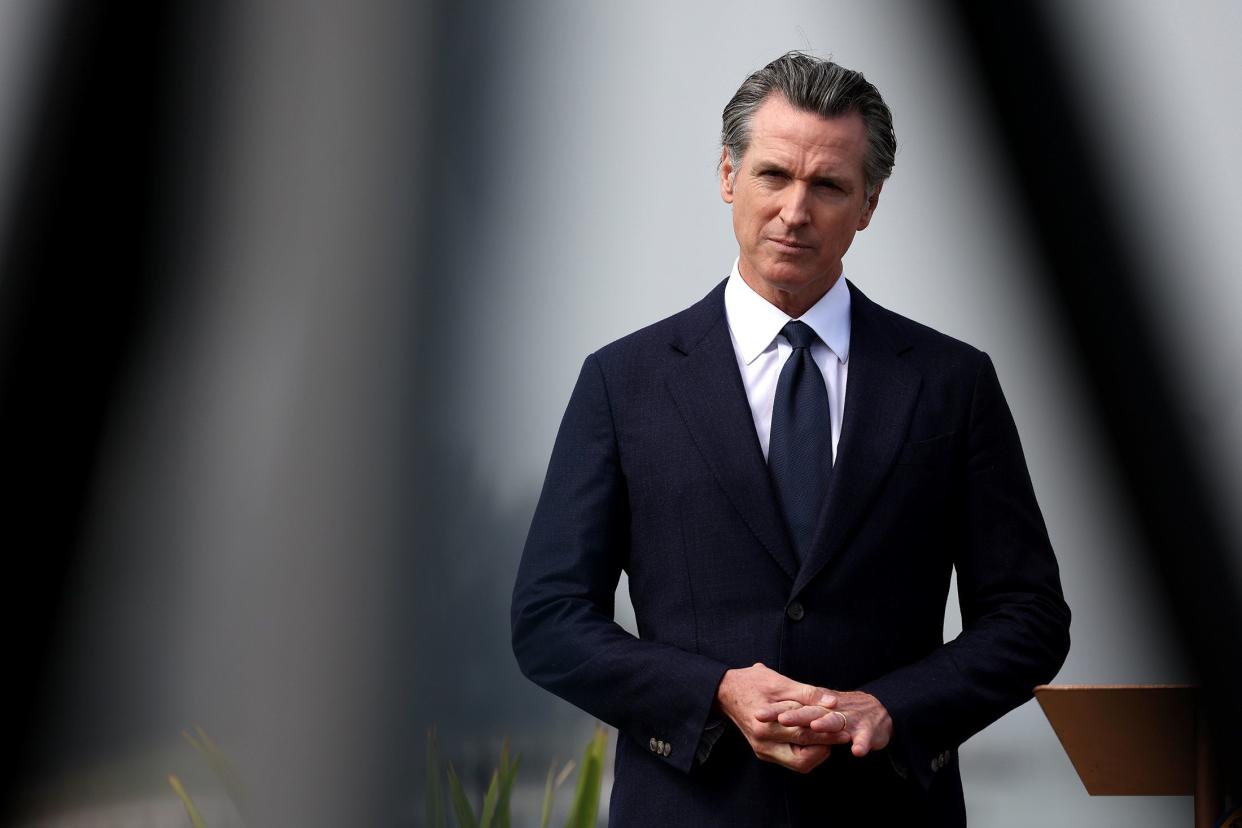

Newsom Faced ‘El Presidente’ Jabs, Now Weighs White House Bid

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- Newly re-elected California Governor Gavin Newsom has spent months deflecting speculation that he plans to run for president, saying he has “sub-zero interest” in getting into the 2024 race.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Musk Warns Twitter Bankruptcy Possible as Senior Executives Exit

Sam Bankman-Fried’s $16 Billion Fortune Is Eviscerated in Days

China Eases Quarantine, Ends Flight Bans in Covid Zero Shift

US Inflation Slows More Than Forecast, Gives Fed Downshift Room

It’s a practiced response from someone who has been tagged as a future contender for most of his life – even back to 10th grade. Newsom’s classmates had a nickname for the tall kid who was always talking about politics and world leaders: “El Presidente.”

“I would be sitting there in my little suit, obviously masking insecurity,” Newsom recalled in a series of revealing interviews he recorded in 2010 for an unpublished memoir. “I had these attention-getting devices.”

“But I was a massive nerd, loser. Strange, you know, bowl-cut haircut,” Newsom said in the transcripts, obtained by Bloomberg News. “Literally, an outcast.”

At 55, brash and telegenic, his nerd days well behind him, Newsom’s childhood insecurities from his lifelong struggle with dyslexia help to explain his visceral response to the “culture of cruelty” he sees taking hold in the Republican Party, say those close to him. Some Democrats see in Newsom the culture warrior their party needs in this moment, and maybe even a presidential candidate.

He often seems happy to oblige their interest. In his victory remarks in Sacramento Tuesday night, Newsom took aim at Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, also re-elected handily, by decrying “the zest for demonization coming from the other side, red states where there is a cruelty, talking down to people, bullying, making them feel lesser.” In a clear swipe at DeSantis, who earlier this year used state funds to fly undocumented migrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard, Newsom said, “That cruelty is embodied by flying migrants to an island, and then celebrating.”

Running for president in 2024, however, is a different matter. Current and former advisers and aides say Newsom’s decision will come down to a series of “ifs”: if President Joe Biden stands down, if his friend and ally Vice President Kamala Harris doesn’t step in, and above all, if Newsom and his wife Jennifer are willing to accept what a presidential campaign in this toxic political climate would mean for them and their four young children.

Absent all three, Newsom most likely stays on the sidelines and waits for another election cycle, these current and former advisers say, noting that he pledged without hesitation during a campaign debate to serve all four years of his second term.

Still, there could be an opening. Despite Biden’s protestations that he intends to run, an ambition he reiterated on Wednesday after the party’s better-than-expected showing in the midterms, he would be 81 on Election Day 2024. Harris has at times struggled to find her footing as vice president, causing alarm among some Democrats who see her having difficulty against DeSantis or former president Donald Trump, the two most likely Republican nominees.

The role Harris might play in Newsom’s decision is perhaps the most complicated. Close in age (Harris is 58), they share big personalities and huge ambitions, which made them occasional rivals coming up at the same time in San Francisco’s tightly-knit Democratic power structure. Newsom was the insider, a fifth-generation Californian born into a prominent San Francisco family, whose father was a well-connected state judge; Harris the outsider from Oakland and Berkeley, whose parents immigrated from India and Jamaica. They both came to prominence in 2003, when Newsom was elected mayor and Harris was elected district attorney, their early rivalry maturing into a friendship and alliance as each gained in stature and power, and their electoral paths diverged.

In 2016, Harris was elected to the US Senate seat vacated by Barbara Boxer, and Newsom was first elected governor in 2018. When he faced a recall election last year, funded by Republicans hoping to capitalize on discontent over California’s strict Covid-era restrictions, Harris flew back from Washington to campaign for him.

Newsom and Harris still share overlapping circles of friends, mentors, consultants and donors, all of those interviewed say Newsom is mindful of her support and has no appetite for challenging Harris and all the firsts she represents as a Black woman of South Asian heritage elected Vice President of the United States.

While the contingencies are sorted out, Newsom reaps free media and national attention with a stream of tweets, speeches, interviews and zingers attacking conservative GOP politicians on abortion, guns, climate policies and political extremism, frequently overshadowing Biden, as well as Harris, much to her supporters’ dismay.

In the wake of the US Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, Newsom declared California a reproductive sanctuary state, supporting a California ballot measure to establish a constitutional right to abortion that passed Tuesday, and spending his campaign cash on digital ads and billboards in Florida and Texas, inviting their residents to taste freedom in California.

On climate change, Newsom taunted Texas Governor Greg Abbott for “doubling down on stupid” for his policies protecting fossil fuels, and announced California would phase out the sale of gasoline-powered cars by 2035 on its way to achieving a carbon-neutral economy.

Should he launch a White House bid in 2024, Newsom and his political team know he must tone down the cultural rhetoric and appeal to two key constituencies Democrats are losing – White working class voters and Latinos - and he has already stepped up his rhetoric with an economic populist message designed to appeal to both.

Newsom has sought to deflect voter concerns about inflation by blaming oil companies for profiteering, a salient line of attack in California, where consumers pay the nation’s highest gasoline prices. He called a special session of the California legislature for December, challenging lawmakers to impose price-gouging penalties that will be distributed to California taxpayers.

If he is to become a viable presidential contender, Newsom is aware of how his home state and his liberal hometown are parodied, and how his pedigree makes him vulnerable. He was born into the dynastic elite of bygone San Francisco: His grandfather was best friends with former Governor Pat Brown, father of Governor Jerry Brown, who in turn appointed Newsom’s father to an influential judgeship. Newsom grew up with the city’s Democratic bigwigs coming to his birthday parties and basketball games.

As governor of a state Newsom touted on Election Night as “the world’s most diverse democracy,” he will have to answer for California’s shortcomings on his watch, including twin affordability and housing crises, plus homelessness and crime. He also faces deepening fiscal challenges in his second term, brought on by plunging payrolls, tax revenues and office-occupancy rates, and high-profile corporate defections by Elon Musk’s Tesla and others who have moved headquarters out of state.

Newsom may be helped in his political calculations by his tendency to anticipate failure, even when it is not at hand, yet to forge ahead anyway. In 2004, as mayor of San Francisco, he authorized same-sex couples to marry in violation of then-California state law, angering Democratic party elders at the time who blamed him for going too far, too fast on gay rights and jeopardizing the party’s candidates around the country.

“This is a suicidal mission,” Newsom told the interviewer of his unpublished biography, explaining why he could never succeed in a campaign for governor. “The end of the line for politicians.”

It would not be until 2015 that the US Supreme Court made marriage equality the law of the land, validating Newsom’s instincts years earlier that the law was on his side, and his ability to intuit voters’ tolerance, even hunger, for change.

For those worried about him upstaging Biden or Harris, Newsom insists his critiques should be understood as a reflection of the moral outrage the moment demands, rather than presidential ambition.

“It goes to my fundamental grievance with my damn party. We’re getting crushed on narrative,” he recently told CBS News. “We’re going to have to do better in terms of getting on the offense and stop being on the damn defense.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

One of Gaming’s Most Hated Execs Is Jumping Into the Metaverse

A Narrow GOP Majority Is Kevin McCarthy’s Dream/Nightmare Come True

Peter Thiel’s Strategy of Pushing the GOP Right Is Just Getting Started

Binance’s Thumping of FTX Shows How Centralized Crypto Can Be

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.