NFL's first Black coach Fritz Pollard hired in 1921: 'It's ironic. Not much has changed'

There was one Black head coach in the NFL in 1921 when a tiny, incredibly fast running back named Fritz Pollard was hired to coach the Akron Pros at the same time he played for the team.

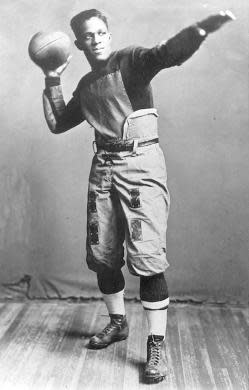

That's how good the 5-9 Pollard was. He was so swift and agile that even those who scoffed -- and worse -- at a Black player, couldn't help but cheer when he ran for three 50-yard touchdowns in one game.

Newspaper articles at the time, who described Pollard as a "colored" coach, praised his stellar football IQ.

Pollard played and coached at a time when restaurants wouldn't serve him and hotels shunned him. He played and coached when, despite being the highest paid player in the league — $1,500 a game — he wasn't allowed to dress with his team.

Doyel: 100 years ago, the NFL took its first baby steps in Indiana

Pollard, one of two Black players in the NFL and the first Black coach, would suit up in his car outside the football field or go to a nearby cigar store where the owner let him use a back room.

"Why?" said his grandson Dr. Stephen Towns, a dentist in Indianapolis. "Because they didn't want him in the locker room."

Growing up, Towns said his grandfather didn't complain or talk much about those trials. "You just lived with it. That's just the way the times were back then," Pollard would say.

But the times changed.

Black players began dominating the NFL. They dressed in locker rooms, ate with teammates at restaurants, slept in team hotels and became multi-million-dollar superstars.

The times changed, but one thing didn't.

There was one Black head coach in the NFL in 1921. There are two Black head coaches in the NFL in 2022.

"It's terribly ironic that we live in a time that Fritz Pollard's own coaching experience in the NFL isn't really that different from today," said Aron Solomon, chief legal analyst with Today's Esquire, which provides comprehensive legal analysis on news stories of the day. "The NFL has one fundamental belief about Black coaches. They believe that Black head coaches are not fit to be leaders of men."

500 head NFL coaches, 24 Black

Pollard waited his entire life for a second Black person to be named head coach of an NFL team. He didn't get to see it.

When Pollard died in 1986, after careers with a talent agency, tax consulting and film and music production, his obituary noted he was still the league's only head Black coach.

He had waited 65 years from his hiring as an NFL coach to see if he had pioneered a change.

"Oh yes," said Towns. "He wanted to see another...he wanted to see many African American coaches."

Three years after Pollard's death, Art Shell was hired as head coach of the Raiders, the first Black head NFL coach of the modern era.

But the hiring didn't break down barriers. Not the way Solomon believes Pollard might have expected.

"If somebody were to ask Fritz Pollard, 'What do you think 100 years from now it's going to be like in the National Football League?'" Solomon said.

Knowing that the NFL would be one of the biggest businesses in the nation and that 70% of the players on 32 teams would be Black?

"What Pollard would have said is that at least 70% of coaches would be Black," Solomon said. "And it's not even close."

There have been 500 head coaches in the NFL's history — 24 of them have been Black. That's 4.8%. In 2022, with the Steelers' Mike Tomlin and recently-named Texans head coach Lovie Smith, that percentage is 6.3%. Thirty percent of assistant NFL coaches are Black.

The NFL did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Racial disparity in the league's coaching ranks was brought to the forefront last week when former Miami Dolphins coach Brian Flores filed a proposed class-action lawsuit against the NFL and three of its teams, alleging racial discrimination in hiring practices.

Flores’ suit came after the New York Giants hired Brian Daboll over him as head coach.

"God had gifted me with a special talent to coach the game of football, but the need for change is bigger than my person goals," Flores said in a statement. "In making the decision to file the (complaint), I understand that I may be risking coaching the game that I love and that has done so much for my family and me. My sincere hope is that by standing up against systemic racism in the NFL, others will join me to ensure that positive change is made for generations to come."

'I'd look at them and grin'

Pollard wanted the same thing. He wanted the trails he blazed to change the future of the NFL.

And, his grandson said, 100 years after Pollard coached in the NFL and 36 years after his death, he is sure Pollard would have wanted more from the league he helped build.

When Pollard played, the NFL was new, rough and tumble, a backyard type of experiment, said Towns.

Pollard's magic on the field created a following for the NFL. Fans started showing up to see what this football league was all about.

"He literally kept the NFL from folding," Towns said. Many credit Pollard and Jim Thorpe with saving the fledgling league as it struggled to compete with baseball and boxing.

Still, some players didn't like that Pollard was playing and they despised even more that he was a star player in the NFL. Pollard was illegally hit during games and, if he landed on the ground, white players would pile on top of him and beat him, according to newspaper accounts.

"Fritz Pollard‘s skin is black. He is the son of a despised race. Bleacher crowds and outside towns jeer him and taunt him about his color," read an article in the Akron Evening Times December 5, 1920. "Opposing players make it a point of pride to rough him as much as possible. If he is tackled, as many as possible pile on him. If someone can slug him without the referee seeing him, it is done. Against all these handicaps, Fritz Pollard plays with dauntless spirit. He is one of the great football stars of all time."

As he faced criticism and discrimination, Pollard didn't fight back, not off the field. Instead, he let his play speak for itself. He was almost always in the game -- as quarterback, running back and often doing punt returns and kickoff returns. At one game, a competitor started mocking Pollard's curly hair.

"I’d look at them and grin," Pollard said in a 1974 interview with NFL Films. "(I) didn’t get mad and want to fight them. (I'd) just look at them and grin, and the next minute run 80 yards for a touchdown."

Incredible display of solidarity

Frederick Douglass "Fritz" Pollard was born Jan. 27, 1894. He attended Albert G. Lane Manual Training High School in Chicago where he played football, baseball and ran track.

Pollard played short stints of football for Northwestern, Harvard and Dartmouth before receiving a scholarship from the Rockefeller family to attend Brown University in 1915.

Pollard was wickedly smart and, while playing halfback at Brown as the school's first Black player, he majored in chemistry, earning almost all As.

All the while, he faced death threats from students and opposing teams. Pollard often had to be escorted onto the field by police officers. As he walked on, he would hear taunts shouted from the stands.

One opposing school's fans would sing "Bye Bye Blackbird" when his grandfather came on the field, Towns said.

Yet, through it all, Pollard held his head high and helped lead Brown to the Rose Bowl against Washington State in 1916.

It's a game that almost didn't happen. When the team went to sign in at the hotel, the front desk refused Pollard. His teammates took a stand. If Pollard wasn't allowed to stay at the hotel, they would all leave and head back to Rhode Island.

It was an incredible display of solidarity.

While Brown lost the Rose Bowl 14-0 to Washington State, it was a historic game. Pollard became the first Black man to play in the Rose Bowl. He also went on to become the second Black player named to Walter Camp's All-American team.

It was only the beginning of Pollard breaking down racial barriers.

'The athlete hero of his race'

After leaving Brown, Pollard pursued a degree in dentistry at the University of Pennsylvania for two years. He also worked as director of an army YMCA and coached football at Lincoln University.

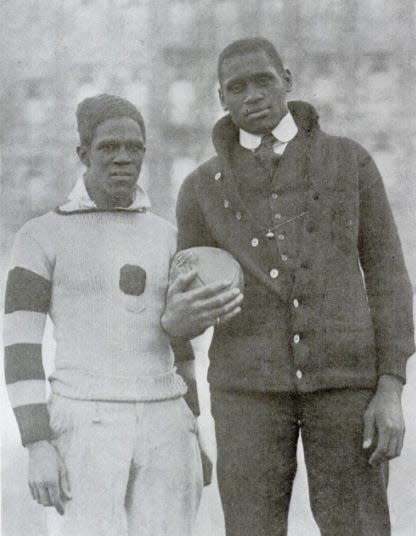

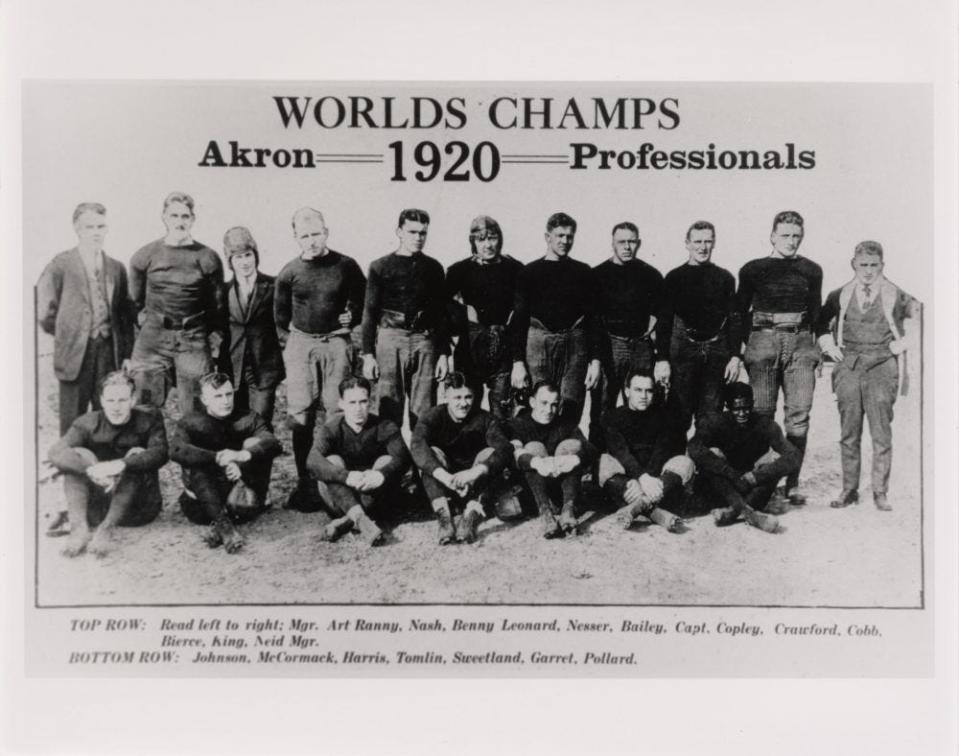

In 1919, he signed on to play for the Akron Pros in the American Professional Football Association, which was renamed the NFL in 1922.

In 1920, with Pollard leading the team, the Pros went undefeated (8-0-3) to win the league's first championship. The next year, he was named co-head coach as he continued to play for the Pros.

His white teammates had high respect for Pollard and often stuck up for him as he faced discrimination.

"Members of the Akron Pros swear by Pollard," wrote Jack Gibbons of The Akron Beacon Journal on Nov. 30, 1920. Gibbons went on to describe an incident that happened at an Akron restaurant as Pollard sat with a group of teammates.

"The waiter took everybody's order but Pollard's. He didn't care to serve Fritz," Gibbons wrote. "(Two teammates) watched the proceedings as long as they could. Then they leapt from their chairs, grabbed the waiter and proceeded to artistically maul him until he consented to wait on Pollard. And believe us, Fritz got some service after that."

Days later, Pollard played in a benefit game in Pittsburgh and was greeted with a hero's welcome.

His Black fans "were so wild over having him in their midst that they arranged a parade and met him at the railroad depot," wrote Gibbons. "Pollard has grown to such heights of fame that today he is the athlete hero of his race."

Yet, Pollard's humble, quiet ways never changed.

"He detests crowds and avoids the spotlight whenever possible," Gibbons wrote. "Fans have, perhaps, noticed that after staging one of his brilliant runs for a touchdown he seeks a place of seclusion sometimes even going so far to duck underneath the stands."

Pollard wouldn't have to dodge the spotlight for long.

After going on to play and coach for four different NFL teams in Indiana and Milwaukee, Pollard was banned from the league in 1926 along with eight or nine other Black players "in a fateful decision to segregate," according to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The ban was made official in 1934 at the height of the Great Depression when NFL team owners agreed to forbid any Black players in the league.

"They said no African Americans, period, because it was bad for business," said Towns. "It was bad for white people to come and watch Black people who have jobs."

That ban lasted until 1946.

'All of us got played by the NFL'

Pollard took the matter into his own hands and created an all-Black football team, the Chicago Black Hawks, in 1928, challenging NFL teams to exhibition games. Pollard's team won most of those games, said Towns.

He retired from football in 1937 to pursue a career in business and watched as the NFL ban on Black players started to lift after World War II. But not all teams were integrated until Bobby Mitchell joined the Washington (Commanders) in 1962.

From there, Black players joined the league and began dominating on the field. The same didn't happen in the coaching ranks.

In 2003, in response to criticism over the lack of Black coaches in the league, the NFL created the Rooney Rule, a policy that requires teams to interview at least one ethnic-minority candidate for vacant head coaching jobs.

The rule is named for former Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney, who chaired the league's diversity committee.

The Rooney Rule, however, doesn't require hiring of Black coaches, only interviewing them, said Solomon.

"All of us got played by the NFL," he said. "We thought that meant the NFL was out to hire more Black head coaches. Instead, it's a box-checking exercise. It doesn't force any team to hire a Black head coach."

Tony Dungy, who became the first Black coach to win a Super Bowl with the Indianapolis Colts in 2006, said this month the Flores suit might be "just the tip of the iceberg."

In February 2021, Dungy wrote an open letter to NFL owners about the league's lack of minority hires. Since that letter, Dungy says "not a lot has changed."

"Look at the c-suites of your teams, the medical staffs, and the ultimate decision makers — the head coaches and GMs — and you’ll see those faces don’t represent what your teams look like," Dungy wrote last year. "And it has been discouraging to see that in the last three hiring cycles of head coaches, things have not been much different. Are we to believe that you’re really doing exhaustive searches, trying to uncover the best coaches, but only two out of the last 20 have been African Americans?"

Things have not been much different in 100 years, said Solomon.

"The big contrast now is absolutely how crazy big the NFL is as a business, billions and billions of dollars," he said. "And the other big difference is that 70% of the players are Black."

Yet, Solomon said, Black men still aren't given equal opportunity to coach the teams they, perhaps, played for.

"If you think about everything Pollard fought for, this is the same thing we are fighting today," he said. "The narrative we are dealing with here is very close to the narrative Fritz Pollard dealt with 100 years ago."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: NFL's first Black coach Fritz Pollard faced racial discrimination