NH bill could pave way robust drug-testing system: How it works

Almost everything New Hampshire knows about the contents of its illicit drug supply comes from overdose death toxicology results or drug chemistry analysis in criminal cases. The state doesn’t have any comprehensive drug-testing infrastructure that alerts to real-time public health and safety concerns.

That’s because, political will aside, state statute doesn’t allow it. House lawmakers are currently revisiting a stalled bill that might cut away the red tape.

Unanimously retained last legislative session in the House Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee, lawmakers wanted more time to flesh out House Bill 470 before possibly reintroducing it in 2024.

They instead moved forward with House Bill 287, which decriminalized fentanyl and xylazine test strips and was ultimately signed into law by Gov. Chris Sununu in August. Prior, testing strips were legal only for registered participants of harm-reduction programs. Anyone else found with them faced a potential misdemeanor.

HB 470, sponsored by Rep. David Meuse, a Democrat from Portsmouth, went further than HB 287. It seeks to remove “drug-checking equipment” entirely from the state’s definition of drug paraphernalia. That includes much more than test strips, the bill indicates. It lists reagents, spectrometers, and equipment that uses high-performance liquid or gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques.

While the definition of drug-checking equipment doesn’t include the substances being analyzed, the bill seeks to shield people from criminal prosecution if they have a “nominal amount” of drugs while in the process of using or accessing checking equipment.

The equipment and results could not be used against any person engaging in the act lawfully, the bill states, meaning they’d be safe from arrest, prosecution, revocation of probation or parole, or other civil, disciplinary, or administrative actions.

How states like Massachusetts test drug supply

Lauren McGinley, executive director of the New Hampshire Harm Reduction Coalition, previously testified that HB 470 would allow the state to create a robust drug-testing system like its neighbor Massachusetts.

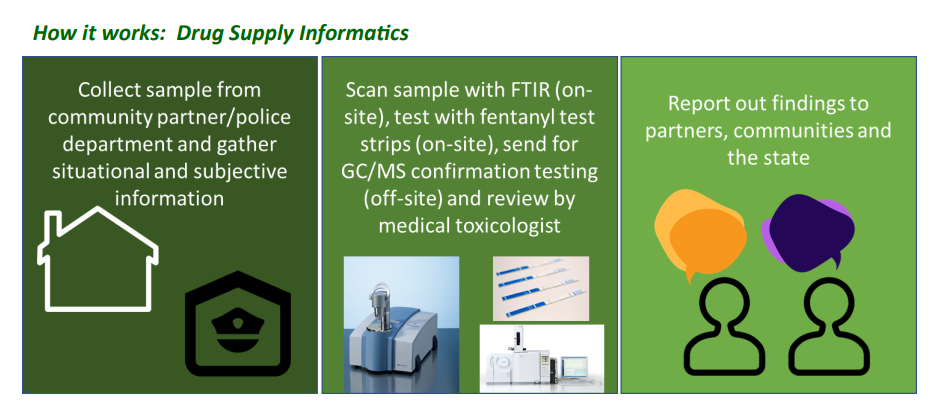

A collaboration between Brandeis University, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and various town police departments and local community partners, the Massachusetts Drug Supply Data Stream fills a gap in public health surveillance by testing local illicit drug supply to better inform public health and safety responses.

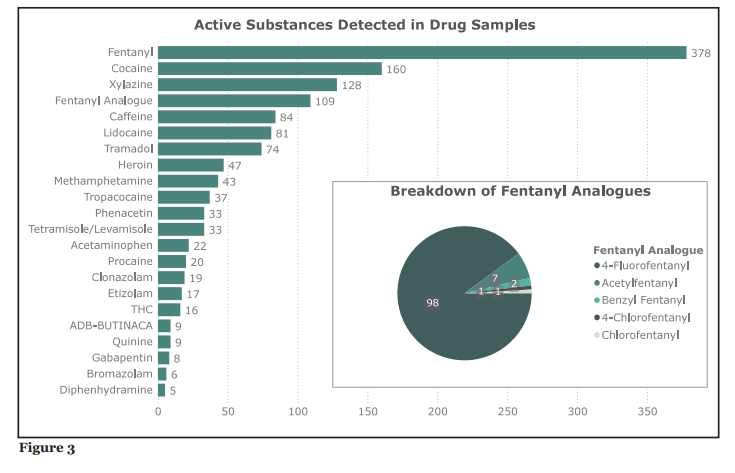

In 2021, the Massachusetts system tested 708 drug samples. Results unsurprisingly showed fentanyl was by far the most common active substance detected, and also that it was found in cocaine, heroin, and counterfeit pills. The testing detected the veterinary sedative xylazine before it started showing up in the drug supply in New Hampshire, where officials didn’t start publicly messaging about it until 2023.

The program identifies active “cuts,” or additives to the primary drugs, such as caffeine, phenacetin, tetramisole, and others. It also specifies fentanyl analogues, which are alterations of fentanyl.

Results are broken down by the program’s 11 locations around the state. In the city of Lawrence, for example, the testing site closest to New Hampshire, the main drug compounds detected in samples were fentanyl (89.7 percent), cocaine (37.9 percent), xylazine (31 percent), and lidocaine (20.7 percent).

Plain-language summaries of community drug-checking alerts and other information are offered in Spanish, Portuguese, Haitain Creole, Vietnamese, Khmer, and Twi.

Currently, the New Hampshire Drug Monitoring Initiative compiles data from various sources – such as public health, law enforcement, and EMS – to provide monthly reports for stakeholders with figures on mainly overdose deaths, calls for service, and emergency room visits.

The State Police Forensic Laboratory does analyze drug chemistry in criminal cases, but supporters of HB 470 see the bill as paving the way for a more robust system, one that isn’t limited to drugs seized by law enforcement.

Harm reduction or enabling?

Starting last legislative session, Republicans and law enforcement expressed concerns about the potential that drug traffickers would take advantage of language included in HB 470. There’s also a feeling among some that the bill tilts more toward enabling drug users, rather than offering harm-reduction tools.

And what a “nominal amount” of drugs is has yet to be defined. Lawmakers have floated 10 milligrams – the size of Abraham Lincoln’s head on a penny. Bedford Police Chief John J. Bryfonski, president of the New Hampshire Association of Chiefs of Police, previously testified that two milligrams of fentanyl can kill someone.

At a Monday work session for a subcommittee tasked with looking at HB 470, Rep. Jodi Newell, a Keene Democrat, said HB 470 would give state officials, law enforcement, and community partners more accurate information about “what’s on our streets.”

“What this does is it empowers us as a community to better target and better address the things that are creeping into our illicit drug supply,” she said.

Republican Rep. Karen Reid, of Deering, came out strongly against certain portions of the bill, including the “nominal amount” of drugs. She declared early on in the discussion that she’d be voting “inexpedient to legislate,” but ultimately softened her stance.

“What we’re saying is people can walk around with illegal substances of less than 10 milligrams and we can no longer consider those previous-stated paraphernalia as paraphernalia,” Reid said. “I do not see that as a harm reduction tool. I see that as enabling and very broad.”

Reid said the bill needed to be looked at realistically, and not through “rose-colored glasses.”

Newell disagreed with Reid’s characterization of her support for the bill, telling fellow lawmakers that her former fiancé and father of her two children died of an overdose. He overdosed in their bathroom, she said, as her 1-year-old knocked on the door saying “Dada.”

Referencing a harm reduction approach, Durham Democrat Rep. Loren Selig said recovery isn’t possible if someone doesn’t live to see the next day.

“What I see in this is, if we can keep someone who has an addiction issue alive one more day, maybe that’s the day they realize, ‘OK, it’s time for me to get help.’ Maybe it’s not,” Selig said. “Maybe it’s going to take them 15 more of those days. Maybe it’s going to take them 40 doses of Narcan before they realize. Maybe it’s gonna take them when they don’t even have enough space in their neck to inject into because they’ve run out of everywhere else before they realize that they’ve got nothing left. But giving someone that one more day also gives them that one more chance, and to me, that outweighs everything.”

As a retired law enforcement officer, Pelham Rep. Jeffrey Tenczar, a Republican and chair of the subcommittee, said he was concerned about language in the bill that might give a “work around” or defense argument for drug traffickers. He sought to take out mentions of “preparing, packaging, and repackaging.”

Lawmakers agreed on amending the bill to reflect that any packaging present must be connected to the “nominal amount” of drugs being tested. After ironing out a final amendment at a future meeting, the subcommittee will vote to either recommend or not recommend HB 470 to the full House Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee.

This story was originally published by New Hampshire Bulletin

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: NH bill could pave way robust drug-testing system: How it works