NH Dept. of Education pressure on Dover schools over books raises alarm

The New Hampshire Department of Education is heightening its scrutiny of books in libraries and classrooms, as schools continue to face pressure to remove titles that have LGBTQ+ characters or deal with mature or difficult sexual themes.

Since last year, according to public records and interviews with school officials involved, Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut and his deputies have repeatedly pressed the Dover School District to explain its decision making around library content, after raising concerns about two specific titles — one of which, according to the district, wasn’t on its shelves. Last month, records show, the commissioner also asked for an inquiry into a complaint he received about a poster on a middle school teacher’s door that encouraged people to “Read Banned Books.”

Within the past few months, state education officials have also advised schools that they need to give parents or guardians advance notice of any “course material related to human sexuality,” including English and social studies curriculum. That move raised alarms among some civil liberties advocates, who say the parental notification law was originally designed to apply to health or sex education lessons.

Taken together, these efforts represent an unusually hands-on approach by state education officials to address specific content and book concerns, as state law largely leaves it up to local school boards to decide what books and curriculum are appropriate for their district. It also comes as local schools and lawmakers grapple with competing views on how to approach concerns about curriculum and library material.

Through a spokesperson, the education department said it is not trying to force the removal of specific material and its goal was more effective communication with families and students. But its response to certain complaints — particularly regarding books that address sexuality and LGBTQ issues — have put it at odds with school officials, teachers and civil rights groups, who argue that the commissioner is meddling in matters beyond his authority.

“Any suggestion that books be banned frays the bonds of trust and cooperation among parents, schools, and students,” lawyers from the ACLU of New Hampshire and GLAD, a LGBTQ advocacy group, wrote to the Department of Education this week. “They track politicized and partisan narratives in the larger culture, and regularly target books that discuss or depict the experiences and history of members of LGBTQ+ communities and/or communities of color.”

Concerns in Dover

Dover Superintendent William Harbron said Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut first contacted him about specific book titles last fall. According to Harbron, the commissioner called to relay concerns he heard from at least one Dover resident about various books, and to ask what was being done about it. Harbon said, to his recollection, Edelblut didn’t specifically ask for the books to be removed but did make clear that he was concerned about them.

That was the last phone conversation Harbon recalled having with Edelblut, and administrators thought the matter was resolved for the time being.

But a few months later, in March of this year, state education officials reached out again with questions about "Boy Toy," a novel about a teenage boy who is groomed and sexually assaulted by his middle school teacher. According to emails obtained by NHPR through a public records request, the education department’s misconduct investigator, Richard Farrell, was asked to investigate after Edeblut surfaced concerns about the book. Farrell, in turn, asked the Dover school district about the book, which students could access it and how the district handles book complaints.

In response, Dover Assistant Superintendent Christine Boston explained their book reconsideration process and confirmed that the book was available in the Dover High School library.

In the meantime, Dover administrators also received a separate complaint about "Boy Toy." In response, the district went through a process of evaluating whether the book should stay on its library shelves, in line with its official review and reconsideration policy.

Previous story: 'Boy Toy' to stay in Dover High School library; author addresses resident's removal bid

As the district held meetings to decide the fate of the book this summer and fall, it continued to receive letters from Edelblut about how it selected books.

“It was clear that we were being asked to reconsider our thought process,” Boston, the assistant superintendent, told NHPR this week.

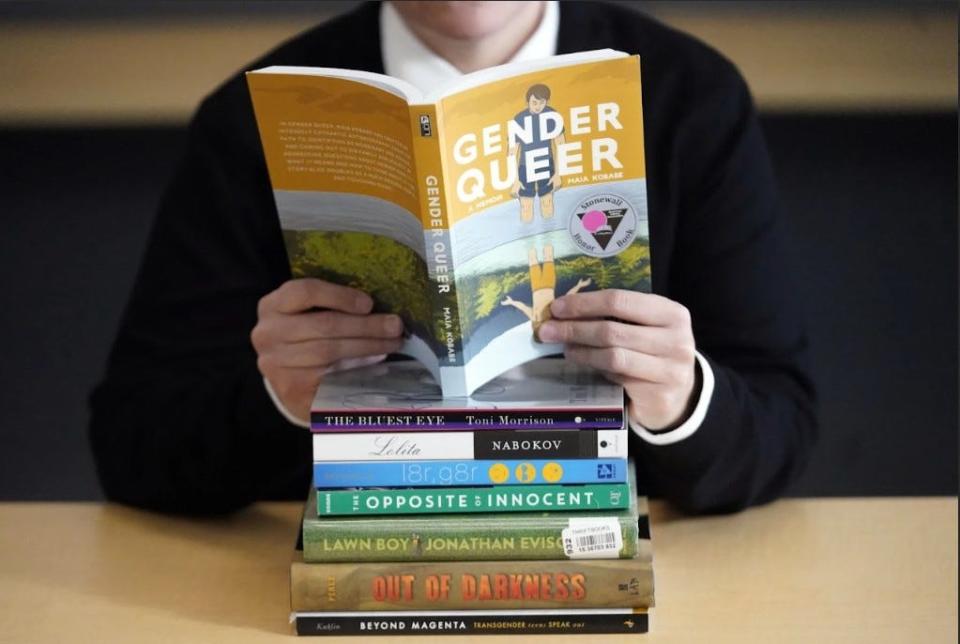

In July, Edelblut sent a letter to the Dover School District, asking for clarification on how it determines that it’s offering a “developmentally appropriate collection of instructional resources,” in line with state law. Edelblut specifically invoked the presence of sexually explicit material in "Boy Toy" and another book that’s been frequently targeted by bans across the U.S., "Gender Queer." He also raised concerns about students’ mental health.

The district responded with its own letter explaining that "Gender Queer." was not offered in its library, but it was in the midst of evaluating "Boy Toy," which it said was approved for those age 16 and older. Boston, the Dover assistant superintendent, said the commissioner’s letter appeared to suggest that these books could be harmful for students.

“I read it to mean if we kept books like this in the library, we were somehow jeopardizing students’ mental health,” she said.

In recent weeks, according to records obtained by NHPR, an education department investigator also contacted the district about a separate complaint that had reached the commissioner — this time about a poster on a classroom door.

“The poster says something about Reading Banned Books,” the investigator wrote.

Boston, the assistant superintendent, told the investigator they hadn’t received a complaint. The investigator replied: “I have to brief the Boss at some point. Please follow up??”

That same day, Boston responded the poster simply stated “Read Banned Books” and did not, in their view, warrant further action.

Defining ‘developmentally appropriate’

As Edelblut sent additional inquiries to the Dover School District this fall and summer, school administrators did not reply.

“We decided not to respond because we felt we'd already given a very clear response,” Harbron, Dover’s superintendent, told NHPR. “This was not his purview — that he could tell us what to do and not to do with books.”

But last month, the district pushed back with a more forceful response. In a letter dated Nov. 15, Harbon suggested that the commissioner’s goal “is or may be to try and override the elected School Board in Dover.” Harbron outlined librarians’ process for selecting books and why the district, after thorough review, deemed the book "Boy Toy" developmentally appropriate. He also requested two years’ worth of records reflecting the commissioner’s investigations, research, and communication about library and instructional material.

Edelblut, in a letter sent Tuesday, said his agency wasn’t trying to make decisions on behalf of local school districts but was instead trying to understand the criteria Dover uses to evaluate what is considered developmentally appropriate.

Specifically, Edelblut noted sections of an educational statute, ED 306.08, which require school boards to provide a “developmentally appropriate collection” of instructional materials and have a criteria for selection and replacement of instructional materials.

Several school officials and attorneys interviewed by NHPR said they were not aware of the Department of Education putting this much scrutiny on other districts’ decisions about books. But in an email to NHPR, a spokesperson for the Department of Education said it has had similar correspondence with other districts facing book complaints, with “the goal of perhaps finding some common themes that will be useful in these matters across the state.”

“That does not imply an objective of superimposing a singular standard across different communities so much as gaining an understanding so that we can all communicate effectively with our families and students,” they said.

Civil rights advocates step in

Local civil liberties and LGBTQ advocacy groups have also raised alarms about the education department’s inquiries in Dover.

In a series of letters released this week, lawyers from the ACLU of New Hampshire and GLAD rebuked the education department for what it called “alarming and extraordinary communications” with the Dover School District. Though Edelblut did not tell the district to remove books, the attorneys warned that his communications are “insinuating” that Dover should consider whether to remove texts from the library. Doing so could be a violation of free speech and anti-discrimination protections, they said.

Gilles Bissonette, legal director for the ACLU of New Hampshire, said that when it comes to debates about school materials, “developmentally appropriate” is subjective and sometimes leveraged to target books with LGBTQ themes and characters.

“Is this really about developmental appropriateness when you're dealing with a book that is so clearly appropriate and vital,” he said, “or is this really about viewpoint, because of what this book is about at its core?”

Bissonnette said his organization isn’t planning imminent legal action against the education department but “everything is on the table.” (The ACLU of New Hampshire and GLAD are among the groups currently suing the state over a law that limits how teachers can discuss race, gender and oppression in the classroom.)

The ACLU of New Hampshire and GLAD also noted their concern about a technical advisory issued by the Department of Education in September that, they say, significantly expands the definition of school materials that cover “human sexuality” and require parental notification.

The advisory says any curriculum in English and Social Studies classes that includes information about “human sexuality” could count as “objectionable,” and teachers should alert parents two weeks in advance of any such material in case they don’t want their kids to be exposed to it. According to the ACLU and GLAD, that interpretation is far broader than the law’s original intent, and could now include long-used material like Shakespeare’s, Romeo and Juliet, in addition to books with LGBTQ relationships.

The education department did not respond to questions from NHPR about the technical advisory or the concerns raised by the advocacy groups.

Across NH, a patchwork of policies on book complaints

Some of the conflict over books comes down to confusion over who’s responsible when someone objects to a book in a school library.

Lawyers with the ACLU and GLAD — and many public school officials — say the law is clear: Authority over school materials rests with school librarians, teachers, and school boards.

But Edelblut and others at the education department regularly field concerns from parents and residents who either disagree with their local district’s decisions, or do not think the process is sufficiently transparent. And the commissioner, who has aligned himself with parental rights efforts in the past, often follows up on these inquiries.

School boards are not required by state law to develop a complaints and review process for library books. However, a number of school districts have one.

Mark Giuliucci, a school librarian in Exeter who has worked with other librarians on intellectual freedom issues, said his district’s book reconsideration policy requires the complainant to fill out a questionnaire that, among other things, asks if they have read the entire book in question. The reconsideration committee is supposed to include a community member and student, and is advised not to take passages out of context but to form an opinion on “the material as a whole.”

While the education commissioner has emphasized “developmental appropriateness” as a metric in his inquiries about books, it’s not clear that schools use the same framework when evaluating challenged material.

When considering books to purchase, Giuliucci said many books are not marked for a specific age range, but librarians keep in mind that readers exist at different developmental levels across age groups.

“It's not necessarily fair to say a book is for 13-year-olds when a 14-year-old or a 10-year-old could get some meaning out of it,” he said.

Giuliucci said librarians often look for “mirror and window books” — books that reflect students back to themselves and give them insight into worlds different than their own.

Boston, Dover’s assistant superintendent, said her district takes book challenges seriously — though they can be time consuming. The review process for "Boy Toy," for instance, required about 100 hours of staff time and assistance from volunteer community members. She said the time, strife and media attention took its toll.

“This has been incredibly public. Educators are aware of this. Students are aware of this, and it definitely weighs heavily on the mind of educators,” she said. “I can't imagine how it feels to be an English teacher or a librarian thinking about, you know, every book in the library is under scrutiny or potentially something that can be weaponized against my profession.”

2022 story: NH education chief Frank Edelblut assailed for 'bigotry.' He sees family 'value system.'

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

This article originally appeared on Fosters Daily Democrat: Dept. of Education pressure on Dover schools on books raises alarm