NH Supreme Court closes door on partisan gerrymandering cases, taking lead from SCOTUS

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a landmark ruling: Federal courts cannot intervene in alleged cases of political gerrymandering, the court held.

Last week, New Hampshire’s Supreme Court followed suit. In a 3-2 decision, the court found that the state’s courts also do not have the authority to overturn legislative maps accused of partisan gerrymandering.

Now, legal experts say, any effort to stop future legislatures from passing political maps that favor one party over another will need to come from lawmakers themselves.

“The courthouse doors are shut,” said John Greabe, law professor and director of the Warren B. Rudman Center for Justice, Leadership, and Public Service at the UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law. “Both the federal courthouse doors and the state courthouse doors now.”

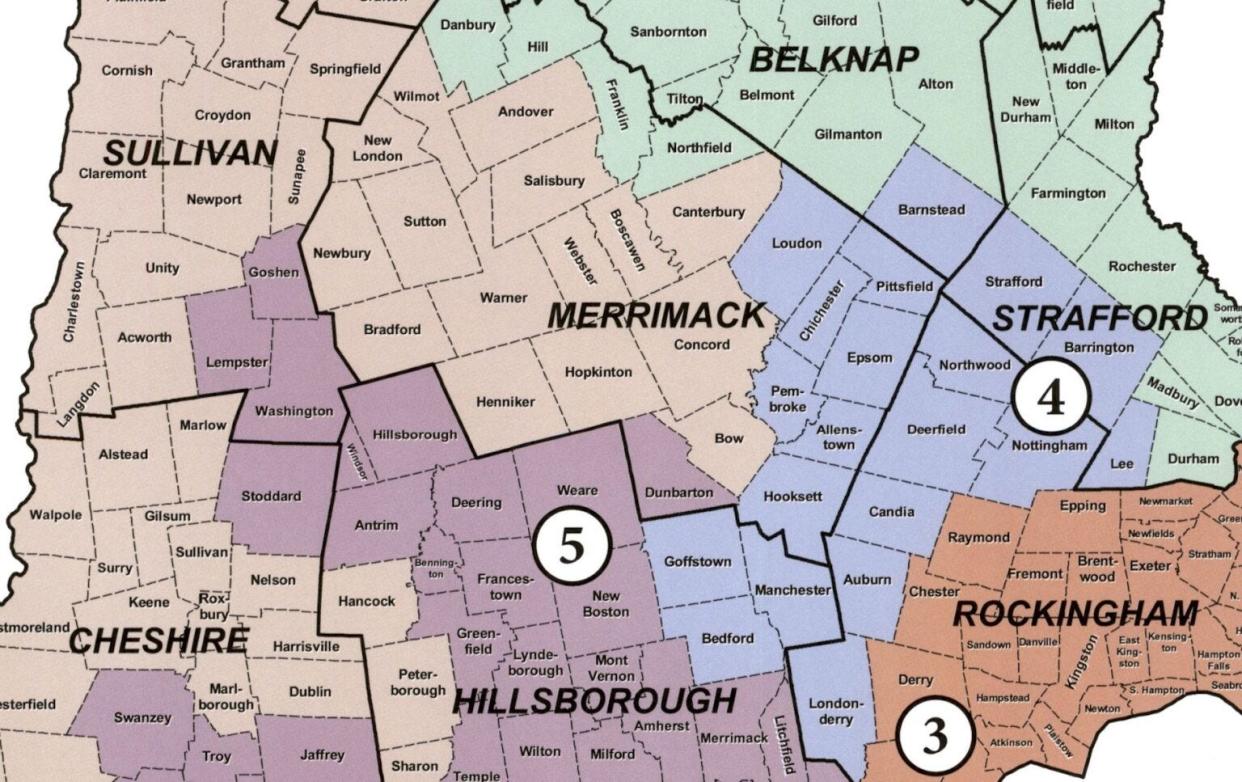

In the New Hampshire lawsuit, Miles Brown v. Secretary of State, the plaintiffs – a group of Democratic voters – argued that the drawing of the state Senate and Executive Council districts in 2021 tilted the map unfairly to Republicans by apportioning Democratic-leaning towns into specific districts to dilute their voting power.

But the court found that whether a map has been drawn to favor one party or another is a “non-justiciable political question” that would not be possible for the court to rule on.

“I’m not greatly surprised by this,” said Lawrence Friedman, law professor at the New England School of Law. While federal courts have inserted themselves into questions of racial gerrymandering – especially following the Civil Rights Act – political gerrymandering is different, Friedman noted.

Courts feel more comfortable making findings that certain state residents have been unfairly lumped into districts because of their race than because of their party affiliation, Friedman said.

“Unlike race, partisanship is not an inherent human characteristic, even in our hyper-partisan times,” Friedman said. “And I think a lot of courts are naturally reluctant to say how much is too much given that it’s kind of baked into the system: The party that wins the most votes gets to make the maps.”

“I think this decision is consistent with a court that always wants to move very carefully, even where the state constitution is concerned,” Friedman said.

Still, Greabe says the decision is a “big” one for New Hampshire. “It basically means that the judiciary is not going to force a reform in this area or place outer limits on what the Legislature can do.”

In the 2019 case, Rucho v. Common Cause, the U.S. Supreme Court held that partisan gerrymandering accusations could not be addressed by federal courts because they are political issues that should be resolved by voters and lawmakers. The court made it clear that its decision did not stop state courts from interpreting their own constitutions to adjudicate political gerrymandering claims.

But in the decision released last week, the state Supreme Court found that New Hampshire’s constitution does not give it a foundation to do so.

“Here, the plaintiffs have failed to identify any express mandatory constitutional provision or state statute addressing partisan gerrymandering in New Hampshire,” Associate Justice Patrick E. Donovan wrote in the majority opinion. “Further, we are not persuaded that a discernible standard for adjudicating partisan-gerrymandering claims exists.”

The decision gives New Hampshire lawmakers two options, Greabe noted: continue drawing the legislative districts themselves, or pass a law or constitutional amendment that explicitly allows the state courts to intervene or delegates the authority elsewhere.

The debate over a clear test

The journey to each court decision has been convoluted.

Both the federal and state rulings grappled with a longstanding legal quandary: “the political question.” That theory, solidified in the 1962 Supreme Court decision in Baker v. Carr, holds that there are certain times when federal courts should not exercise judicial review over the actions of legislatures because doing so would be inserting the courts too far into political matters.

Baker v. Carr did not stop federal courts from intervening on alleged gerrymandered maps. But it did lay out a six-part test for when a court is improperly inserting itself into the political question.

Two parts of that test are relevant to these recent decisions, Greabe said. First, a court can intervene if there is a textually demonstrable delegation of authority to that court in statute; in other words, if state or federal law explicitly says they can. Second, a court can get involved only if there is a judicially manageable standard the court can apply in order to determine if something is legal or not legal. The court needs a clear test.

In New Hampshire’s gerrymandering case, the Supreme Court held that neither of those conditions are met.

Neither the state constitution nor state statute lays out a clear direction that courts may throw out maps that have been politically gerrymandered, the majority held. To the contrary, the state constitution explicitly puts the districting power in the Legislature’s hands.

And even if the courts wanted to review gerrymandering allegations, there is no clear test to do so, the state Supreme Court ruled.

The plaintiffs had proposed using an efficiency gap analysis, in which the court compares the overall number of votes each party earned across the state with the percentage control that party received in each legislative chamber. In 2020, for instance, about 50 percent of the votes for state Senate went to Democrats – statewide – but Republicans controlled the chamber 14-10, according to an analysis by New Hampshire Public Radio. The efficiency gap analysis helps measure whether the way a map is drawn is producing “wasted votes” for one party.

But the court majority countered that other courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, had attempted to use those kinds of analyses and had not been able to determine a clear line beyond which a map would be unconstitutionally skewed.

In the end, if lawmakers want a test to be used, they will need to pass it into law, the court held.

The minority on the court disagreed. In his dissent, Associate Justices Gary Hicks, who retired last week after turning 70, and Senior Associate Justice James P. Bassett argued that the court should allow the case to proceed and to try to come up with a justiciable test.

“This case is about whether the plaintiffs can have their day in court,” Hicks and Bassett wrote. “Our colleagues have ruled that they cannot. For the first time, this court has declined to exercise jurisdiction over alleged constitutional violations on the ground that it cannot discern manageable standards for resolving them in the text of the constitution, or, in Justice [Elena] Kagan’s words, ‘because it thinks the task beyond judicial capabilities.’”

Up to the Legislature

In wrestling over what is an appropriate test for gerrymandering, the state court followed a similar anguished path as the U.S. Supreme Court. Initially, the federal court held that claims of political gerrymandering are justiciable, in the 1986 case of Davis v. Bandemer. But the majority in that decision could not articulate a clear test.

By the time the court took up the issue in Rucho, the majority had concluded that no test could sufficiently measure the level at which gerrymandering becomes unconstitutional, and thus the question could not be answered by federal courts. Throughout its decision, the New Hampshire court found the same, quoting from the Rucho decision extensively.

That outlook is not universal. Justice Elena Kagan wrote a dissent to Rucho that outlined what she argued was a workable test courts could use to determine unlawful gerrymandering. Kagan’s test has been influential in some states that have pursued measures to combat gerrymandering, Greabe said. Yet without the New Hampshire Legislature acting, the test will not be enacted in the Granite State.

“… Unlike other states that have codified limits on partisan gerrymandering or amended their state constitutions to limit or prohibit partisan favoritism in redistricting, New Hampshire has not done so,” Donovan wrote in the decision.

Greabe and Friedman pointed to one measure lawmakers could try: an independent redistricting commission that could help design maps with the objective of fairness.

Seven states used such commissions during the latest redistricting effort following the 2020 Census: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, and Washington, according to a database maintained by Justin Levitt of the Loyola Law School.

New Hampshire Democrats have tried several times to pass a measure. In 2020, Gov. Chris Sununu vetoed a bill to do so, and the Democratic-led Legislature did not have the votes to override it. Sununu argued that creating a commission would only push the redistricting decisions over to unelected representatives of party bosses. The task should be carried out by lawmakers, he wrote in his veto message.

“The New Hampshire constitution directs the Legislature – the most representative body in the country – to determine Congressional, legislative and executive council districts,” Sununu wrote. “We know our local representatives and senators personally, and we can hold them accountable for their decisions.”

Barring any political shifts, it will be up to lawmakers to determine how fair the process will be, Greabe noted.

“It’s going to require the Legislature to discipline itself,” he said. “And do legislatures do that? Do legislatures act in altruistic ways? We’re not seeing a lot of signs of that.”

This story was originally published by the New Hampshire Bulletin

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: NH Supreme Court closes door on partisan gerrymandering cases, taking lead from SCOTUS