NH voters head to polls in primary amid legal battles over new legislative districts

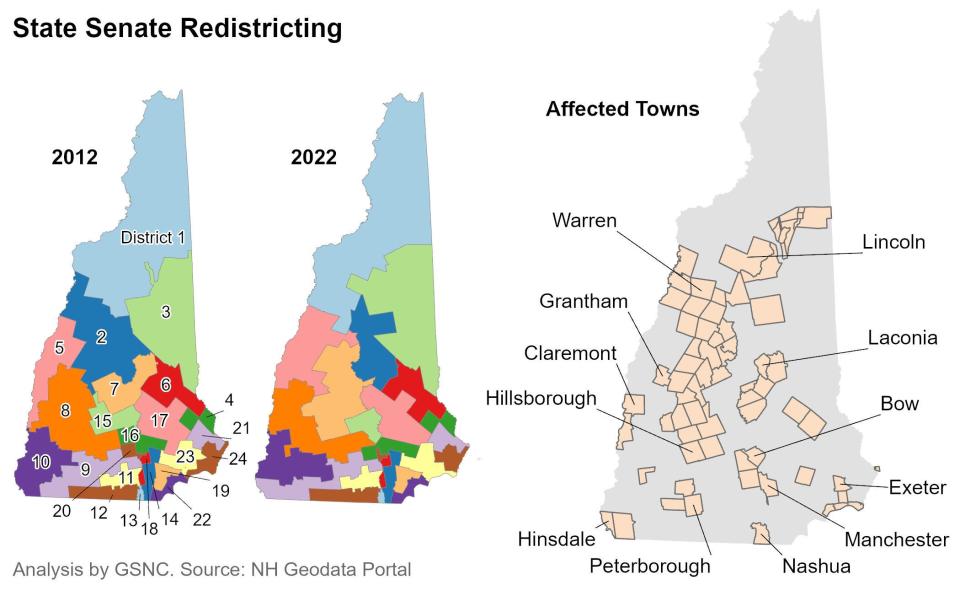

As voters prepare to vote in the New Hampshire primary election on Sept. 13, they’re hearing a lot about redistricting. New district maps for electoral office drawn by the Republican-dominated legislature face court challenges and in one case a gubernatorial veto, leaving voters to wonder if their experience at the polls will change from previous years.

The way districts are drawn can affect the outcome of an election, through what is known as gerrymandering, but the process does not change how or where people vote. Municipalities may decide to move polling stations, close polling stations or add new ones, but that has nothing to do with redistricting.

Lawmakers are required by the state and federal constitutions to redraw district lines to adjust for changes in population based on the U.S. census conducted every 10 years. Statewide elections for president, governor and U.S. Senate aren’t affected because the “district” is the entire state.

More: Sununu faces 5 GOP challengers from right in primary, but none with Trump endorsement

But when it comes to U.S. Congress, state Senate and House, and the Executive Council, every 10 years brings a new map drawn by the party in power, or an independent commission if the state Legislature has voted to approve one, which New Hampshire has not (although Democrats have repeatedly tried).

The Granite State, according to the federal constitution, has enough population to justify two representatives in Congress, which most voters in the state understand to mean we have two congressional districts.

Republicans in the state Legislature attempted to redraw the map to virtually guarantee a Republican in New Hampshire’s First Congressional District and a Democrat in the Second, but the result created such twisted district lines and moved so many communities from one district to the other that Republican Gov. Chris Sununu successfully vetoed the bill.

Ultimately the state Supreme Court hired a special master to redraw the congressional district lines. He moved five small towns eastward from CD1 to CD2 to restore the balance of population on each side, assuring that each district contains about half the state’s population.

More: How to prepare now to vote in 2022 New Hampshire primary on Sept. 13

Maps get complicated

That’s what non-partisan redistricting looks like. Gerrymandering looks like the plan developed by Republican legislators and vetoed by Sununu that moved 35 to 40 percent of voters from one district to the other. That has nothing to do with equalizing population and everything to do with obtaining political advantage.

The math gets more complicated as the number of districts increases. In the Executive Council, with only five members, each district has to accommodate one-fifth of the population.

Each of 24 state senators is supposed to represent 1/24th of the population, while each state representative is accountable to roughly 3,444 residents. (400 state reps multiplied by 3,444 gets you to New Hampshire’s population of roughly 1.3 million.)

“When you apply (those ratios) to various districts, the amount you are away from that ideal number, gives you a plus or minus percentage,” explains Republican State Sen. Jim Gray of Rochester, who led the redistricting effort in the past session. “A state legislative district, according to court decisions, has to be within 10 percent plus or minus of that ideal number.”

Congressional Districts have to be as equal as possible, but state legislative districts are allowed up to a 10-percentage point deviation.

Facing legal challenges

While the map for U.S. House has been settled, at least for now, the maps for Executive Council, state Senate and state House are facing legal challenges by Democrats and their supporters, or by municipal officials, not because they have failed to meet the required population distribution, but because they create an extreme partisan advantage, according to the lawsuits.

A guide to voter rights in New Hampshire: What you need to know before you cast a ballot

It’s unlikely that any of the legal challenges will result in changes to the new district lines before the upcoming election. Judges at the Superior Court and State Supreme Court appear unwilling to wade into the political waters of a redistricting case, particularly in the weeks before voting gets underway.

The cities of Dover and Rochester and various individual voters filed a complaint in Superior Court on July 26 against the Secretary of State and the State of New Hampshire, arguing that in several cases the House redistricting fails to meet a requirement in the state constitution that political wards or towns with sufficient population should have a dedicated state rep.

More: Dover, Rochester file complaint, pushing back against NH House redistricting

The municipalities or wards “unconstitutionally deprived” of a guaranteed state rep because they’ve been linked to nearby communities, according to the lawsuit, are Dover Ward 4, Rochester Ward 5, Lee, Barrington, New Ipswich, Wilton, Hooksett, Chesterfield, Hinsdale, Canaan, Hanover, Bow, Plaistow and Milton.

The lawsuit admits that larger towns or wards have to be linked to smaller nearby communities in some cases to maintain the right population per district but goes on to say that “the legislature should minimize violations of the State Constitution and enact only those violations necessary.”

Two towns together again

Not all large communities who lose their standalone status are troubled by the development. The town of Peterborough has stood alone as a voting district for state representative since the 2012 redistricting. In the past legislative session, the town was represented by Peterborough residents Peter R. Leishman and Ivy C. Vann.

“With this latest House redistricting, Peterborough is now with Sharon, which isn’t a bad fit, because it’s sort of a rural suburb of Peterborough,” said Leishman, who has represented the Peterborough area district for 12 terms. “Now three people will be running for two seats in the newly configured Peterborough/Sharon district.”

While the redistricting was well-received in Peterborough on the representative front, the situation is different when it comes to state Senate. In the new Senate district, Peterborough is looped in with Keene, which because of its size is likely to dominate district-wide voting.

“Whether Peterborough will have any chances of getting a senator in the future is slim to unlikely when you have Keene as the big giant in the district,” says Leishman. Peterborough resident Jeanne Dietsch represented Peterborough and nearby communities in the state Senate from 2018 to 2020.

Peterborough is now in the newly drawn Executive Council District 2, which runs up the west side of the state, from the Massachusetts border to Littleton, grabbing Democratic strongholds like Keene, Lebanon and Hanover along the way, while stretching east to grab Peterborough and Bow.

Peterborough is an example of a town that’s seen the shape of its districts for House, Senate, and Executive Council all change, and many others are in the same boat.

Too much movement?

According to the lawsuit filed by former Democratic NH House Speaker Terie Norelli and 10 other plaintiffs in May, such drastic movement of towns into new voting districts wasn’t necessary to adjust for population changes, when moving a few towns one way or the other in most cases (much like the U.S. Congress districts) would have sufficed.

Instead, the suit claims, “(The maps) were enacted to entrench Republican Party control over New Hampshire’s Senate and Executive Council regardless of the wishes of the electorate and will have that intended effect.”

“Under both plans, Republicans can attain overwhelming control of the Senate and Executive Council even if they amass less than half of the statewide vote. Meanwhile, just to win a bare majority of districts under either plan, Democrats must amass well more than half of the statewide vote.”

In their response to the lawsuit, which names Secretary of State David Scanlan as defendant, attorneys for the state do not deny that political considerations went into the redistricting plan.

“If New Hampshire wants to prohibit, limit or regulate partisan gerrymandering, the proper way to do that is through legislative action or a constitutional amendment,” according to Attorney General John Formella. “The New Hampshire Supreme Court has expressly precluded courts from considering political data or partisan factors in redistricting cases.”

A questionable case

As long as the population distribution meets the legal standards, the bizarre shape of a district or its obvious political configuration are “nonjusticiable” in the words of attorneys, unless the state decides to make it so through legislation or constitutional amendment.

The judge in the case is not likely to hear arguments until after the election, and she doesn’t sound predisposed to order new district lines.

“The Court questions whether the plaintiffs have stated a claim for which relief may be granted,” wrote Superior Court Judge Jacalyn Colburn in a June 21 order. “The New Hampshire Supreme Court has held that political considerations are tolerated in legislatively-implemented redistricting plans.”

Editor’s Note: Sample ballots for the Sept. 13 primary election are available at sos.nh.gov/elections.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: NH voters head to polls as legal battle over redistricting proceeds