How NH's mental health care system closed gaps but why a 'tremendous amount' remain

Ebony Martin worked in warehouses, parking garages, fast food restaurants and a sober house before she found her life’s calling as a peer-support specialist — a critical and expanding role in New Hampshire’s mental health system.

"I’m busy spreading compassion and joy." That message on a co-worker’s coffee mug speaks to Martin’s role helping clients lead fulfilling lives, despite challenges that include substance misuse, anxiety, depression, borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia, among other mental illnesses.

Martin and her clients at Greater Manchester Mental Health Center — typically 10 to 15 a week — go for drives, share coffee or meet wherever they’re comfortable. Martin shares her personal story.

This is the eleventh story in a year-long collaboration on mental health between Seacoast Media Group, New Hampshire Union Leader and Dartmouth Health. https://www.seacoastonline.com/in-depth/news/2022/05/20/mental-health-new-hampshire-series-seacoastonline-union-leader/9821991002/

“When you hear someone who’s been through what you’re going through, it’s a different outreach. You see the light go on in their eyes. They think, ‘Oh my goodness, someone gets it.’ When someone has walked that path and gotten to the other side, they call it peer magic," she said.

Martin serves as a coach and role model, pivotal functions in a tentacled network where demand is quickly outpacing supply. As the state and nation grapple with a mental health crisis across all demographics and age groups, peer support specialists are indispensable links in a network seeking new ways to provide meaningful, lasting treatment.

They are part of a mental health team approach that includes doctors, nurses and social workers − and the state could use more of them.

"Their expertise is lived perspective," said Cynthia Whitaker, executive director of Greater Nashua Mental Health, which has 13 peer support specialists on staff. "People should have the opportunity to try peer support just as they would any other option for mental health."

As policymakers, mental health advocates and patients question whether New Hampshire’s mental health system is nimble, proactive and extensive enough to meet current and future demand, peer-to-peer support increasingly is part of the answer.

“I’ve been told I help them feel normal, even though I don’t think there is such a thing,” said Martin, whose clients include people who battle mental illness and substance misuse disorders. “If people knew they could share their experience and help someone, then more people would want to do this.”

Persistent challenges

New Hampshire’s mental health system is a work in progress, with troughs, bumps and peaks, many encountered in the past three years.

“We are very proud of how far our system has come, and there’s a tremendous amount to do. This is an all-hands-on-deck problem,” said Morissa Henn, associate commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

Peer-to-peer support, often used in addiction recovery, now is used to treat a range of mental illnesses, common and complex. NH Rapid Response, a statewide initiative begun in January 2022, dispatched 7,084 mobile crisis teams in its first year. Mental health care via telehealth, sparked by pandemic safety precautions, endures for clients and practitioners who prefer it. Hampstead Hospital, purchased by the state last year, reopened as a psychiatric hospital for children.

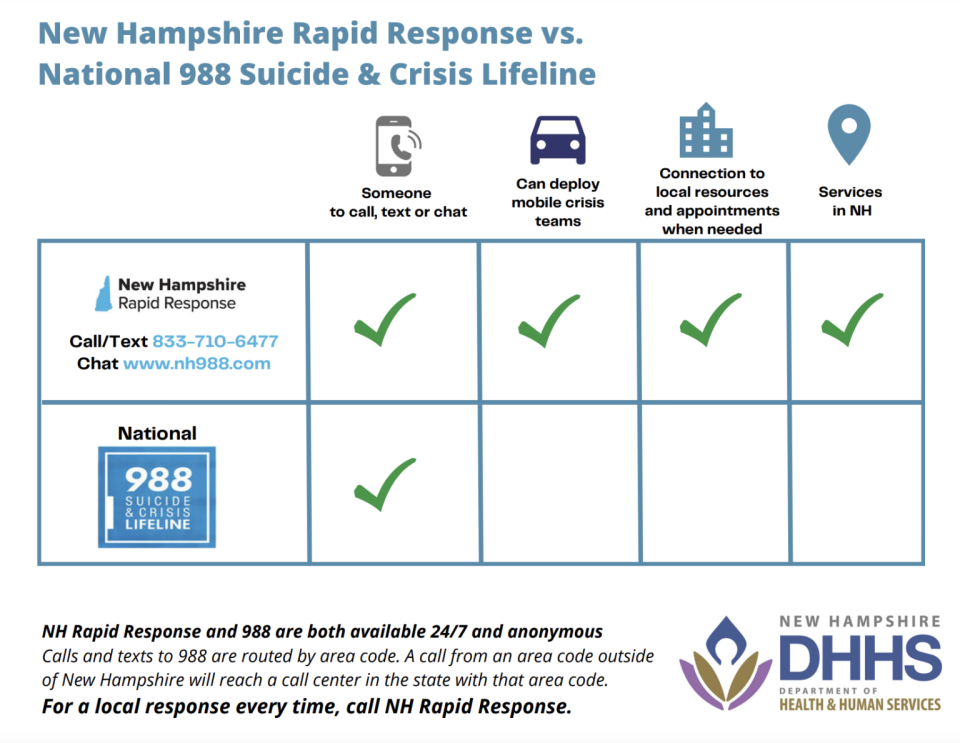

Today, critical time intervention helps involuntary mental health patients conquer daily hurdles for nine months after they're discharged from hospitals. NH 988, a statewide suicide prevention and crisis hotline, went live in July. Sixty transitional housing beds are planned across the community mental health centers.

The state's first psychiatric residential treatment center is in progress. And the state and SolutionHealth, owners of Elliot Hospital, have agreed to build a 120-bed psychiatric hospital in southern New Hampshire.

But pieces are still missing. Issues that linger include capacity, workforce challenges and funding.

“There’s no silver bullet,” said Roland Lamy, executive director of the New Hampshire Community Behavioral Health Association, which represents the state’s 10 community mental health centers, with locations from Colebrook to Keene. “We got here because demand grew at a rate faster than we could adjust.”

Funding for community mental health centers fluctuates year to year depending on Medicaid reimbursements, which account for as much as 80% to 90% of their annual revenue. That makes it difficult for them to expand.

“We have wonderful people who are really dedicated. We shouldn’t have to worry about where the next buck is coming from,” said Rik Cornell, a social worker and vice president of community relations at the Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester. The state’s largest community mental health center serves roughly 11,000 people each year, almost half of whom suffer from severe and persistent mental illness, he said.

“New Hampshire needs an adequately funded mental health system, not a poorly resourced one,” said Patricia Carty, executive director of the Manchester center. “That will raise the bar on community wellness, even when we’re having workforce shortages.”

High demand, low capacity

One in five adults and one in six children are affected by mental illness, according to 2022 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Kaiser Family Foundation/CNN Mental Health in America Survey. More than half the families in the Kaiser/CNN survey said they or a loved one had experienced a mental health crisis in the past year.

Young adults ages 18 to 29 reported the most mental health concerns, with many saying they were unable to get treatment.

According to the state Department of Health and Human Services, one in four New Hampshire residents is experiencing some form of mental health distress.

“This is a regional and national crisis for all children and adults,” said Dr. William Torrey, chief of psychiatry at Dartmouth Health, who has spent 38 years in the field.

Demand for inpatient and outpatient care currently “exceeds our capacity at all levels,” Torrey said. More people are seeking care, more are acknowledging mental illness and addiction struggles in themselves and loved ones, and more are advocating for mental health care — which is good. “They see the extreme need for services.”

Mental health systems are created by the states, not the federal government, and are tasked with adapting to changing needs. A number of federal agencies and nonprofits, including the National Council for Behavioral Health, Zero Suicide and SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, furnish research and guidance.

When it comes to forging a lasting, successful mental health system, “We have some components, but we need a strategic plan of what to accomplish incrementally” in one to two years, two to five years, and five-plus years, said Lamy at the Community Behavioral Health Association.

The need for prevention

Providing mental health treatment regardless of income with ample inpatient and outpatient services, especially in the face of workforce shortages that deepened during COVID, remains a challenge nationwide — and a multimillion-dollar puzzle for states like New Hampshire.

To improve the state’s mental health network, more "step-up and step-down" services are needed, including intensive outpatient programs that offer counseling and skill-building several times a week, and partial hospital programs that provide half- or full-day sessions to patients discharged from hospitals and residential care, according to mental health experts.

Help support quality local journalism like this. Subscribe today.https://subscribe.seacoastonline.com/offers

Investing in the community mental health system — which furnishes individually tailored, team-based care — “is probably the most important investment the state can make,” said Torrey at Dartmouth Health.

Katja Fox, director of the behavioral health division at the Department of Health and Human Services, calls the community mental health centers “a bedrock from which to build.”

Community mental health centers, with more than 40 primary and satellite locations around the state, provide individual and group counseling, emergency response, medication management and peer-to-peer support for more than 60,000 New Hampshire residents annually, according to the behavioral health association.

Three mental health centers in Nashua, Manchester and Dover have primary care providers on site.

Telehealth was a boon to coverage. “We’re providing more outpatient services with less workforce than ever before,” Lamy said. “But I worry about burnout. We are definitely doing more with less."

About 250 positions at community mental health centers across the state are unfilled. That ripples to longer waits for first-time appointments.

“The people who get delayed? There’s a really good chance they’ll be worse off than if they got services now,” said Lynn Stanley, director of the New Hampshire chapter of the National Association of Social Workers. It becomes harder to catch early-stage struggles.

“I don’t think we’re doing a very good job with prevention," she said. "Prevention costs less than a crisis.”

New Hampshire's North Country struggles

In her 28 years at the community mental center serving Carroll, upper Grafton and Coos counties, Suzanne Gaetjens-Oleson has never witnessed this level of staffing crisis.

Northern Human Services has 16 satellite offices, from Wolfeboro to Colebrook, in a region that covers more than 40% of the state and stretches to the Canadian border.

To Gaetjens-Oleson, a licensed mental health counselor and the agency's chief executive officer, the issue for New Hampshire policymakers is not so much a matter of improving a system as it is addressing underlying social and economic factors.

It’s a question of how to create more trained people to hire — and have a sufficient supply of affordable, local places for them to live.

To serve patient demand in the state’s northern half, NHS staff shift locations or work remotely, scrambling to fill rotating gaps.

Its locations in Wolfeboro and Conway — two mental health clinics and a group home for people with disabilities — are down eight or nine clinicians, which makes a big dent in service.

It’s tough to find replacements, given the dearth of affordable housing and the high costs of renting and owning in the two resort areas, where prices rose even further during the pandemic, Gaetjens-Oleson said. Mental health clinicians travel from Berlin or Maine because they can’t afford to live locally.

“We’ve never gone without qualified people trained to do this work. The pipeline has dried up," she said.

“We need to be funding people to go to school who work in our programs," she said. "We’re a system dependent on Medicaid” without regular increases that cover salaries and escalating care costs.

As in other rural regions, the North Country's challenges include a lack of transportation and higher rates of poverty.

“It’s not like a business where you can raise your prices when salaries go up," Gaetjens-Oleson said.

How a different education track could create a workforce pipeline

Creating a workforce pipeline that starts in high school and continues with financial support would make a difference, according to Lamy and others.

“We have jobs ready for them when they come out of school. We have kids with interest and an opportunity to turn them into future providers. But we don’t have the ‘interest pipeline’ in our education system,” said Lamy.

Wages for entry-level clinicians need to increase, especially since many are trying to live independently while repaying college loans. A master's degree in social work requires two years of on-the-job training with clinical supervision, in addition to coursework and credits. The internships are almost always unpaid.

“We have to utilize bachelors-level clinicians more” — including on crisis teams, said Susan Stearns, executive director of NAMI-NH, the state’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “We want people to come into the field and not feel financially crippled by good deeds.”

Roberta Baker can be reached at rbaker@unionleader.com.

Read more in the series: A Year-long Mental Health Awareness Journey

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: NH mental health services help more but workforce limits mean gaps