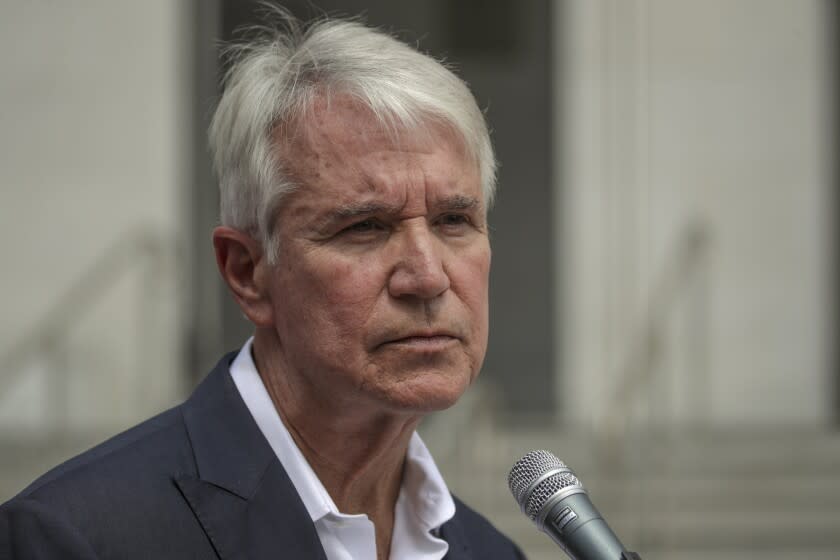

Nicholas Goldberg: L.A.'s district attorney explains the persistent racism in police culture

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

George Gascón, the district attorney of Los Angeles County, is appalled by the virulently racist text messages that went back and forth among more than a dozen Torrance police officers.

And who wouldn’t be? It’s sickening to read the texts. The references to apes, savages, nooses and the N-word, not to mention the cavalier discussion of racial violence — this is discourse of a sort rarely aired in public. It’s not veiled prejudice; it’s not “structural racism” or “implicit bias.” This is full-on hate speech by police officers against the citizens they’re supposed to be protecting.

“It was shocking to see it,” said Gascón, who has been involved in the investigation from the start. “Not only because it was so vile, but because there was so much, involving so many officers.”

As I talked to him more, though, it became clear that he’s shocked and, at the same time, not shocked, because, after four decades in law enforcement, Gascón is all too familiar with the culture of racism that has long been part of policing in America.

Few people can match his experience. He began as a uniformed cop in the Los Angeles Police Department in 1978. Eventually he became a sergeant, a lieutenant, a captain and an assistant police chief. He left L.A. to become a chief, first in Mesa, Ariz., and then in San Francisco. After 31 years in policing, he became district attorney in San Francisco, and in 2020 was elected D.A. in Los Angeles County.

So he’s seen a lot of bad stuff in his day.

I began by asking what he himself had come up against as he made his way from street cop to the top job. He noted that when he joined the LAPD, there was only one Black person in his class at the police academy, and two Latinos, including himself. No Asian Americans.

He remembers being told coldly by his fellow officers not to speak Spanish to people on the street because, you know, “this is America.” He says he saw how racial bias affected the way officers performed their jobs — and not just white officers, but Black and Latino officers as well.

Did he hear the N-word bandied about? Of course he did — and “unkind words” about Latinos as well.

“African American and Latino police officers of my generation developed a shield around themselves,” Gascón told me. “If you were to pick a fight every time, especially in the early days, my goodness, you’d be fighting every day.”

Over the years, Gascón has seen his share of race-related scandals, including one most recently in San Francisco also involving bigoted text messages among cops. That's why when he heard about the two officers in Torrance who in January 2020 allegedly spray-painted a swastika onto the back seat of a towed car, he immediately suggested that investigators look at texts the officers had sent.

So far, that has led to 15 Torrance cops being put on administrative leave.

The texts, which were revealed by The Times’ James Queally last week, put in jeopardy hundreds of criminal cases in which the officers had testified or made arrests. Gascón‘s office has already dismissed more than 35 cases as a result.

In their texts, the officers were vicious about “gassing” Jewish people, assaulting people in the LGBTQ community and using violence against suspects. But Black people were frequently the target.

“I wish I could say Torrance was unique, but it isn’t,” Gascón said.

He emphasizes that most law enforcement officials are not racist. Most are “working hard to do the right thing.” But a substantial minority, he says, harbor racist feelings — “and too often, there’s a high level of tolerance for it,” he adds.

And yes, he says, bigoted beliefs affect the way people do their jobs. How could they not?

There’s not much question — and these are my words, not Gascón‘s — that a substantial minority of police officers see themselves as the final line of defense in a chaotic and hostile world, where danger lurks around every quarter. When they spend disproportionate amounts of time policing Black and Latino neighborhoods, an “us-versus-them” mentality is all too often the result.

Gascón sees a cycle of “overpolicing” and “overcriminalizing” of poor people and people of color — a cycle that infects arrests, prosecutions, sentencing and prison life.

He remembers being in the Army during the Vietnam years and being trained to see the enemy as less moral, less right-thinking and, ultimately, less than fully human. It helps when you’re going into battle.

“Policing is no different,” he said. “You start building this belief that you have a higher moral ground than the people you’re arresting and you begin to accept the dehumanization of the people you’re policing. And who are they? African Americans and Latinos.”

Gascón says he has little patience for law enforcement leaders who “circle the wagons” when accusations of racism are made, hoping to protect their institutions. He noted that the chief in Torrance, Jeremiah Hart, has behaved courageously and aggressively with regard to the current investigation.

Gascón was elected D.A. in part because he argued that cops must be held accountable for their misconduct. His predecessor, Jackie Lacey, was harshly criticized for not prosecuting police officers who had killed unarmed suspects.

These days, Gascón is getting mixed reviews. Fear of crime is up (although the data on crime itself is complex and ambiguous) and tolerance for his criminal justice reform agenda may be waning. There’s plenty to debate about what the best methods are for protecting communities from crime.

But there’s nothing to debate about his assertion that law enforcement leaders must stand up to racism wherever it shows its face.

That kind of rot needs to be rejected unequivocally from the top.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.