Nicholas Goldberg: Trump's view — How can I make money off it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What’s the difference between songwriter-satirist Tom Lehrer and narcissist ex-President Donald Trump? That’s probably not a question you’ve ever thought to ask.

But two recent stories — both about intellectual property law — have helped answer that question nevertheless.

Let’s take them one at a time.

Many people today don’t remember Tom Lehrer. He wrote songs that took on social and political issues in the 1950s and 1960s; his sardonic, black-humor parodies made fun of nuclear war, the Boy Scouts, Catholicism, bigotry, air pollution, cannibalism, masochism and math, to name just a few of his subjects.

His songs have lyrics like “So long, Mom, I’m off to drop the bomb” and titles like “(I’m Spending) Hanukkah in Santa Monica.” The latter included the unforgettable line “I spent Shavuos in East St. Louis.”

He wrote an entire song based on the periodic table of elements, which includes this verse:

“There’s sulfur, californium and fermium, berkelium

And also mendelevium, einsteinium, nobelium

And argon, krypton, neon, radon, xenon, zinc and rhodium

And chlorine, carbon, cobalt, copper, tungsten, tin and sodium.”

I was always partial to “Vatican Rag,” which he said he wrote for the Roman Catholic Church to help it "sell the product." In it, he described going to confession, saying: “There the guy who’s got religion’ll tell you if your sin’s original.”

Lehrer released records, played the Cambridge coffee shop scene and San Francisco nightclubs and became world famous before mostly disappearing from public view and going back to being a math teacher, much of the time at UC Santa Cruz. About songwriting, he told the Washington Post: “My head just isn’t there anymore.”

But his songs remained popular and he presumably continued to make money from them.

Then, late in life, he decided he was done profiting from his work. A couple of years ago he announced that he intended to put all his music into the public domain. In late November, he posted another note on his website saying that “all copyrights to lyrics or music written or composed by me have been permanently and irrevocably relinquished.”

“In short,” he wrote, “I no longer retain any rights to any of my songs. So help yourselves and don’t send me any money.”

OK, I’ll admit I found this moving, an example of a well-known person putting the public good over the private good, at some financial cost to himself. It’s true that Lehrer is in his 90s and, as far as I can tell, has no children, although surely he’s got heirs of one sort or another. Admittedly, this is not as big a deal as if we heard that the songs of Bob Dylan or Paul McCartney were suddenly free for public use (which they aren't). But Lehrer’s gesture is generous and selfless nevertheless, because the public domain is, in the end, the public domain.

People who want to use or perform or record or rearrange or tinker with his songs may now do so "without payment or fear of legal action," Lehrer wrote.

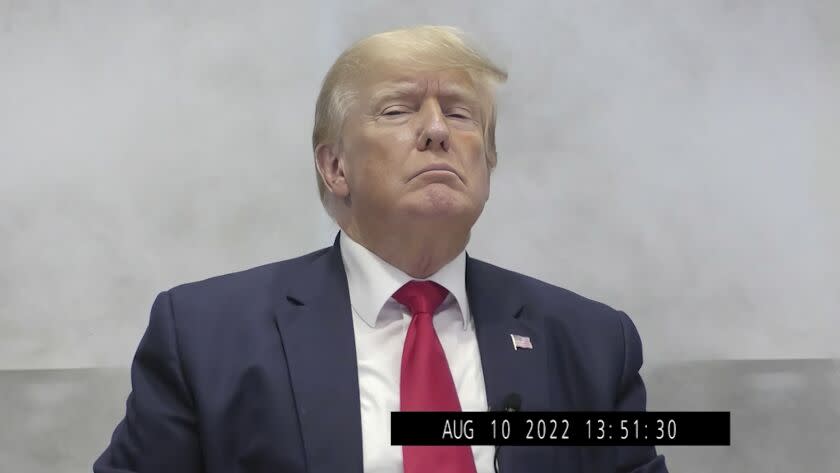

Which brings us to Trump, whose attitude toward everything — including the United States of America — is quite the opposite. His mantra is: How can I control it, how can I keep it for myself, how can I prevent others from profiting from it and how can I turn a buck off it?

That became clear yet again with the recent report of the House Jan. 6 committee, which unearthed an email from Trump-era White House Deputy Chief of Staff Dan Scavino showing that the then-president had sought to obtain a trademark for the phrase “rigged election.”

The email, written just days after the 2020 election and titled “POTUS requests,” was addressed to Trump son-in-law and advisor Jared Kushner. It said: “Hey Jared! POTUS wants to trademark/own rights to below, I don’t know who to see — or ask.”

Below, the phrase "Rigged Election!" is highlighted in the email. Kushner forwarded the request on to various aides, saying, "Guys — Can we do ASAP please?"

Had Trump been successful, the goal presumably would’ve been to sell merchandise using the phrase, raising money for himself or his campaign or his legal defense or whatever — and barring others from using the phrase for profit. "MAGA," step aside; here come the “Rigged Election” T-shirts, cups and baseball caps.

What's especially galling about it is that Trump would have been profiting off an utter lie, a cynical political manipulation that threatened to undermine American democracy: the pretense that the 2020 election had been stolen from him thanks to the manipulation of the electoral system by denizens of what he liked to call “the swamp.”

In the end, Trump did not successfully trademark the phrase, or perhaps was talked out of it by his lawyers. The rest of us can continue to sell “Rigged Election” caps if we choose to.

Lehrer, for his part, didn’t continue writing songs long enough to have had an opportunity to skewer Trump, which would have been delicious, I’m sure. Lehrer loved nothing more than ridiculing hypocrites.

Unfortunately, he got out of the satire business because it no longer seemed like an appropriate way to deal with the world. “Today, everything just makes me angry, it’s not funny anymore,” he said back in 2002. “Things I once thought were funny are scary now. I often feel like a resident of Pompeii who has been asked for some humorous comments on lava.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.