Nicotine sickness: the latest vaping scare

Sharon Levy, director of the adolescent substance use and addiction programme at the children’s hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, is quick to recall the first time a teenager with vaping-induced nicotine poisoning arrived at her clinic.

“This was about a year and a half ago,” she says. “I remember sitting, talking with him about his experiences using [the e-cigarette] Juul, and it became quite clear to me that the symptoms he had were basically nicotine toxicity. Nicotine is sometimes used as a pesticide in very high levels, and his symptoms were quite similar to people who had been exposed to it agriculturally. This suggested he was getting a far higher dose of nicotine through this device than you might expect.”

In what is becoming known as “nic-sick”, Levy has since seen the number of teenagers suffering from similar nicotine overdoses continue to rise. “Kids vomiting or experiencing headaches is common,” she says. “But it can get even more dramatic than that. I’ve had patients who get dizzy or lose their orientation. Sometimes I’ve even had kids tell me they’re disassociating while vaping, and they suddenly can’t remember where they are. Elsewhere, cases of seizures have even been reported. These are pretty novel symptoms among nicotine users – you don’t see this in cigarette smokers.”

In total, over the past year, Levy and her team have dealt with 181 cases of teenagers with what’s medically termed “nicotine use disorder”, although she makes it clear that almost all of them have resulted from vaping.

Many adolescents are already having respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough or shortness of breath

Sharon Levy

This is just a small snapshot of the current epidemic of vaping-related illnesses sweeping through the United States, all linked to the continuing surge in e-cigarette use. The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) recently released National Youth Tobacco Survey found that more than five million American teenagers have used e-cigarette products in the past month, with nearly a million using them daily, making vapes the biggest substance use ever in this age group.

The study went further to conclude that more than a third of high school students who use e-cigarettes are vaping at least 20 days per month, along with a fifth of middle school users, rates which scientists suggest indicate increasing dependence on the products.

“That’s a big escalation from a few years ago when it was mostly experimental use,” says Neal Benowitz, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco’s Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education.

But while the 2,290 incidences of vaping-related lung injury across the US, including 47 deaths, have captured the headlines over the past couple of months, Levy believes that these acute cases are merely the tip of the iceberg. Her research suggests that far more teenagers may have unknowingly already incurred the beginnings of lung illness through vaping.

“This summer we began screening adolescents for more modest signs of disease, and if you take a detailed pulmonary history, many of them are already having respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough or shortness of breath,” she says. “They’re not the severe problems which have caught our attention, but this is a spectrum. There’s a much more mild form of the disease, and presumably if you continue vaping over time, it will get worse.”

For addiction specialists, this is of particular concern because there are increasing suggestions, from current and ongoing scientific studies, that vaping has opened up a new frontier of nicotine addiction. With the potential to afflict an entirely new generation of individuals, it may have far-reaching consequences.

Palatable, potent vapes

Central to the vaping crisis is the rise of Juul, the American e-cigarette giant, who are widely credited with having transformed the market over the past four years with their innovative technologies, making vapes both more palatable and potent.

Back in 2015, the most popular e-cigarettes had nicotine concentrations ranging from 1% to 2.4%. Often clunky, battery-powered devices which converted cartridges of nicotine solution into a breathable mist, the caustic nature of the vapour imposed a limit in practice on how much inexperienced users would inhale. This all changed when Juul introduced their then groundbreaking pods of salted, flavoured nicotine, reducing the harshness of the vapour and making it possible to inhale far more, and for much longer. Most controversially, the company debuted pods with a nicotine concentration of 5%, arguing that with 480,000 Americans dying from smoking every year, the higher concentration was necessary to persuade chronic adult smokers to switch from cigarettes to vapes.

However the sleek products, thousands of flavours and powerful rushes also proved enormously popular with teenagers. By July 2019, Juul had claimed more than 73% of the total e-cigarette market, and a new study found that 60% of high school students who use e-cigarettes opt for a Juul product.

Scientists now agree that the greater levels of nicotine in the Juul products make them substantially more addictive, with some drawing parallels to the early years of the tobacco industry. “Early on the tobacco companies had to admit that they had adjusted nicotine levels in tobacco in order to get people addicted,” says Sally Huey, assistant professor at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies in Washington DC. “If you think about what’s happening with vaping, they’ve potentiated it by using these nicotine salts, so it gives a bigger rush.”

Related: Breaking up with my Juul: why quitting vaping is harder than quitting cigarettes

The potency of some vapes has raised the question among some researchers of whether vaping is more addictive than smoking cigarettes. While the data on that remains unclear, what we do know is that the patterns of use make it a very different type of addiction, with anecdotal reports of teenagers using vapes multiple times an hour, suggesting that it’s far harder to keep track of just how much you’re vaping.

“People have pointed out that when you finish a cigarette, that’s a sort of stop cycle,” says Levy. “But with a Juul you’d have to go through a whole pod, which is equivalent to a whole pack of cigarettes. So, the stop signal is much further away.”

Risks of long-term addiction

One of the reasons scientists are particularly concerned about the rampant levels of teenage vaping in the US is because studies have repeatedly shown that the earlier nicotine use begins, the greater the risk of nicotine dependence in later life. While e-cigarettes were initially marketed as a healthier alternative to smoking, the data shows that teenagers who become addicted to vaping are actually much more likely to progress to smoking cigarettes.

“As an example, there was an analysis published two years ago which found that kids who used e-cigarettes had about three to four times the likelihood of subsequently initiating combustible cigarettes compared to their peers,” says Jessica Barrington-Trimis, assistant professor at the University of Southern California Institute for Addiction Science. “This is because the earlier kids start using nicotine, the bigger the impact on the developing brain. The brain adapts to accommodate the nicotine, and the development of nicotine dependence is much more pronounced.”

Teenage exposure to high levels of nicotine may have long-lasting effects. Levy has already observed signs of what she describes as “complete behavioural dysregulation”, with hooked teens describing problems with attention, concentration – some even dropping out of school as a result.

“The areas of the brain involved in higher cognitive processes such as planning or impulse control take until the age of 20 or beyond to complete development, and exposure to nicotine will interfere with that,” says Huib Mansvelder, professor of neurophysiology at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. “In both lab animals and humans, studies have shown that early nicotine exposure can affect the ability to concentrate and focus for years or even decades after.”

In addition, while nicotine has long been considered one of the more benign components of cigarettes when it comes to their carcinogenicity, genetic data suggests that it may play a greater role in the development of cancers than previously thought. “From population genetics, we know that if you have certain genetic variants, exposure to nicotine seems to increase the likelihood that you will develop lung cancer,” says Mansvelder. “It’s still far too early to conclude that e-cigarettes definitely are carcinogenic, but from what we know, being exposed to nicotine vapours seems to be a bad idea, for adults as well as teenagers.”

Tackling the ‘perfect storm’

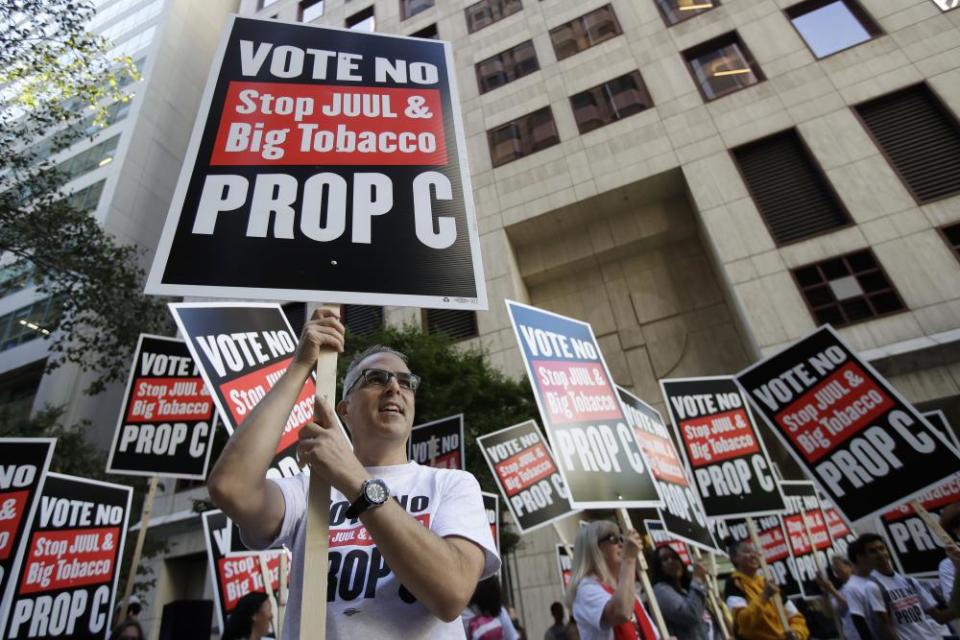

Scientists believe that the main reason that the teenage vaping crisis has been more prevalent in the US than in the UK or Europe is because of a lack of regulation around both the marketplace and advertising. So far, Juul have been able to sell their products without FDA approval regarding their safety, while e-cigarette manufacturers have been allowed to target younger age groups through social media platforms and YouTube, as well as conducting large-scale campaigns through TV, radio and billboards.

There are standardised procedures for helping people quit smoking – but no one knows if they’ll work for vaping

“What was unique about Juul was the social marketing campaign which was really attractive to kids, and the lack of regulatory oversight,” says Judith Prochaska, associate professor of medicine at the Prevention Research Center of Stanford University, California. “We haven’t had this kind of advertising for tobacco since the 1970s. The FDA has been very hands-off with the e-cigarette marketplace, and while retailers are not supposed to sell these products to kids under 18, there’s a lot of evidence to show that’s not upheld. It was the perfect storm.”

Over the past year, Juul has closed down its social media accounts and the FDA has now demanded it submit safety and efficacy data on vaping products by spring next year. However, new investigations have revealed that the company is lobbying for stronger and more addictive products to be sold in the UK – where, because of EU regulations, vapes currently cannot have a higher nicotine concentration than 2% – following Brexit, as well as a lift on advertising restrictions.

In the meantime, for the many teenagers addicted to vaping, the future is uncertain. For while there are standardised procedures for helping people quit smoking – ranging from nicotine replacement therapy to last-resort drugs such as bupropion or varenicline – no one knows whether the same methods will work for vaping addiction.

Levy suggests that for teens who have already begun to experience cognitive and behavioural dysfunction as a result of excessive vaping, longer-term ancillary support may be required to help them resume their education and deal with these problems. However in many states, few such programmes exist.

One major problem is trying to convince addicted teenagers to actually commit to quitting nicotine in the first place. But unless this happens, science suggests that many of these vapers will ultimately end up using both e-cigarettes and cigarettes, with potentially grave health consequences.

“I doubt that the future will just be a generation of people vaping,” says Prochaska. “There’s a study called Path which shows that adults and kids move between products. A lot of these vapers aren’t just going to stay with one type of tobacco product; they end up switching, and so you end up with a new generation of addicted smokers.”