The night KKK attacked Charlie’s Place, Myrtle Beach’s melting pot during segregation

Charlie’s Place pulsed with rhythm and blues, known then as “Black music,” spilling from the jukebox and throughout the streets of The Hill, Myrtle Beach’s black neighborhood.

Club-goers, Black and white, danced together, developing steps to what would later be known as the Shag, South Carolina’s state dance.

Myrtle Beach’s most prominent Black club was one of the few spots where both races could come to dance and hear the likes of Billie Holiday and Little Richard perform during the Jim Crow era with no trouble, until one summer night in 1950.

Black and white people dancing together was dangerous. The Horry County sheriff at the time had, on multiple occasions, warned against it. And on that night, the Ku Klux Klan aimed to put an end to it in Horry County.

The Sun News spoke with multiple people who lived through the KKK attack at Charlie’s Place and still live in the neighborhood. But the majority of those who remembered what happened the night of August 26, 1950, are deceased and the events of that day were under reported by local news outlets except for a handful of articles in The Sun News’ archives and an FBI investigation detailing the shooting.

Around midnight, a group of white-hooded men approached the club and opened fire on dozens of Black and white people who were dancing together. The robed men cleared out -- except one.

A sheeted figure was seen laying in a pool of blood. Medics removed his robe at Conway Hospital and noticed he was wearing his police uniform underneath the sheet.

James D. Johnston, a Conway police officer, was one of about 60 Ku Klux Klan members that attacked Charlie’s Place on August 26, 1950, emptying more than 500 rounds of ammunition into the club and injuring several people. Johnston died later that night and it is believed he was shot by another member of the Ku Klux Klan, according to statements made after the shooting from the Horry County sheriff.

“The club’s jukebox — the most powerful symbol of the cultural fusion that had united young blacks and whites in the postwar years — skipped, sputtered and went silent as it was riddled by a hail of bullets,” wrote Frank Beacham who authored a book on Charlie’s Place.

Earlier that night, a motorcade of about 40 cars, their passengers outfitted with white robes and hoods, made its way through the Hill. The lead car had a cross fastened to it’s bumper lit red with electric lights. The cars came and went on Carver Street before making their way north to Atlantic Beach, another all-Black neighborhood.

Charlie Fitzgerald, the club’s owner, called Myrtle Beach police.

If the Klan returned, he said, there would be bloodshed. Police passed the message along. The motorcade turned around after feeling Fitzgerald had made a threat.

Leroy Brunson remembers the night of the attack. Then 9 years old, he lived nearby and hid under the porch with his brother as the Klan opened fire. His mother grabbed the boys and ran into the woods to hide from the melee.

“People were running and hollering and screaming while they were shooting,” Brunson, now 79, recalled. “Then they took Charlie.”

Klansmen grabbed Fitzgerald who was outside the club with two guns ready to protect his property and clubgoers and threw him into the trunk of a car, according to archives.

Fitzgerald was dragged out of the trunk on the side of the road near highway 544. The Klansmen beat him and sliced his ear to mark him like an animal. The man making the mark was another police officer Fitzgerald told the Myrtle Beach police chief.

Fitzgerald escaped, dodging bullets as he ran. A friend brought him to the Myrtle Beach police department, not knowing the police chief, Carlise Newton, was one of the men in the car during the beating.

Three others were seriously injured including Cynthia Harrol, known as Shag. None of the clubgoers were killed in the attack.

The Klan didn’t go there to kill anybody, Beacham said, instead they were there “to kill the rise of Black music.”

Myrtle Beach’s wealthiest Black man

Fitzgerald was one of Myrtle Beach’s wealthiest Black residents. He ignored segregation laws and frequently visited whites-only businesses, where he was welcomed. Dino Thompson remembers eating with Fitzgerald at the Cozy Corner.

“He did not allow himself to be discriminated against,” Thompson, who is white, said. He remembered seeing Fitzgerald in the restaurant that was owned by Thompson’s father, a white immigrant, and other whites-only businesses.

His success eventually made him a target, but for almost 30 years the club operated as a melting pot for whites and Blacks.

The club would attract music lovers from all races and was also where many musicians spent the night while touring. Black artists such as Billie Holiday, Ray Charles and Otis Redding could perform at the whites-only clubs and hotels on Ocean Boulevard but couldn’t stay at them.

They found refuge in the motel rooms that sat on either side of Fitzgerald’s home on Carver Street.

The club was recognized as a safe place for Black people in the south in the Green Book, a guidebook for Black travelers. It was also part of the Chitlin’ Circuit, a list of performance venues where Black entertainers could perform.

“Charlie was a magnet,” said Roddy Brown who grew up next to the club. He remembers the posters Fitzgerald would hang all over town to announce a big-name artist coming to play. “When those music groups came in, people would flock to Myrtle Beach by the thousands,” Brown, 79, said.

The Hill was a booming all-Black neighborhood that included Charlie’s Place, Little Club Bamboo and the Patio Casino. It is now known as the Booker T. Washington neighborhood. Carver Street, the main artery that runs through the community, looks different now.

Following the klan attack, Fitzgerald was arrested and taken to an undisclosed jail, reportedly to keep him safe from Klansmen. Days later, Horry County Sheriff Earnest Sasser, a friend of Fitzgerald, gave a lengthy radio speech where he cleared Fitzgerald and other Black club go-ers of any wrongdoing.

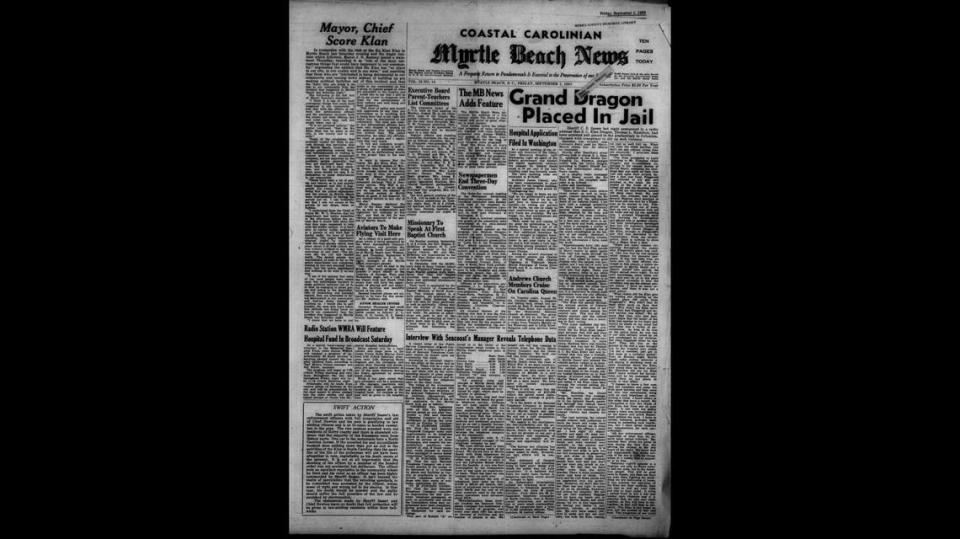

“No negro fired a shot...,” Sasser said in his speech that was also published in The Myrtle Beach News the week after the attack.

Fitzgerald eventually returned to the club after spending time in New York to recover. He continued to run the club until he died from cancer in 1955 at age 49.

The klan in Horry County

Both the mayor and sheriff at the time came out publicly against the attack. Mayor J.N. Ramsey told newspapers that the KKK “had no place in our city, our county and in our state.”

Sheriff Sasser blamed the attack and officer’s death on the klan, promising arrests but also warned against the integration that was going on at Charlie’s club.

“Whites would go to hear the orchestra and see the colored people dance,” the sheriff read on the radio. “I have, on many occasions, told them it is not a good policy.”

At least 15 klansmen were arrested in the coming months, including Grand Dragon Thomas Hamilton, who orchestrated the attack. They were charged with conspiracy to stir up mob violence. Some of the men had their cases dismissed before trial and the five remaining men, including Hamilton, were cleared of their crimes by an all-white jury.

Thurgood Marshall, at the time a special legal counsel to the NAACP, represented Fitzgerald during his dealings with the FBI. Marshall detailed the attack and subsequent arrests and FBI investigation in letters he shared within the NAACP.

Witnesses gave testimony of the attack but the FBI investigation yielded no results.

That November, the klan held a rally and cross-burning in Loris. They handed out pamphlets and invited the public to “hear the Klan side of the recent Myrtle Beach affair.”

By that time Hamilton’s charges had been dropped and he went after Sasser, eventually costing him his title. In the 1952 race for sheriff, Sasser was replaced by a Klan sympathizer. He lost all but four precincts, one of them was the all-Black Race Path community.

The music kept playing

After Fitzgerald died in 1955, his wife Sarah kept the club alive for about another decade. The bands kept coming and so did the dancers, white and Black.

Brown, whose father owned a business nearby, remembered seeing more mixing after the attack than before.

“The klan didn’t stop anything,” Brown remembered. “It was just one night of terror. The whites and Blacks still congregated together.”

The attack was the result of hatred and aimed at dividing the races. Thompson, who was allowed in the club despite his young age, said the opposite happened.

“It was one of the ugliest incidents we’ve had in Myrtle Beach,” said Thompson, who continued to go dancing at the club with his white friends following the shooting.

Both men still live nearby and worked on a project to save the club from demolition years after it shuttered in the 1960s. Sarah Fitzegerald died in 2009 at the age of 93. Her estate sold Charlie’s Place to the city of Myrtle Beach, which has been working to restore it for six years.

Legacy of Charlie’s Place

Seventy-one years later, there aren’t many people left who remember dancing at Charlie’s Place. Stories of the club and the attack have been passed down by word of mouth, in a documentary and books, but it wasn’t covered much by local newspapers and news organizations at the time.

Brunson remembers sneaking into the club because he was too young to enter. He worked with the Carver Street Economic Renaissance group to keep Charlie’s Place standing.

The Myrtle Beach Neighborhood Services Department has been working to restore the remaining structures which include one of the motel wings and Fitgerald’s home. The club and a second motel wing were unable to be salvaged.

The group is bringing in local businesses to set up offices in the former motel rooms and have converted most of the remaining space into a museum. City officials have applied to get Charlie’s Place on the list of historic places from the African American Civil Rights Network that is operated by the National Parks Service.

“Although this incident is not nationally known, such as the Rosa Parks story,” the application reads.”This violent episode and broader history of Charlie’s Place are important parts of the fabric of South Carolina’s civil rights tapestry.”