These nightclubs carved out a niche for Fort Worth teens in the 1970s, then faded away

Teen nightclubs were something new on the local music scene in the 1970s.

A new group of nightclubs got around issues with the legal drinking age in a couple of ways. One was by separating the room into legal drinking customers and underage customers. Another way was to not enforce the law too strictly. Since police officers were not a regular presence at these places, there was only “club security” (the bouncer) to get past, and looking older, having a friend on the door, or being cute (girls) got you admission, no questions asked.

Before the 1970s, nightclubs were divided into hotel bars and cocktail lounges, both of which catered to an older crowd.

Then there were the country music venues like Roundup Inn and Panther Hall that catered to the boot-scootin’ crowd. Not too teen friendly either.

All that changed in 1970 when the Speakeasy (originally the “Speak-Easy”) opened at 6399 Camp Bowie in a space formerly occupied by the Terpsichorean Club. The decor hearkened back to the glorious Roaring Twenties, but the music was all ‘60s: rock, psychedelia, British Invasion cover bands. The new owners were Dennis and Ray Beard and Beverly Robeson. The club catered to a well-heeled, west-side, university crowd.

Constantly chasing after the elusive full house, in the late ‘70s the Speakeasy began catering to the Country-Western crowd by booking Larry Mahan and Mickey Gilley.

I Gotcha nightclub, which had the same Camp Bowie address, aimed to attract the hip, young rock ‘n’ roll crowd. It struggled to pack the house before becoming Phase III in 1978, advertising “three clubs [rooms] for the price of one” featuring three bands.

In 1970, Ed Willians opened the Ginger-Bred House at 5428 Calmont, right off Camp Bowie and also catering to a younger, well-heeled audience. The Calmont location had a history of failed nightclubs, but the Ginger-Bred House promised “wall-to-wall young mods gyrating to [loud] rock music.” One advantage it had over other clubs is it had a house band, also known as Ginger-Bred, managed by Williams. They were slickly professional and performed nightly when they weren’t on the road.

Unfortunately, Ginger-Bred House was removed from the scene in 1973 when expansion of the West Freeway took the property.

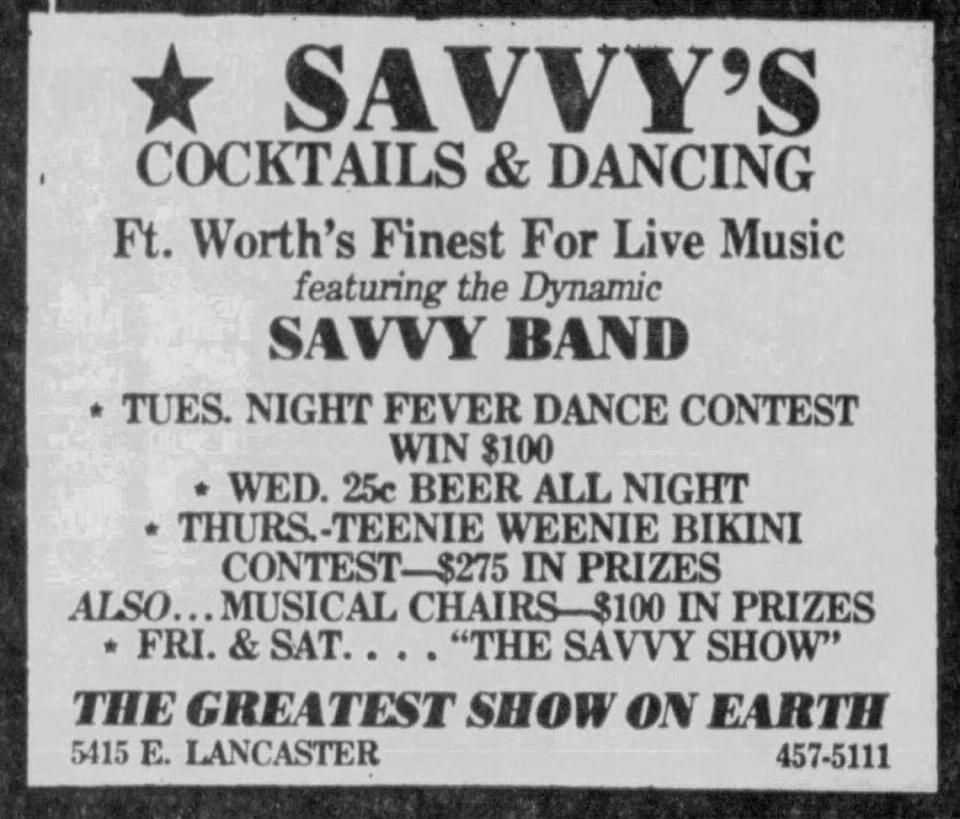

On the east side of town, catering to a different clientele, were Savvy’s (5415 E. Lancaster) and Electric Circus (3140 S. Riverside Drive). Savvy opened in 1977, offering live music nightly performed by the house band, Savvy. They also had dance contests with prizes, 25-cent beer, and admitted “unescorted women” free.

Electric Circus, with a name borrowed from Manhattan’s famed discotheque, was a Black club that attracted, whether legally or illegally, young people from Dunbar High School and Tarrant County Junior College. Its location in a strip shopping center was anything but glamorous.

The music was Top 40 hits played by a disc jockey. Their quirky addition was having two drummers back up the records. Electric Circus relied on a Plexiglass barrier and its cocktail waitresses to enforce a line separating “adults” from “teenagers.”

Police were frequently called to the Electric Circus after it opened in 1970. The violence came to a head in October 1971, when a fight broke out and spilled into the parking lot. Police arrived and apparently walked into an ambush. Two officers were shot, one of whom died. After that, the crowds stayed away, and the Electric Circus soon closed.

It was Spencer Taylor who put his mark on the nightclub scene in the 1970s by opening three clubs on University Drive that catered to the TCU and Paschal High School crowd (the latter unofficially). Taylor had attended Arlington State College and briefly worked as a golf pro and a car dealer before spreading his wings. He invested everything he had or could borrow to open a string of nightclubs.

Taylor’s first nightclub was Spencer’s Corner, which moved into the former Fat Albert’s nightclub right across from the TCU campus. His target clientele was the “youthful, rock ‘n’ roll set.” Besides “live rock music,” the club also attracted customers by allowing “unescorted women” in free. TCU coeds came in bunches from the dorms right across the street, and the boys followed.

Taylor followed his first club with the Daily Double, which opened in the former 1849 Village in a space formerly occupied by an ice cream parlor. The Daily Double aimed to attract a “slightly older” crowd. Last came Spencer’s Palace, which moved into the building formerly occupied by the Farmer’s Daughter steakhouse. Each club attracted up to 1,000 paying customers on a good weekend. Paschal students found it easier to get into Spencer’s Corner than the other two, although they were liable to be “carded” at any of the clubs.

Taylor’s business honeymoon came to an end in 1979 when a series of sexual assaults were reported outside his clubs. He beefed up security but that was followed by Black club-goers complaining of discrimination at the Daily Double and Spencer’s Palace. They cited the fact that they were required to show two forms of identification to get in (white people only had to show one), and they were turned away because they didn’t’ have “reservations.”

The complaints went public when Municipal Court Judge Maryellen Hicks recused herself because she was Black and hearing the case might look like a conflict of interest. That did not keep her from blasting the clubs and their ownership. Taylor vehemently denied the discrimination. The furor died down, and he went on to bigger and better things, opening Billy Bob’s Texas in 1981.

Rock music ruled through the 1970s. The Speakeasy, Ginger-Bred House and other clubs booked local talent like The Barons and Courtship, who were good enough to get recording contracts. The Speakeasy also booked Razzy Bailey, an MGM recording artist with two charting records, “I Hate Hate” (1974) and “9,999,999 Tears” (1976).

Nightclubs like I Gotcha and the Speakeasy during their heyday cultivated an image as “the place to go” for young singles. It wasn’t “happy hour” they offered; it was the party vibe. The disco was the teen scene, and movies like “Saturday Night Fever” (1977) reinforced that appeal.

The clubs faded from the scene in the 1980s for several reasons. For one, law enforcement began cracking down on the easy-admission policy, forcing club management to seriously check IDs before letting anyone in. Secondly, the charade of separating patrons into an adult section and a teen section no longer worked. Also, hiring good rock acts had become a more expensive and difficult proposition, only somewhat alleviated by changing musical tastes.

“Urban Cowboy” style country music pushed out the garage bands of the ‘60s. In 1987, Savvy switched to all-country music, six nights a week. Kept out of the clubs now, teens began “cruising the strip” on Camp Bowie and West Berry, congregating in parking lots to socialize and drink.

The teen scene died a slow death. I Gotcha tried to reopen in 1983, offering both rock and country music (different rooms) on the same night and extending happy hour to happy hours.

Another blast from the past came when the former house band Ginger-Bred reunited in 1993 and began playing local gigs. Now all those former teenagers who used to slip into the Ginger-Bred House could pay their money to hear the band play without being carded. Sadly, the talent was still there but the audience wasn’t.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.