'Nightmare': How Category 5 Hurricane Otis shocked forecasters and slammed a major city

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

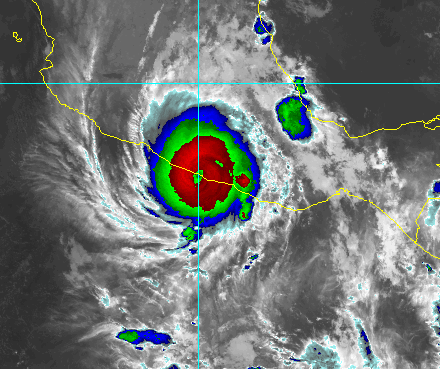

Hurricane Otis shocked even experts with its surprising explosion from a tropical storm to a Category 5 hurricane in just 12 hours last week as it approached Acapulco, Mexico and made landfall on Oct. 25. The storm killed at least 46 people and caused billions in damage.

Its unexpected and extreme transition from 70 mph winds to 165 mph winds raises crucial questions about how forecast models flubbed, the increasing risk of hurricanes rapidly intensifying into major storms more often, the degree to which global warming is fueling that intensification and what all of this means for millions in hurricane-prone regions.

In an era when potential tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean attract headlines even as they depart western Africa, Otis did the unthinkable. The tiny but devastating storm slammed into Mexico's Pacific Coast with little warning that it would bring some of the highest winds in the country's history.

The storm's high winds – with gusts of up to more than 180 mph – damaged more than 220,000 structures, especially high-rises, the Associated Press reported. After the storm, the city was cut off for more than a day, AP reported, in part, because the lack of warning prevented officials from pre-staging resources.

Less than 12 hours warning for a storm of such magnitude is “a nightmare,” said Kerry Emanuel, a meteorologist and climate scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"It’s a perfect storm of a problem," Emanuel said. "If the atmosphere had been slightly different, this would have never happened. We would have had a tropical storm that wouldn't have been a big deal."

It's a problem many meteorologists and climate scientists say is happening more often in the warming world.

How the National Hurricane Center forecast evolved

At 10 p.m. on Oct. 23, Tropical Storm Otis had 50 mph winds, with features that could be associated with a rapid intensification in wind speeds but computer models didn't indicate it would happen.

By 4 a.m., winds were up to 65 mph. Wind shear had decreased and one model showed a 1 in 4 chance of rapid strengthening over 24 hours. The official forecast – warning the storm was likely to become a hurricane and strengthen before landfall – was still outside the guidance from the center’s most reliable models, wrote the author of that forecast, Daniel Brown.

At 10 a.m. on Oct. 24, the center warned further upward adjustments in intensity were possible, but the incredible transition over the next 13 hours took everyone by surprise.

◾ 1 p.m. – Otis reached hurricane strength with 80 mph winds.

◾ 2 p.m. – The center had its first and only reports from an Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunter aircraft, which provided key information and warned Otis was almost a major hurricane with winds near 110 mph.

◾ 10 p.m. – The winds had reached almost 160 mph, a catastrophic Category 5 hurricane.

◾ 11 p.m. – Otis neared the busy tourist region known as Mexico’s Riviera with deadly 165 mph sustained winds and higher gusts.

Around 1:25 p.m. Otis slammed into the coast, its diminutive size both a blessing and a curse. It was easier for the storm to rapidly intensify in the exceptionally warm waters offshore but it curtailed the reach of the extreme winds that pummeled buildings and whipped up a storm surge that battered the coast.

Analyzing the storm

Hundreds of other storms with forecasts similar to Otis ”didn’t do what Otis did, so the question is what happened?” asked Clark Evans, a hurricane model expert, professor and chair of atmospheric sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “None of the field’s state-of-the-art guidance suggested anything close to what occurred was even possible."

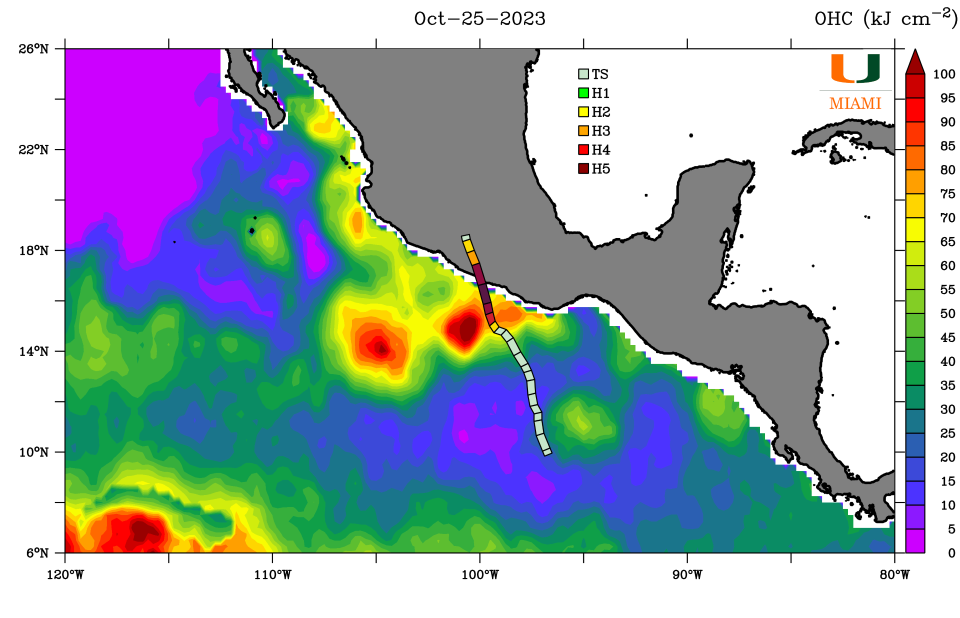

The hurricane center, as well as the research and modeling communities, will study Otis for months to come. Several factors may have contributed, including warmer than normal waters and upper level winds.

It didn't help that the hurricane models had less data available than with Atlantic storms, where repeated hurricane hunter flights take place, with additional information from the dropsondes and drones the flights deploy, as well as a more dense network of weather buoys and land-based radars.

Hurricane hunter reconnaissance flights aren’t typically sent into tropical storms in the Pacific, Brown said. It’s a long trip and the aircraft don’t have preestablished staging locations like they do in the Caribbean.

As a regional meteorological center, the hurricane center names and forecasts tropical cyclones for 29 countries across the Caribbean, Central America and the northern shores of South America under an agreement with the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations. Individual countries are responsible for distributing the forecasts to their residents and visitors, however the U.S. has agreed to that responsibility for Haiti.

What is rapid intensification?

Rapid intensity is defined as an increase of at least 35 mph in wind speeds over 24 hours. Otis experienced nearly three times that. Forecasters look for signals of rapid intensification in a storm’s structure, and the surrounding environment, but it can be difficult to forecast the timing and magnitude of such strengthening, Brown said.

All of the Category 4 and 5 storms that struck the U.S. over the past 100 years were tropical storms just three days before landfall, and all went through rapid strengthening within roughly 50 hours of landfall, he said. "Andrew, Charley, Michael, Ida and Ian are all on that list."

More than half of all the hurricanes with winds of more than 150 mph to make landfall in the United States over more than 100 years occurred in the last 19.

Why does warmer water produce stronger storms?

The ocean Otis moved over was “exceptionally warm,” with surface temperatures in the mid-80s, up to 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than normal for this time of year, Evans said. Under the right conditions with winds and moisture, water temperatures were “more than sufficient to support a hurricane of category 5 intensity.”

Warm water is to hurricanes as dry brush is to a wildfire, a key source of fuel and energy.

"Think of it like your morning cup of coffee – for a hurricane, warm ocean waters act like the caffeine in our morning coffee that helps get us going," said Andra Garner, a climate scientist at Rowan University in New Jersey. Abnormally warm ocean water is "kind of like an extra shot of caffeine in the coffee, providing lots of energy for the storm."

Emanuel says it's possible water temperatures in the ocean just beneath the surface also may have played a role. Because the Pacific has more fresh water, which is lighter than saltier water, he said, it's possible Otis was churning up hotter water from below, which would let the storm intensify at the maximum possible rate.

Is climate change causing storms like Otis to rapidly intensify?

Though hurricane experts and climate scientists debate whether any individual storm can be linked to climate change, many say the warming climate is contributing to warmer ocean temperatures, such as the unprecedented ocean heat waves this summer, and to the rapid intensification of storms like Otis.

Several peer-reviewed studies have shown evidence of an increasing probability of such events, and that these storms have a human-induced fingerprint on them, said Jim Kossin, a science adviser to the First Street Foundation who has studied storms for decades.

“There is no question that ocean temperatures have increased due to global warming, and there is no question that this warming allows hurricanes to get stronger and to rapidly intensify,” Kossin told USA TODAY. Scientists are more confident that events like Otis' rapid intensification become more likely under climate change, he said.

The world's oceans have absorbed about 90% of the excess warming that has occurred due to human-caused climate change, and the global average sea surface temperature has risen by more than one degree Fahrenheit since the 1980s, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

That same report projected with "high confidence" that the proportion of tropical cyclones that reach Category 4 and 5 levels around the globe would increase with climate warming.

In the Atlantic, five storms underwent rapid intensification in 2021, and three this year – Franklin, Idalia and Lee. In the eastern Pacific, Hurricane Patricia broke records in 2015 for rapid intensification. Otis broke that record.

Hurricanes and climate change Is climate change fueling massive hurricanes in the Atlantic? Here's what science says.

A recent study led by Garner concluded Atlantic hurricanes are now more than twice as likely as before to rapidly intensify from minor hurricanes to powerful and catastrophic.

While her work focused on the Atlantic, Garner said certain physical factors "are very favorable for hurricane formation, regardless of where you are in the world." Warm ocean waters are one of those factors.

"I think what we saw with Hurricane Otis lines up pretty well with what my research suggests that we might expect in a warmer climate," Garner said. "That increased heat in our oceans is energy for storms, and it has the potential to allow storms to strengthen more quickly than they might have with cooler ocean temperatures in the past."

However, both Emanuel and Tom Knutson, a climate scientist with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, said more research is needed to determine how much human-related changes in greenhouse gases and aerosols may be contributing to the intensification of Atlantic hurricanes.

What's the takeaway?

"Otis illustrates why people in hurricane prone areas need to be vigilant and also prepared,” Brown said. It’s important to keep supplies on hand throughout hurricane season and have a plan for what you will do if a hurricane approaches, he said. "You can act much faster when there’s a threat."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hurricane Otis shocked forecasters with Category 5 Acapulco landfall