A 'nightmare' scenario on the rise with coronavirus: Dying alone

Deborah Mastromano’s mother was dying, isolated inside a Long Island nursing home that had been beset by the coronavirus. But she couldn’t get anyone to pick up the phone.

Mastromano called the nursing desk. She called a supervisor. She called a nursing assistant. One staff member answered late last Saturday but quickly ended the call. “I can’t talk right now,” the woman said, before hanging up.

Mastromano, 67, knew the workers were stretched thin. It had been nearly a month since the home for seniors in Brentwood, New York, had banned visitors, hoping to prevent the spread of the coronavirus among its frail residents. But the virus found its way in anyway, and now nurses were scrambling to care for the sick.

Mastromano’s mother, Betty Coleman, 88, wasn’t among those infected, but her health was declining. Coleman had been in hospice care since July, suffering from dementia, lung cancer and heart disease.

Finally, late Sunday, Mastromano got her mother’s doctor on the phone. He gave a distressing update. Coleman appeared to be fading rapidly and was now “actively dying” — a phrase physicians use to describe a patient who has only hours or days to live.

Her mother hadn’t been eating or drinking, the doctor explained. And earlier that day, staff had found her in bed, half-conscious, faintly calling for her only daughter, who prior to the pandemic had always visited three or four times a day.

“Debbie ... Debbie ... Debbie ...”

Mastromano cried and pleaded. “Let me come see her,” she said.

The doctor said he wasn’t sure if that was possible. But he would try.

As the coronavirus sweeps the nation, infecting and killing thousands, hospital and nursing home policies intended to slow its spread are blocking people from being at the bedside of dying loved ones. In some instances, the virus has devastated otherwise healthy people, forcing families to grapple with difficult end-of-life conversations far sooner than expected, and remotely. For others, like Mastromano and her mother, the crisis is complicating an end-of-life process that’s been in motion for months or years.

In New York, where intensive care units are packed with coronavirus patients, most visitors are prohibited. Some nurses say they’ve tried to make time to hold patients’ hands in their final hours, but overworked medical staff can’t sit vigil, and as a result, some patients are dying with no one at their side.

In other places, hospitals and nursing homes are allowing one or two visitors — but only once a patient is actively dying. That means some families must decide whether a patient’s spouse or child gets to put on a medical gown and a plastic face shield to say goodbye in person. With gloves on, they can hold the patient’s hand or touch their cheek, but they can’t kiss them, feel their skin or snuggle next to them in bed.

These final moments are crucial, not only for the dying, but for the family members they leave behind, said Dr. Sandra Gomez, a palliative care physician in Houston who has spent her career coaching family members on how to interact with loved ones as they die.

“As a clinician, what I’ve learned is that family presence at the end of life is very healing for the family,” Gomez said. “And for the patients, it’s often a time to be a catalyst for reconciliation and a catalyst for forgiveness.”

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Last month, Gomez’s 72-year-old father tested positive for the coronavirus, one of the earliest confirmed cases in Texas, and although he’d been in fine health before then, he had to be hospitalized. His condition deteriorated rapidly, Gomez said, and soon she was forced to put her end-of-life teachings to the test.

She was more fortunate than many, she said. The hospital allowed her to put on a gown and a mask and spend time with her father in the intensive care unit before he died.

“I asked him why it had to be him,” Gomez said, crying. “The guy never won the lottery for anything else. In my heart, I felt him say, ‘I have work to do. And so do you.’ And that brought me peace.”

She would have been heartbroken, Gomez said, if she hadn’t got that time with him.

‘I never said goodbye’

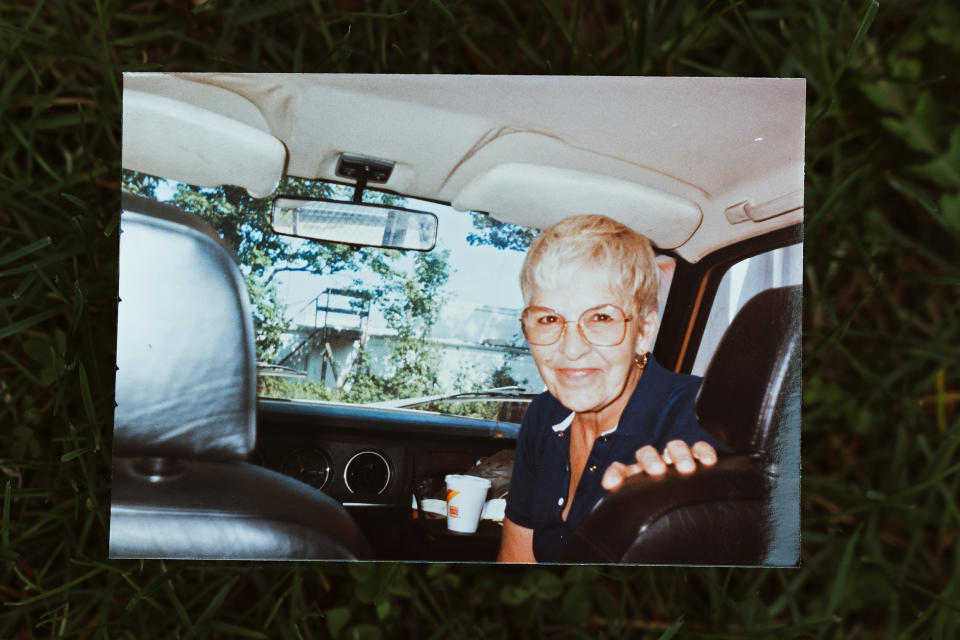

Mastromano never wanted to move her mother into a nursing home. For more than two decades, Coleman lived downstairs from her. Each morning before Mastromano left for work, her mom would hand her a cup of coffee and tell her she loved her.

“We were buds,” Mastromano said. “I loved having her close.”

But last year, Coleman’s radiation treatments for lung cancer left her weak and struggling with heart failure. Mastromano had retired from her job as a court clerk in Nassau County four years earlier to care for her mother full time, but as Coleman’s health spiraled and her dementia worsened, it became too much for her daughter to handle.

Mastromano found a senior home just a few minutes away, a skilled nursing facility called Maria Regina Residence, and in July, her mother moved in. Mastromano was there for every meal and returned each night to help her mom calm down before bed. In the evenings, even with medication, Coleman’s dementia sometimes made her hallucinate, Mastromano said. Some nights, she believed she’d been set on fire. Other times, she thought she was being raped.

“This has been a nightmare,” Mastromano said. “Each day is different, and each moment in time is different to her mind. At least sometimes, when she held my hand, she felt comfort.”

But then, on March 12, Mastromano learned that the nursing home — like thousands of others across the country — was suspending visiting hours in the hopes of preventing a coronavirus outbreak among vulnerable residents. Initially, the staff assured Mastromano that the restrictions wouldn’t apply to her because her mother was in hospice. But when she came to see her mother the next day, a nursing supervisor stopped her.

“Oh, no,” Mastromano remembered the woman telling her. “Betty Coleman is not actively dying.”

Mastromano said she got upset.

“You realize that I never said goodbye,” she remembers saying. “I will probably never see her again.”

Brenda Burton, administrator for Maria Regina Residence, said it was difficult when state health officials mandated visitor restrictions at nursing homes last month, but the center’s priority is protecting its elderly residents.

“The importance of families and visitors to our residents cannot be quantified,” Burton said in a statement. “They are essential to the social well-being of our residents and they are our partners in care. We monitor our residents daily not only for their physical health, but for their emotional health.”

At the urging of nursing home staff, Mastromano bought a tablet so that her mother, who is legally blind, could video chat with her once a day. But the arrangement proved difficult.

“For the first week or so, it was not terrible,” Mastromano said. “She didn’t quite understand what was going on, but she could hear me and I could talk to her. But then Mom started getting more and more confused by it.”

Their struggle highlights how, despite well-meaning campaigns calling for the public to donate devices to hospitals hit hard by the coronavirus, saying goodbye via an iPad is a complicated substitute for being at someone’s bedside. In many cases, dying patients are unconscious or sedated, with a ventilator tube in their airway. Some have neurodegenerative disorders, making it difficult or impossible to communicate via video feed.

“They can’t talk and are basically comatose. In those cases, FaceTime is pretty pointless, although you can at least show the family member that their loved one is comfortable” said Dr. J. Randall Curtis, a palliative care physician in Seattle, who has conducted research on what makes for a good end-of-life experience.

Since most volunteers, medical students and family members have been banned from hospitals and hospices, digital goodbyes also create additional tasks for overworked health care workers. Who is going to hold the device or answer calls?

Even after several attempts went poorly, Mastromano wanted to keep trying. She was desperate to see her mother each day.

But after the nursing home’s first confirmed coronavirus case a couple weeks ago, it seemed like staff became too busy to set up the tablet for her mother, Mastromano said. Even phone calls became unworkable. A nursing aide would hand her mother the phone, then walk away.

Her mother kept losing her grip or holding the device upside down. Mastromano would sit on the line, sometimes for 20 or 30 minutes, listening to her mother scream.

She could tell from the sound of her voice, her mom was losing her strength.

“What I really needed,” Mastromano said, “was to hold her hand.”

Comforting the dying

People have been dying alone long before the coronavirus, though not usually so often. Some have no close friends or families. Others live far from family. In those cases, patients or loved ones can request a volunteer from an organization called No One Dies Alone to sit with them during their last moments.

When a patient is near death, the program’s volunteers — including medical students and spiritual care practitioners — take turns spending a few hours by their bedside. They might talk or read to them, light candles, play music and mop their brow.

“Being with someone when they die is a very intimate space. It’s like being the best man at someone’s wedding or being at the birth of someone’s child,” said Jared Raikin, a second year medical student at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College in Philadelphia, and a volunteer with the group.

But in mid-March, all No One Dies Alone programs across the United States were halted in an effort to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, keep volunteers safe, and avoid wasting medical masks, gloves and gowns, which have been in short supply nationally. It’s a huge blow to the volunteers, and to the growing number of ailing patients in need of their kindness.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Raikin said. “One of the main goals of the organization is to minimize the number of patients who need to die alone, but it’s growing and growing and growing, and there isn’t a lot we can do about it.”

In addition to providing emotional support, these volunteers look for signs of discomfort, such as grimacing or labored breathing. Melissa Helmkamp, 37, a stay-at-home mom and No One Dies Alone volunteer from St. Louis, Missouri, has had to call nurses for more pain relief for about half of the dying patients she has sat with.

“I had one patient who actually woke up and was very afraid,” Helmkamp said. “She was asking, ‘Help, help, help,’ and we had to get her medicine adjusted immediately. If nobody was there, the patient would have likely fallen out of bed.”

Dr. Wesley Ely, a critical care physician who works with geriatric patients at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said one of the most important aspects of his job is comforting people as they die. That means sitting with them, holding their hand and asking them what they loved most about life.

Before the pandemic, he would sometimes offer dying patients a spoonful of honey, a small gesture, he said, “just to demonstrate love and affection and something very human.”

“When you are dying, honey is so uncomplicated. They can’t aspirate on it. It tastes sweet and there is this human-to-human connection,” Ely said. “There’s no honey on a spoon now, and that’s tremendously heartbreaking. It’s all you had to offer this dying person, and now that’s gone.”

Final moments

Mastromano cried in bed last Sunday night after the doctor told her that her mother was fading. The next morning, she got a call from one of the nurses.

“She said, ‘I don't like the way this looks, Debbie. I want you to get down here,’” Mastromano said.

Nursing home officials had determined that her mother was now close enough to death to allow her to visit for one hour each day. Mastromano drove straight over. She put on a gown, gloves and a mask. A nurse's aide escorted her into her mother’s room.

“Mom, it's me,” she said. “They let me come.”

Her mother didn’t look like she did a month earlier. She was thinner and pale. She was on her side, breathing heavily and moaning. Mastromano noticed a new lump on her neck. She didn’t seem fully conscious.

Mastromano wished she could have been there during those last few weeks. How many nights had her mom screamed herself to sleep? Did she understand why her daughter had stopped coming? Was she scared?

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Mastromano sat next to her mother and held her hand. She put a cool, damp cloth over her forehead and told her that her grandsons missed her. That she was sorry for losing her temper sometimes, back when her mother’s dementia started to get bad. That she was proud of her for the life that she’d led.

Coleman — the daughter of German immigrants and a single mother of two — had done her best to raise her children working as a bookkeeper and receptionist, Mastromano said. She loved jazz music, Frank Sinatra and animals. She’d been an atheist most of her life, but in recent years, after her son died, she’d started going to church with Mastromano and was baptized.

“Mom, you’re going to heaven,” Mastromano told her. “You’ll be free of pain and you’ll be able to dance again.”

“Mom, do you love me?” Mastromano asked, and a moment later, felt a gentle squeeze on her hand.

Then, far too quickly, time was up. A worker showed up at the door to escort Mastromano away.

“I love you, Mom,” she said, as she backed out the door.

“I’ll be back tomorrow.”

Mastromano did return the next day, not to hold her mother’s hand or pray with her — but to view her body before it was sent to the mortuary.

She figures she'll have her mom cremated. Until the pandemic passes, she won't be able to plan a funeral.