“It Was All About the Nights”—Max Mara’s Ian Griffiths on the Club Kid Life of 1980s Manchester

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nostalgia’s not my thing, but making connections between past and present is. Right now the early 1980s have a strong pull on me (and not just because it gives me an excuse to look at images of Robert Smith). My current journey back to the ’80s began with a hint of New Romanticism wafting around the fall 2021 collections. It was most resonant in London, especially at Matty Bovan’s dramatic wind- and sea-swept collection for fall 2021. Then came the sad news that Nick Kamen had died, and I came across a photo of him walking in Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s history-making Pirates collection circa 1981, the same year as the Royal Wedding. Combined, these two events seemed like watching pages from fairy-tales come to life.

Wanting to know more, I contacted my swashbuckling colleague Luke Leitch to talk about the New Romantics and he put me on to Ian Griffiths, the British-born creative director for Max Mara, a former club kid. Here, he shares the ups and downs of swanning around Manchester in the 1980s in wedding attire and mucho makeup.

How did you come to dedicate your life to clubbing?

I was born close to Windsor in Berkshire in the south of England, and then I was brought up for a short while in Manchester, but we moved to Derbyshire [and] that’s where most of my childhood was spent. Having failed my Cambridge entrance exams, I went back to Manchester, to study architecture. That was 1979, and it was just at the height of Manchester’s cultural, creative youth [and] musical explosion. The big band at the time was Joy Division. I used to go and see [them] two or three times a week.

Photo of Peter HOOK and Ian CURTIS and JOY DIVISION

There used to be a club called the PSV, which was a kind of bus conductors and drivers social club in the middle of this terrible run-down council estate—council in the UK means like public housing—where most of us lived. One night a week that became the precursor to what eventually became the Hacienda.

STOCK

In the midst of this really rundown and deprived inner city at a time when, if you weren’t a student—and once I dropped out of college I wasn’t—you were living on unemployment benefits, in absolute grinding poverty, we developed this kind of cult of dressing up. It was all about self image and nothing else really at all. Well, not nothing else, but it was mostly about self image.

Everyone knew that you were a kid who lived on a council state, [who] probably didn’t have a job. And in your own mind, and everyone else’s mind, probably didn’t have any kind of future at all. Everyone knew who you were, and that didn’t matter, it’s who you could appear to be for that night at a club.

Can you give some examples of the styles you were into?

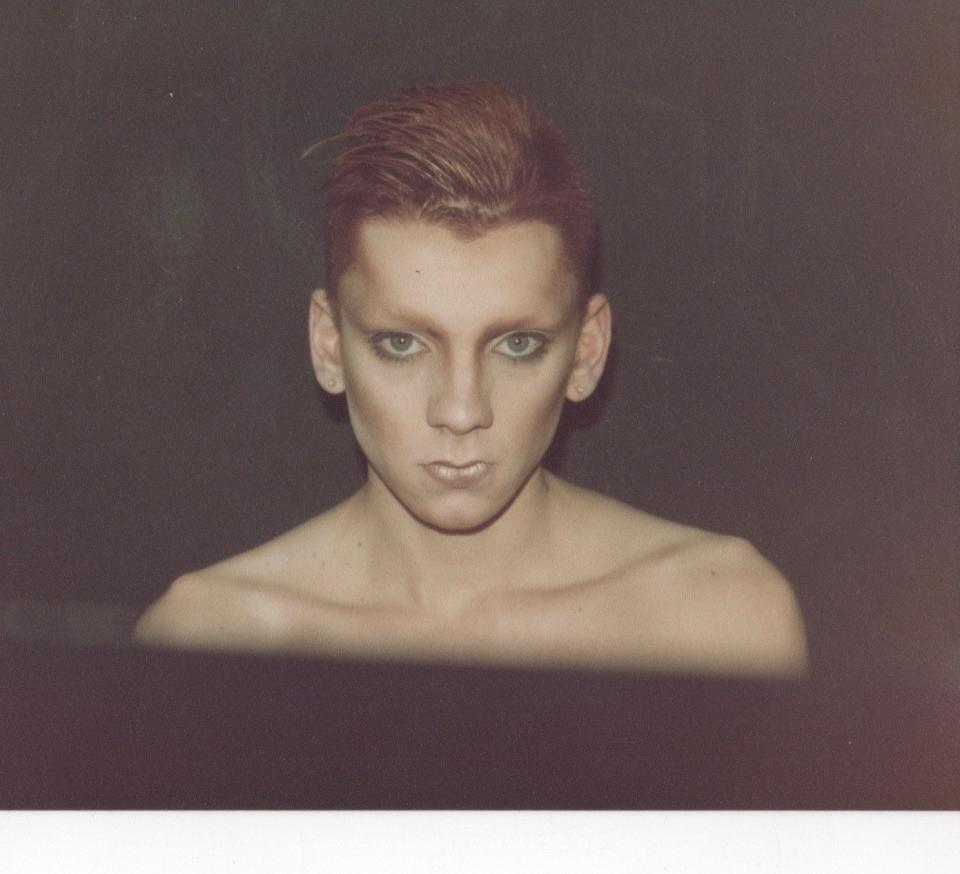

In 1979, 1980 [PSV] was all very postpunk. There was, Joy Division, The Durutti Column, A Certain Ratio and all those quite serious Manchester bands, and the look was very kind of postunk/David Bowie, Berlin. Berlin was like our Mecca. None of us had really been there, but we imagined being in Berlin.

So that kind of Bowie look, with the military trench, and the homburg or the fedora, and the hennaed hair, was the kind of most flamboyant look at that time. And then in 1980, something happened.

It was looking back in a sense to something that had happened a few years previously, which was the glam rock, Roxy Music, glam rock. There had always been fans of David Bowie who wore lots of makeup and so on, but in 1980 it turned into something amazing. It just happened over a period of a few weeks, and it kind of sprouted all over the UK. It was January 1980 when it really started to happen and Ultravox came out with Vienna.

People started dressing up in the most flamboyant way, [it was] escapism, sheer escapism. On a personal level [it] coincided with me just about flunking my university course and dedicating my life to clubbing.

What was the rhythm of your days?

Someone asked me recently, ‘Could you describe Manchester days and Manchester nights?’ And my answer was, ‘Well, the days were spent but waiting for the nights, it was all about nights.’

I started to commandeer a friend’s domestic sewing machine, and taught myself how to use it, badly. [I] used to buy lining materials or sari fabrics from the Indian shops; these fabrics which cost nothing at all, but were very, very flamboyant and very bright. We started making ourselves really kind of like peacock costumes, and it all became about going out and posing. Costumes, hair, makeup: a complete triumph of image, if you like.

It was completely non-establishment in the sense that the normal news, fashion media, major music entities, had no part in it at all. It was a time when the culture was being made by the kids that were living it. I think that was what was one of the most special things about it, that it was a self-generated, sort of self-owned culture.

When you went through all that effort to dress up—you’d spend an hour making your costume out of lining material, but you’d spend the rest of the time doing your makeup—when you’d got yourself together and finally appeared at wherever you were going, you were doing it for the people who were present at the time. It’s so different to how [it] would be today, because you would be doing it for everybody who wasn’t there today. At the time you were doing it for everybody who was. And the chances are that the only people who would see you would be other people who were present, so it was for a very, very limited group of people who all knew each other.

Did you call yourselves New Romantics?

When the term new romantic started to be bandied about we were constantly looking for other ways of describing ourselves,like peacock punks, but they all sounded either just as pretentious or banal. I never saw the ‘New Romantic’ thing as a thing, if you know what I mean. We tended to regard the NR tag as being almost mainstream. We were part of very fluid sub cultural network where punks, Bowie devotees, glamsters, rockabillies, even skinheads came together. I never thought about it as a rejection of punk, in the way that punk was a complete rejection of hippy-ism. It was just about self-image.

We were all parts of a group that defined itself as other, and people could move quite fluidly from one to the other. We styled ourselves, we did our own makeup, our own hair. We did look slightly look down on people who had to buy their clothes. We even slightly looked down on people who had to buy things like Westwood, because to us it had greater value to be making your own culture. I never really did the straight-down-the-line pirate look because Vivienne Westwood was doing it, and we wouldn’t wear anything that looked like you could have bought it; not that any of us Manchester club kids could have afforded it anyway.

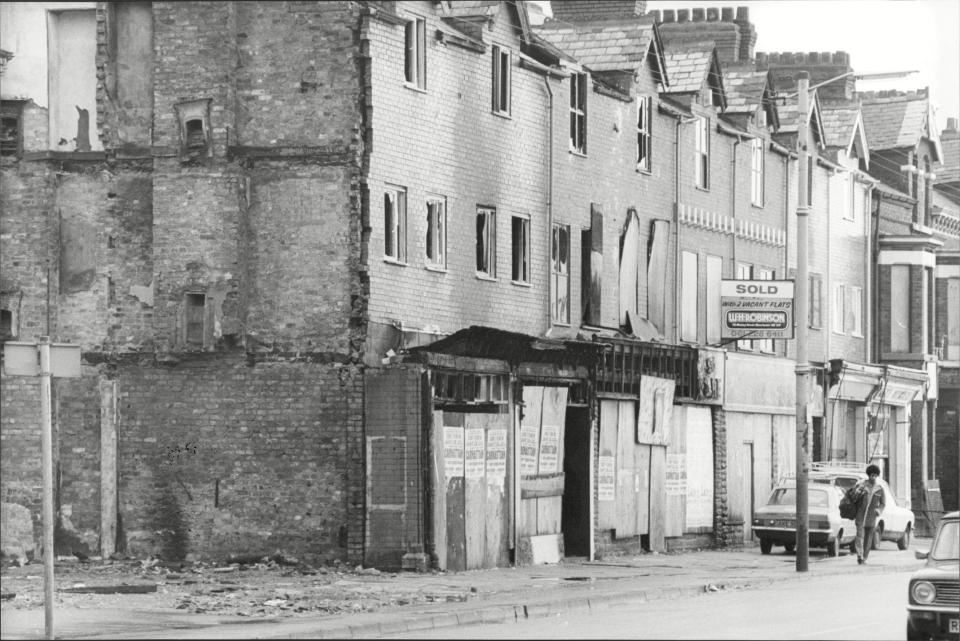

Hulme Crescents

Was the club scene a reaction to what was happening in the world?

We lived in an atmosphere where we didn’t really feel we had any kind of future. It was Thatcherite Britain, just as Margaret Thatcher was really getting to grips with her premiership and at the height of her powers. The whole climate in the UK was one of making young people, creative people, people that didn’t quite fit into the mold, feel that there was no place for them at all. That’s one of the reasons why I so lightly gave up my university course, because I thought that there would be no future for me. I don’t think any of us really looked ahead to having much of a future. So in that sense, we didn’t look on what we were doing as being a thing that would have any lasting meaning beyond the time we were doing it. Now look at it, we’re still talking about it 40 years later!

Shops Still Shuttered Up After The Summer Riots In Moss Side Manchester.

I think it’s probably quite well documented that Margaret Thatcher’s intention was to shut down whole industries and they were based in the north of England. So towns like Manchester and Sheffield really suffered huge deprivation. The Specials had a song which summed up that time for young people, “Ghost Town,” which describes unemployed kids, with no hope, living in rundown half, abandoned Northern cities. 1979 and 1980 were characterized by miner’s strikes and by the urban riots too. I was stuck in my flat for a week with this raging battle going on around me, unable to go anywhere. There were literally pitch battles happening in the streets below. So it was a time of great poverty, deprivation, tension. And [we were dedicated] to partying in the middle of it all.

What role, if any, did class play in all of this?

I can say that it was classless. It didn’t matter because you’re in that scene and you’ve chosen to be. We rejected the whole class thing. And in a sense, wherever we came from, we sort of thought we were above it all, because we’d turned our back on it and we didn’t want to engage in it at all.

I personally come from a very middle-class kind of background, which I had at the time turned like my back on and rejected. People judged you entirely by the image that you created for yourself, I think genuinely. You didn’t feel superior to somebody you who had a different sort of class background to you. It all relied on completely rejecting whatever social class you came from; and you know, that’s really something for the UK, [because] the concept of class is pretty much ingrained in our social interactions.

What did the local non-clubbers make of all this? Was it safe to walk around all dolled up?

It wasn’t all happiness and fun; it was quite a dangerous life that we’d chosen for ourselves. I was mugged any number of types and also beaten up, you know queer-bashed, more than once. Verbal abuse and physical abuse was, was a part of daily life. I used to walk around Manchester wearing my wedding veil, which was good for hiding bad makeup or not being dressed. perfectly underneath; that was my day look.

I finished up in hospital on a few occasions. In fact, on one occasion I was not admitted to hospital. I was sent home and told, ‘What do you expect? If you dress that way, this is what will happen to you.’ So you attracted a lot of very negative attention, but that created a sense of camaraderie. There are some very, very painful memories too, from that time. It wasn’t all fun, at all, but it seemed—I don’t know—a fair price to pay.

Would you describe this violence as stemming from homophobia?

A great deal of it was homophobia. I think a lot of mainstream masculine culture associated anything to do with dressing up, fantasy, hair. and makeup with, homosexual behavior. And you know, lots of us were gay—but not all of us by any means. The great irony is that we used to run the risk of getting beaten up, queer-bashed, but the last thing on our minds with all these flamboyant costumes was, if you like, sex. It wasn’t done for that. It wasn’t done for the purposes of sexual attraction at all. And sex wasn’t so easy in some of those costumes!

We didn’t drink that much either. There was something quite restrained about the whole scene, but at the same time, there was in Manchester, and in the other big cities, a really active kind of mainstream gay scene, like the clone scene. The clones were the guys with the mustaches and the check shirts who were very promiscuous, but they were not targets in the way that we were.

[Talking about this] brings back a feeling that I had very strongly at the time, which was not being particularly welcomed in the gay community. I, and people like me, would turn up occasionally at a kind of mainstream gay club and not be admitted. They would say, ‘Oh, you need to go to, say, Dickens [club].’ And I would [ask], ‘Why?’ And they’d say, ‘Because you’re transvestites and that’s where they go.’

I used to have to explain, ‘I’m not dressing as a woman, I’m a boy wearing a wedding dress. I’m perfectly happy as a boy or a man. I’m not trying to look or act like a woman.’ But there was no understanding of any of that. I never got admitted into Hero’s, which was the big gay club in Manchester—the equivalent of say Heaven in New York. I didn’t feel at all understood or supported by the gay community at that time.

Lady Diana, Princess of Wales and Charle

It seems interesting that all this fantasy and dress-up was happening around the same time as the Royal Wedding, with all its pomp and circumstance.

Looking back, it would be easy to say that [there was a connection], but, again, we saw that as being extremely mainstream, and a world that we had difficulty with. The Royal Wedding really meant very little to us.

I can remember looking at it], perhaps arrogantly, and seeing everything that was being done on a kind of commercial level as being so far behind what we were doing. As much as I love and admire Princess Diana, at the time we looked at what she was wearing we could see references to things that we had already done. [Like] when she wore her black velvet knickerbockers; that was something we had done.

So you could see [what we were doing] moving into the commercial arena. Was there ever another time when such a small group of people with no kind of institutional power were actually so influential without wanting to be? Because we didn’t want the mainstream to be, um, latching onto our ideas. And of course once Diana started wearing them, our ideas would then appear in chain stores like Ms. Selfridge, and any person who...had a completely humdrum, normal life would be able to wear that look, and then we didn’t want it anymore.

The Misses Beaton

Listening to you, the Bright Young Things of the 1920s come to mind. They were upper crusty, but were known for making mischief and their shocking behavior.

I’m watching the BBC adaptation of The Pursuit of Love and thinking a lot about the Mitfords and the world of Evelyn Waugh. That was a world of great privilege, and it makes me laugh whenI look through a window into that world. When people in a Mitford novel or a Waugh novel said they had no money, that [meant] they were down to their last, you know, 10,000 in the bank and they still [had] a house in Chelsea.

We really had nothing. I was living on what was known as supplementary benefit, which was 37 pounds, 50 a week. I distinctly remember having a thought one time as I was walking through this grotty area in Hume thinking, I’m happy. I can survive on this.

I got into all the clubs for free. It was enough to have enough money to buy a drink, one drink. We didn’t drink heavily or take drugs; we spent all our money on lining material to make new clothes. And I didn’t eat, so food wasn’t a requirement. We lived on nothing; I mean really um, nothing, at all. So although there’s a parallel , the reality was very different.

The Bright Young Things weren’t an illusion. It really was something that was, what they were; whereas with us, it was all about manufacturing this complete illusion [that] you knew was, was simply that, and everyone else did too.

I guess the escapism of Bright Young Things was very directly related to the horror of the First World War.

There was a fear of war [in the 1980s], too. We forget about it now, but there was a big anxiety around the threat of a nuclear war. I think it’s something that everybody was fearful of, just as people in the 1920s had the shadow of the First World War hanging over them. For us, it was the threat of a nuclear war, and that must have influenced our behavior, too, and it must’ve fed that feeling of not caring about the future.

I can’t help but think what you were doing in the 1980s has some sort of connection to the longstanding British tradition of fancy dress.

I think with hindsight, you’re right. I don’t think any of us at the time would ever have linked what we were doing to any tradition at all. But, looking back, you could say that we were playing with all the tropes of British romantic associations—highwaymen, pirates, dandies…. We were kind of continuing a romantic tradition, I suppose, that began in the 18th or 19th century.

I was looking at a photograph of myself I haven’t published yet, but it’s so similar to that portrait of Lord Byron in Greece, with his head swathed in paisley shawls. I think what we were doing was looking back to a sense of Britishness, but it didn’t occur to us at the time to formulate it as a formal idea.

How did you transition out of club life?

What pushed me back into, if you like, the mainstream was the threat of war. It was early one morning [and] I’d been at an all-night party; you know, that kind of party thing where the last remaining people were just kind of crashed out on the sofa, watching the breakfast television. And [a] headline came up that said that Margaret Thatcher was thinking of introducing conscription for unemployed people to fight in the Balkan’s war, which was raging at the time. That prompted me to think about going back to college and getting myself back into the mainstream because I definitely did not want to be conscripted.

I got myself enrolled back into fashion school, not really knowing where it was going to lead, but just feeling that it was time to climb back into the world again. [I had] a feeling that I couldn’t carry on like this forever, since at some stage, in some kind of way. I was going to have to engage with the establishment.

I went back to Manchester Polytechnic and did my bachelor’s course in fashion, and as a result of that I went to the Royal College.

I’m really so grateful for the situation I found myself in because it was quite unique. It was an experience that has shaped me and my outlook. Having come back into the establishment, if you like, my perspective is always different [than] I think it would have been if I just kind of worked through on a straight channel from when I was at school. There’s a rebellious ... a sense of wanting to look for a different way of doing things, a refusal to always buckle down, a constant search for doing things differently.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Originally Appeared on Vogue