A NJ cold case that's still hot: How the Hall-Mills murders fascinated the nation

"The Trial of the Century."

By definition, unique. A singular sensation. So singular that the 20th century merely had dozens: O.J. Simpson, the Menendez brothers, Amy Fisher and Joey Buttafuoco, JonBenet Ramsey, the Lindbergh kidnapping and many more.

The mother of them all may be the Hall-Mills Murder Case — a juicy tale of lust, homicide and clerical misbehavior that still ranks high in the affection of New Jerseyans.

After all, the bodies were found — exactly 100 years ago Sept. 16 — in a field in Somerset County.

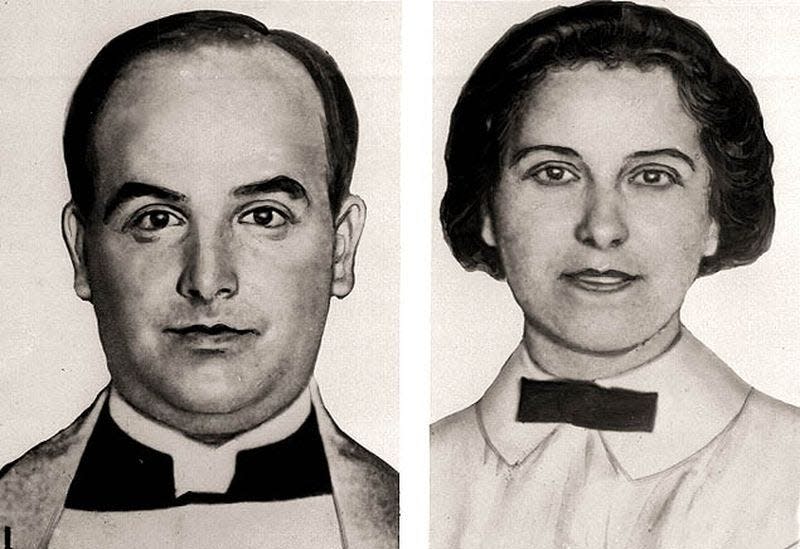

And the church where the two victims — an Episcopal priest and a lady of the choir — indulged in the extramarital carryings-on that seem to have prompted the killing was in New Brunswick.

And, for that matter, still is.

"The church for a long time didn't really want to talk about this, or draw attention to this," said Montclair writer Joe Pompeo.

At the scene

"Blood & Ink: The Scandalous Jazz Age Double Murder that Hooked America on True Crime," which dropped from HarperCollins this week, is not the first book about the sensational episode. But Pompeo, a writer for Vanity Fair, has paid special attention to the role of media in fanning the flames. Hall-Mills might be called the first tabloid trial. Tabloid newspapers had, in fact, only just been invented.

"This was a completely new form of publication that American readers had never seen before," Pompeo said.

More:A 55-year-old murder in Maplewood unsolved? Maybe not anymore

You may, if you're lucky, receive a copy of the book straight from the hands of the author himself. He plans to be manning the merch table for at least one performance of "Thou Shalt Not," a site-specific theater event by the Thinkery & Verse company, running Sept. 15 to Oct. 8, that re-creates the events surrounding the double-murder and its aftermath.

Site-specific — meaning the show will actually be staged in various spaces at the Church of St. John the Evangelist in New Brunswick. The place where the Rev. Edward Wheeler Hall preached, and Eleanor Mills sang. The place where the actual events took place.

Unnerving? You bet.

"We have actors who burn sage before and after every performance," said John Meyer, co-creator of the production with his wife, Karen Alvarado, and several other collaborators.

"We have two actors standing where Eleanor Mills stood every Sunday to sing," Meyer said. "Even if you don't believe in ghosts, it becomes a creepy or even frightening moment."

The church, he says, is a "thin place" — an in-between realm, where past and present, natural and supernatural, meet.

Indeed, that whole part of town is an in-between realm. It still bears the imprint of the forces that led to the appalling episode. "There is still a bit of a class divide in New Brunswick," Meyer said.

Two worlds

Founded in 1861, the church near the corner of George Street and Commercial Avenue (now Paul Robeson Boulevard) marks a boundary.

Up the hill, where the Douglass campus of Rutgers University now sits, were the mansions of the bluebloods — the heirs to the Johnson & Johnson fortune, and the town's first citizens, the wealthy Carpender family. That was where Mrs. Hall — the heiress Frances Noel Stevens Hall — hailed from.

On the other side of the church — then, as now — a sketchier neighborhood begins. Immigrants and the urban poor made up most of its population in the 1920s. This was the home of church members Eleanor Mills and her husband, James.

"The church was where these two worlds collided," Pompeo said. "They mingled as church colleagues, not social equals."

Caught in between, like the church itself, was Edward Wheeler Hall — the young, charismatic new rector of St. John's.

He arrived from Basking Ridge in 1909, middle-class and eager to climb. Frances Stevens, an heiress 7 years older than Hall, and reputedly worth $1.7 million, must have seemed an excellent opportunity.

"They married in 1911, and there was a lot of curiosity about this match," Pompeo said. "There was a fair amount of suspicion he was a gold digger."

Rich wife in the bag, Hall turned his attention to a mistress. Among St. John's congregants, it was an open secret that Hall was dallying with a lady of the choir. Hall and Mills passed letters to each other in hymnals, and otherwise engaged in behavior unbecoming to a man of the cloth and a parishioner — especially given their unequal class status.

"There was a sense of potential clerical grooming and abuse," Meyer said.

The bodies of the pair, apparently dead for 48 hours, were found on Sept. 16, 1922, by a passing couple in a farmer's field just southwest of Buccleuch Park in New Brunswick. There were bullet wounds, a laceration to Eleanor's neck, and tattered love letters lying on the ground nearby.

Hall's wife and brothers were among the key suspects — but a 1922 grand jury investigation yielded no indictments.

And there the sordid matter might have rested, if not for the press.

"It probably would have just gone away, and Frances Hall and her brothers would have lived out their lives in peace, if it were not for Phil Payne's crusade in The Daily Mirror to bring the case back," Pompeo said.

Power of the press

In 1919, The New York Daily News had become America's first tabloid. The New York Graphic and the New York Daily Mirror followed, in 1924.

More:Postcards offer a glimpse into Jersey Shore vacations past

More:In war and peace, these armories in New Jersey are civic treasures

In tandem with their diminished size, these papers had an outsize appetite for sensation. Joseph Medill Patterson, founder of The Daily News, had a very particular notion of all the news that's fit to print.

"Patterson believed there were three things people wanted to read about," Pompeo said. "Love or sex, money, and murder. Readers were especially interested when a story involved all three."

By that standard, Hall-Mills was 11 on a scale of 10. "Certainly, just the notion of a prominent clergyman suddenly being revealed as this philandering guy was absolutely something that would have piqued the interest of readers," Pompeo said.

Back in 1922, the first paper on the scene, The New Brunswick Daily Home News — now Gannett's Home News Tribune — and The New York Times had provided relatively sober coverage. But in subsequent years, the three New York tabloids kept turning up the heat. The Daily News staged a seance, using a fake medium. The Mirror sent its own reporter to New Brunswick, and the writer unearthed new witnesses.

Ultimately, all the newspaper pressure led, in 1926, to a trial. It was a media circus — the biggest until the Lindbergh kidnapping case, 10 years later.

Readers heard all about "The Pig Woman" — the colorful female hog farmer who claimed to have seen the killing. They read about the calling card, with telltale fingerprints, found at the scene of the crime. In an age of fads, of dance marathons and flagpole-sitting, the Hall-Mills case was just what the coroner ordered. Everyone talked about it.

"The 1920s was a singular decade in the country," Pompeo said. "America was emerging from this dark period of war and sickness. This was an era when people wanted to let loose. The press during the 1920s gravitated toward trivialities."

Enduring fascination

For all the heat, there was little new light. The key suspects remained Hall's wife, and several of her relatives — brothers Henry Hewgill Stevens and William Carpender Stevens, and cousin Henry de la Bruyere Carpender. In the end, once again, there were no convictions.

But over the years, the case has been endlessly relitigated by true crime writers and the morbidly curious. The finger has been pointed at Mills' husband, James — a sexton at the church — at the Ku Klux Klan and at sundry other possible culprits. In 1970, there was a third investigation. People still argue about the case online.

As much of a mystery, now, is why the church at the center of the scandal would suddenly embrace a dark episode it had spent 100 years avoiding. This is the second time it has hosted "Thou Shalt Not" — an earlier staged reading was done in 2019.

Meyer, co-author of the play and himself a congregant at the church, has a theory about that.

"My take on it is that for years, the vestry — the democratic body that runs the church — was controlled mostly by men," said Meyer, who in 2020 also created the 20-episode streaming series "That's How the Story Goes: The Hall-Mills Murders Podcast."

In the last 10 years, he said, women have begun to dominate the vestry. And they seem to think a story about a male clergyman abusing his power, and the women who were his victims — not just his murdered mistress, but his cheated-on wife — might be worth talking about.

"The men were discouraged from talking about it for years," Meyer said. "But the women have a completely different view."

"Thou Shalt Not": 8 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, Sept. 15 to Oct. 8. Assembly Hall at the Church of St. John the Evangelist, 189 George St., New Brunswick. $45. eventbrite.com/organizations/events.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Hall-Mills murders: How case galvanized NJ 100 years ago